Starstruck Chalmers in search of his own narrative on true reform

In a John Curtin Research Centre podcast, Jim Chalmers describes how the subject of his PhD thesis – entitled Brawler Statesman: Paul Keating and Prime Ministerial Leadership in Australia – was inspired by Winston Churchill. “And I felt the same way about Paul,” the Treasurer says. Labor’s task on economic reform, he says, “is to walk further in the same direction”.

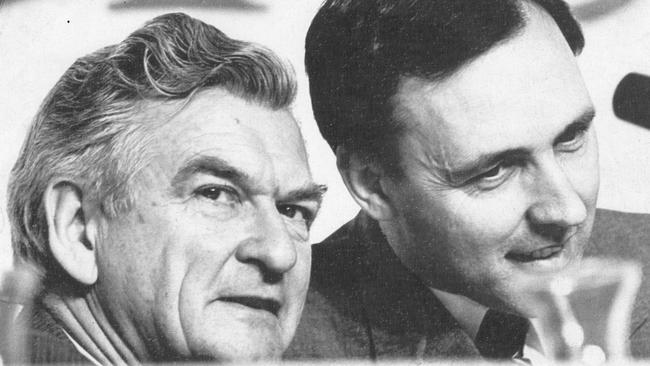

Forty years on from the reforming Hawke-Keating government, Australia faces different circumstances, including energy transformation, which Dr Chalmers says is his obsession and his “reason for being”.

But the nation’s underlying challenges are the same as those of the Hawke-Keating years: improving Australia’s competitiveness through productivity gains to boost living standards. The Albanese government’s overall thrust – a larger government footprint through more interference with markets, more public spending and populist giveaways, more business regulation and a more rigid, union-dominated industrial relations system not linked to productivity gains – are the antithesis, unfortunately, of the Hawke-Keating approach.

Student debt

The Albanese government’s writedown of student debt is a classic example.

As former Treasury assistant secretary David Pearl wrote in December 2024, the 1988 HECS scheme was a signature Hawke-Keating government reform, combining first-rate economic thinking in the pursuit of worthy social democratic goals.

The Albanese government’s debt write-off, in contrast, was yet another instance of its penchant for deeply regressive policy initiatives, Pearl argued.

“The Prime Minister and Treasurer harbour an obsessive hostility towards economic rationalism, which for them is a term of abuse, embodying everything they resent about not only the Liberal Party but also the Hawke-Keating government,” Pearl wrote.

The contradictions in Dr Chalmers’ outlook are as clear now as in January 2023, when his 6000-word essay in The Monthly tried to set out an economic narrative for values-based capitalism.

In a distinct break from the free-market reforms of the Hawke-Keating era, the essay envisaged injecting government further into the economy.

Energy policy

Then, as now, energy was Dr Chalmers’ preoccupation.

But as we said after the essay was published: “It is too early to declare victory on the renewable energy transition given much of it remains on paper rather than in reality. In large measure, the transition has relied on using government intervention and subsidies to make existing technologies more expensive and less efficient so the alternatives appear to represent value.”

A more efficient energy policy, relying less on cost-of-living handouts and more on gas development as a transitional fuel, remains an overarching priority for both major parties.

But in view of other challenges looming large – including the need to lift defence spending by 50 per cent to 3 per cent of GDP and the demands of an ageing population on the health and aged care sectors – the need to re-embrace economic rationalism and a productivity agenda is as pressing now as when Mr Keating warned in 1986 about the danger of Australia becoming “a third-rate economy, a banana republic”.

Taxation reform to encourage enterprise and improve international competitiveness; faster business approvals; encouraging, not deterring, resource developments; and more flexible workplace relations linking productivity gains to improved wages and conditions need to be high on the agenda.

Walk-up call on reform

On the eve of an election campaign that demands both major parties address economic reform – a theme on which Anthony Albanese and Peter Dutton seem to have taken vows of silence – the OECD has given Australia a serious wake-up call.

Fresh OECD data shows no other developed nation has suffered a decline in living standards anywhere near the magnitude of Australia, political editor Simon Benson writes. And no bounce back is coming soon, at least not this decade.

Despite Dr Chalmers’ boast last week about a “soft landing” as national accounts showed a small uptick in growth after seven consecutive negative quarters, the OECD data shows average gains in living standards by member nations of 5.5 per cent since March 2022.

Yet before the national accounts, the cumulative decline in Australian living standards was negative 8.3 per cent. Denmark was the second worst in decline of living standards, at 2.8 per cent, but it hardly came close to Australia.

Even Greece, until recently the basket-case economy of Europe, experienced a rise in living standards of almost 10 per cent.

Dr Chalmers was correct when he told the John Curtin Research Centre “our generational task is to build this new economy in a way that ordinary people in suburbs like the one I grew up in (feel they) are part of the story of churn and change in a positive way. That they are beneficiaries, and not victims, of all of that change.” Their living standards depend on the major parties showing the courage to tackle reform.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout