Scott Morrison’s ministerial self-appointments: a matter of necessity, or a political convenience?

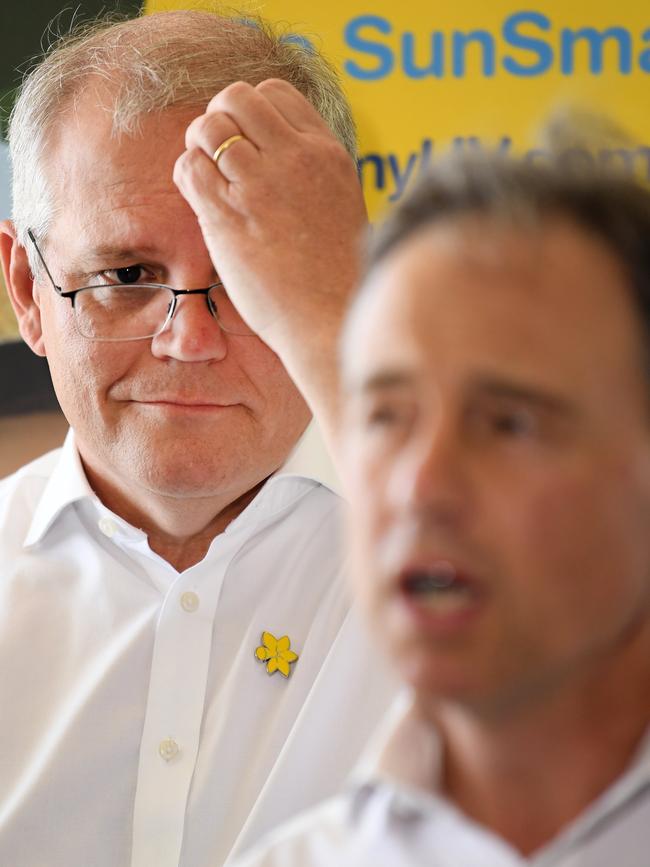

He must explain why he kept the public in the dark and why two of the three ministers concerned at the time – finance minister Mathias Cormann and resources minister Keith Pitt – apparently knew nothing about his action.

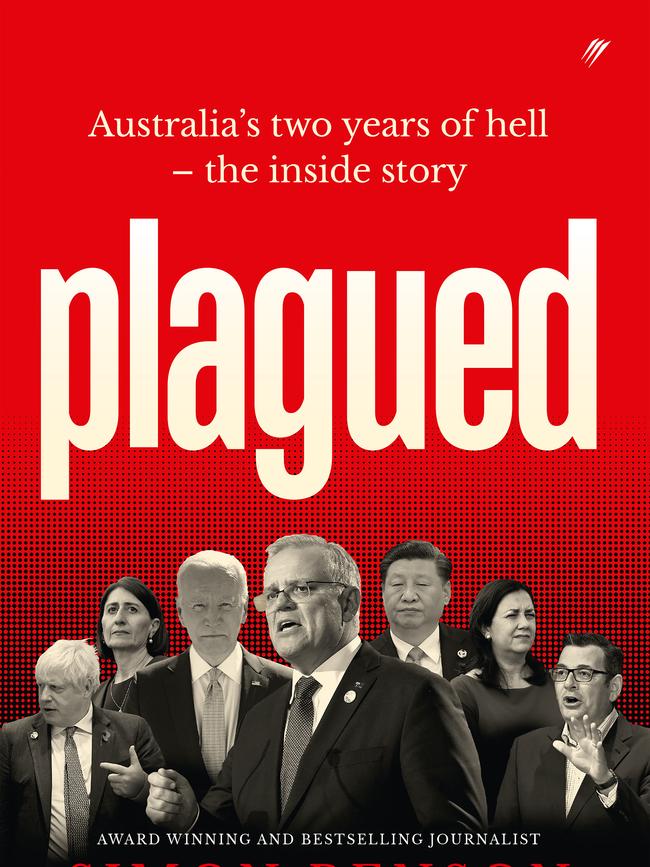

In their new book, Plagued, Simon Benson and Geoff Chambers reveal the health minister at the time, Greg Hunt, approved and welcomed the move. Mr Morrison and Mr Hunt were considering invoking a drastic emergency measure under section 475 of the Biosecurity Act. It effectively would have given Mr Hunt control of the country, with the power to make directives that would override any other law and would not be disallowable by parliament. He had authority to direct any citizen to do, or not do, something to prevent spread of Covid-19.

Mr Morrison, who wanted checks and balances, was advised by attorney-general Christian Porter and had himself sworn in as health minister. The trio saw it as “safeguarding against any one minister having absolute power”.

Mr Morrison also had himself sworn in as finance minister, “to ensure there were two people who had their hands on the purse strings”.

Even amid the Covid crisis, which his government managed better than most across the world, Mr Morrison owed it to voters to explain his extraordinary actions. It was a time, after all, when health officials and state and territory leaders also were taking on unprecedented powers. The pandemic created major demands, requiring leaders to make decisions that were once unimaginable.

Mr Morrison might have more difficulty explaining why he had himself appointed on April 15 last year to take control of the Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources. Was it simply political convenience? If so, it was a disgrace. Eleven months later he scuttled the PEP-11 gas project, 30km off the coast of Newcastle, weeks from the federal election.

Mr Pitt supported the project and had intended to approve it. Much was at stake in the Hunter, where the Coalition government was looking to win and hold seats. The company developing the project, Asset Energy, will lobby Anthony Albanese, who also raised concerns about PEP-11 during the campaign, and NSW Premier Dominic Perrottet to overturn Mr Morrison’s refusal. Asset has pledged to direct all reserves to the domestic market to help address energy shortfalls.

Constitutional lawyers note that Mr Morrison’s decision to swear himself in as a minister of other portfolios was not technically unconstitutional. But it defied custom and practice, undermining transparency and accountability. University of Sydney constitutional law professor Anne Twomey said the move was “presidential”, not done through the usual cabinet process, a key component of the Westminster system.

Governor-General David Hurley said his appointment of Mr Morrison to portfolios other than his own was not “uncommon”. He acted on the advice of the government of the day. Constitutional lawyer Greg Craven said Mr Hurley’s conduct was “beyond reproach”.

The Prime Minister, whose claim that Mr Morrison ran a “shadow government” is potent, has sought the Solicitor-General’s advice. The government, understandably, will milk the issue. But its actions need to be proportionate and avoid becoming mired in a witch-hunt and tied up in the past.

Mr Morrison must tackle the matter. His message on Monday – “Since leaving the job, I haven’t engaged in any day-to-day politics” – will not cut it.

Scott Morrison would do the nation, his own side of politics and his reputation a favour if he answered key questions about why he had himself appointed in secret to the health, finance and resources portfolios during the pandemic.