Future Fund can’t go on forever – it’s time to pay out

Many a conniption was had on this news – that a retired Labor politician would replace a retired Liberal politician to oversee a questionable performing government-owned and operated investment fund – the concern about Combet being that he might nudge Future Fund investment decisions towards areas such as “green energy transition and more affordable housing”.

Notwithstanding Future Fund investment decisions being made by its investment committee, a committee that does not count Future Fund directors as members, the Future Fund chairman and board members have always had the ability to overtly and covertly influence investment decisions. This starts with the committee charter and continues in the hiring of the chief executive and committee members. Personnel is policy, after all.

If there is concern about interference in investment decisions, it remains the prerogative of governments to liquidate the fund – quickly to pay down debt or slowly by requiring it to the pensions for which it was established.

As a bonus, these options would immediately improve the commonwealth budget position absolving the government from the need to break its stage three tax election promise.

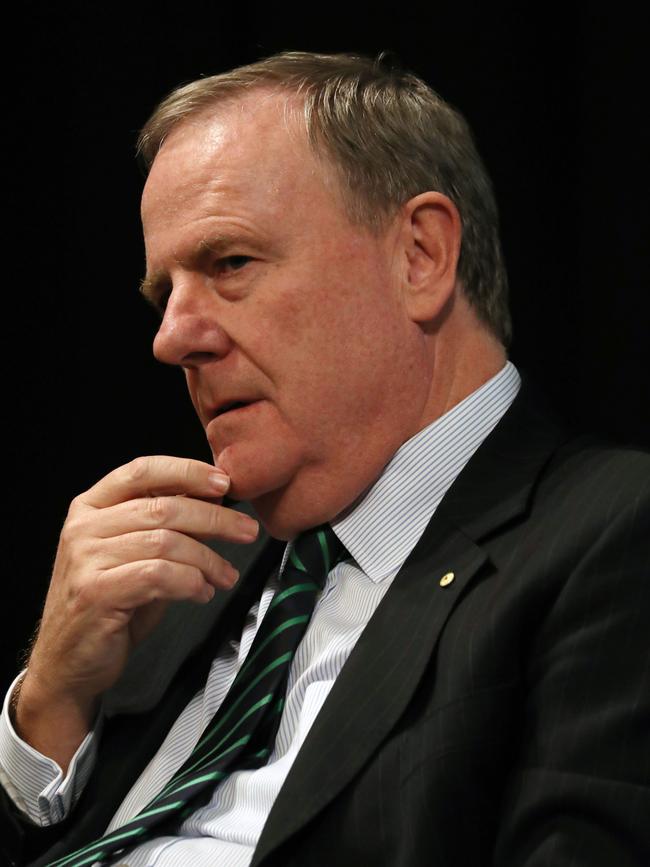

Established in 2006, the Future Fund was to finance the unfunded superannuation liabilities of retired federal public servants. In his second reading speech supporting its establishment, Costello, then federal treasurer, noted that unfunded superannuation liabilities stood at $90bn at June 30, 2005, and were projected to be $140bn by 2020. Costello said: “The Future Fund will be invested with the aim of accumulating financial assets sufficient to offset the government’s unfunded superannuation liabilities by 2020.”

Superannuation liabilities were in fact $276bn at June last year, nearly double the original forecast.

In 2017, distributions were deferred from 2020 to 2026. In October last year, Costello suggested that distribution be deferred further to up to 2046: “At some point in the future, in 10 or 20 years, you could preserve the capital and send the annual earnings back to consolidated revenue to be spent.” This would be a fundamental shift away from the Future Fund’s original purpose to finance unfunded superannuation liabilities.

Today the Future Fund’s portfolio value is $212bn, which comes from a combination of government savings and accumulated earnings. However, irrespective of source, the entirety of the Future Fund’s capital is economically equivalent to borrowings. Money is fungible and given the commonwealth’s nearly $1 trillion of gross debt, $212bn could be otherwise used to pay down debt and significantly reduce interest payments.

The Future Fund is effectively a leveraged investment scheme. If there is an economic shock or market correction, commonwealth debt will retain its value, public servant superannuation liabilities will retain their value, but the value of the Future Fund will likely suffer.

To maintain the Future Fund, federal governments involuntarily co-opt all Australians into this risky investment adventure. No one has yet been asked if they wanted to invest. Granted ordinary superannuation contributions are also non-voluntary, at least decisions on investment strategy and risk appetite are the choice of individuals.

The Future Fund does not afford such luxuries to Australians. Despite also being established to finance unfunded superannuation liabilities, in its 18 years of existence not a single dollar has been distributed for this purpose. Meanwhile, cumulative billions of dollars have flowed from the budget, extracted from the current generation of workers, to finance the retirements of an earlier generation of workers.

As an investment fund in a competitive marketplace, the Future Fund’s performance also needs to be assessed. The Future Fund’s reported 10-year net return was 8.2 per cent. However, because it does not pay tax or incur the exorbitant regulatory compliance borne by ordinary funds, adjustments are necessary to enable comparison. Assuming a 10 per cent correction for these factors implies a comparable return of about 7.5 per cent. Across the same assessment period, regulated (MySuper) products from AustralianSuper generated a net return of 8.6 per cent, HostPlus 8.3 per cent, UniSuper 8.2 per cent and Australian Retirement Trust 8.4 per cent. Evidently, Australians could have received superior returns and earned billions extra had their capital instead been invested with other managers – all without the need to incur the more than $400m of Future Fund annual operating costs.

Recently the Future Fund commissioned Willis Tower Watson to assess the consequence of closing the Future Fund to pay down debt. This analysis concluded that closure would cost taxpayers $200bn across 10 years. Unfortunately, WTW’s analysis drew on problematic assumptions.

WTW projected future annual returns of 9.4 per cent whereas the Future Fund generated, as noted above, a 10-year return of 8.2 per cent to December last year. In October last year Costello also warned that “real returns will continue to be lower than in recent decades”.

Importantly, too, WTW ignored the current obligation of the Future Fund to begin distributions from 2026 – three years into WTW’s 10-year analysis period.

Should the Future Fund, as proposed by Costello, continue to accumulate earnings up to 2046 and not pay pensions, it needs to be asked: for what purpose does the Future Fund exist?

Like many bureaucratic enterprises, there is an unsurprising desire for the Future Fund to have a perpetual existence.

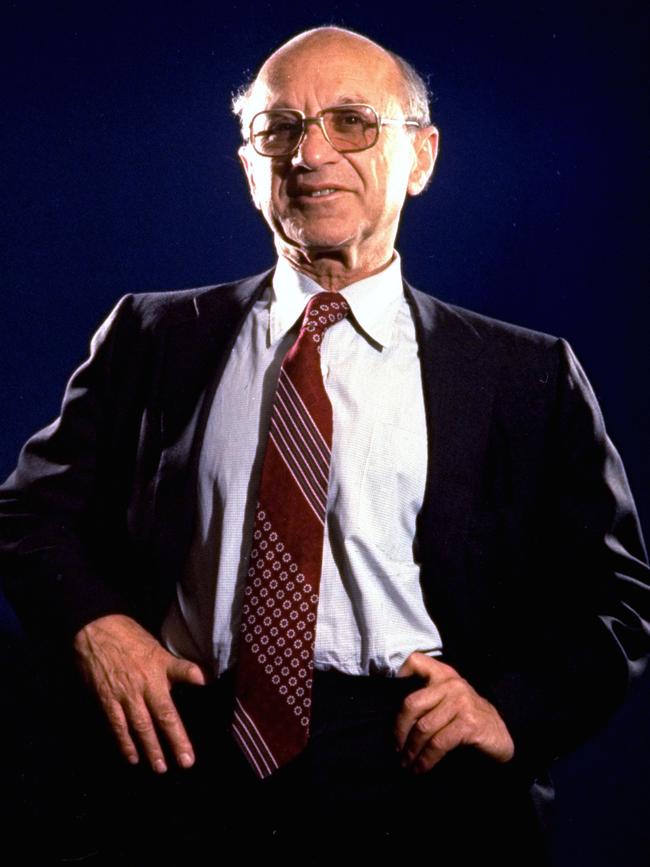

As American economist Milton Friedman observed: “Nothing is so permanent as a temporary government program.” Whether such a perpetual existence is in the interest of Australian taxpayers is another matter.

The Future Fund should start paying pensions or be liquidated to pay down debt.

It was a bright day in January and the clocks were striking 13 when it was announced that Greg Combet would succeed Peter Costello as Future Fund chairman.