China’s ‘Wonderful Land’ spin on Uighurs is as authentic as a purple panda

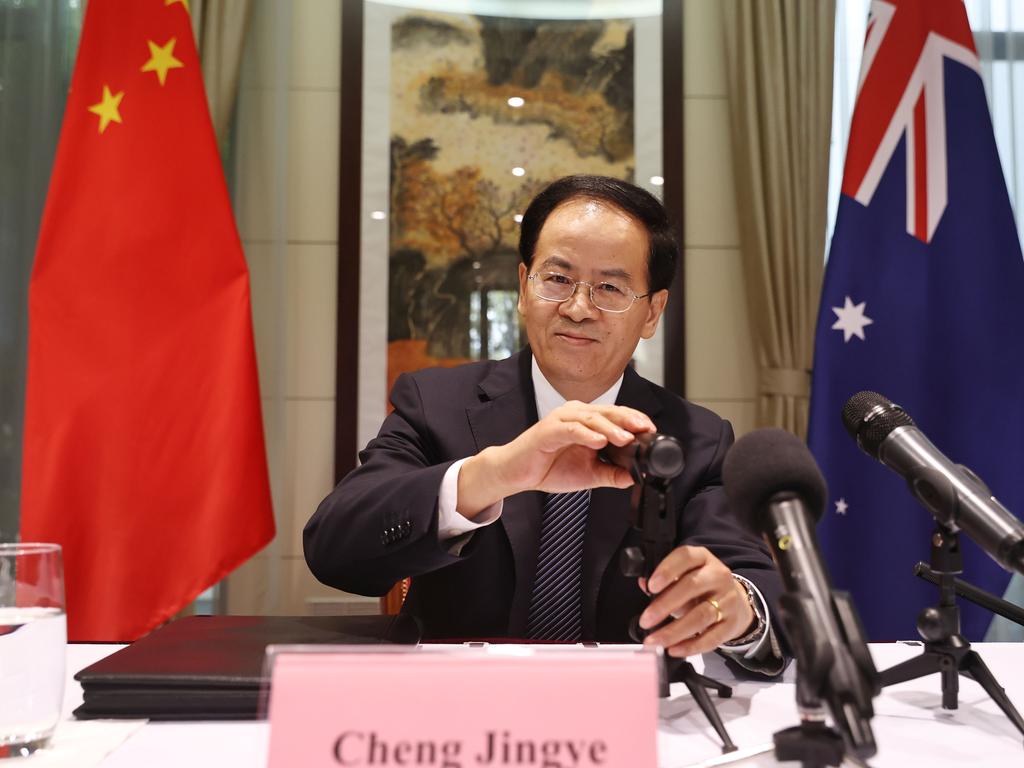

Forget distorted coverage in Western media based on “disinformation”, Chinese ambassador Cheng Jingye insisted. According to the six-minute film, entitled Xinjiang is a Wonderful Land, the Chinese Communist Party has transformed the region, in China’s northwest, in a way that has resulted in “economic development, social stability, livelihood improvement and religious harmony”. Xinjiang is now “a land of life, a land of thriving vitality”.

Across four years, through education and training — no mention of forced imprisonment in re-education camps — the threat of terrorism has been averted. Ethnic groups, living in religious harmony, work “together to develop a vast magnificent part of the motherland”. The Chinese government has put the inheritance, protection and development of the “excellent traditional ethnic cultures of Xinjiang” high on its agenda, journalists were told.

The people shown on camera on Wednesday looked healthy and content in a “promised land of paradise for Muslim Uighurs”, Greg Sheridan writes. Fruit is growing. Chemical production and other industries are flourishing. Transport and infrastructure are being developed. Women shown in the film were dancing happily — no mention of the rapes, forced abortions and sterilisations inflicted on Uighur women reported by the Associated Press in June last year.

Instead of wasting time on amateurish propaganda with the authenticity of a purple panda, China would better serve its interests by working to repair its economic relationship with Australia. It could start by reopening the lines of communication between Chinese Commerce Minister Wang Wentao and Trade Minister Dan Tehan, who remains shut out by his counterpart.

To their credit, Australian producers are defying Chinese trade bans and finding new markets for almost all affected exports, limiting the damage of Beijing’s punitive economic campaign, Ben Packham reports on Thursday. Exports to China are $20bn a year lower after the sanctions. But barley, coal, copper, cotton, sugar and timber producers have partially or completely diverted shipments to new buyers. Wine traders are struggling to make up their loss. But the overall findings will infuriate Beijing.

After watching China’s presentation, Australian Uighur Tangritagh Women’s Association president Ramila Chanisheff said the number of people who had passed through the detention camps could range from five million to eight million, at more than 380 sites across Xinjiang. The press conference, she believes, is a sign of desperation on the part of Beijing, which is “very much afraid” of growing international scrutiny about the province.

The film was staged less than three weeks after the US, Britain, Canada and the EU launched co-ordinated sanctions against Chinese officials over human rights abuses in Xinjiang. In February, Canada’s parliament declared a genocide was under way in the region. Last month, British Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab accused China of a “highly disturbing program of oppression”.

Australia’s approach, at a low point in our bilateral relationship with China, has been more restrained. Foreign Minister Marise Payne has called on China to allow the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights to have access to Xinjiang. Such concerns about the Uighurs, however, are notably absent among Muslim nations, including Iran, which recently signed a 25-year economic and security agreement with China.

Wednesday’s spectacle needs to be understood in the context of Chinese efforts to smother discussion about its serious human rights abuses by playing up the records of other nations, including Australia — sometimes with faux human rights concerns, sometimes by manipulating UN agencies.

“What’s genocide? Massacring native Americans and Aboriginal Australians, forcing people colonised to speak English, French, Spanish, transforming their way of life, these are genocide, right?’’, Hu Xijin, editor of China’s state-affiliated Global Times, tweeted on March 11. In a statement to the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva last month, China accused Australia of violating the human rights of refugees in offshore detention centres.

In Australia, some have been willing to pick up the line. Writing in John Menadue’s journal Pearls and Irritations on March 31, former DFAT officer Alison Broinowski argued human rights were a “glasshouse … stone-throwers beware”.

It is an alarming sign of the times, Glenda Korporaal writes, that Mr Tehan admits he is looking to business to help make the breakthroughs in improving Australia’s strained ties with China. Mr Cheng, regrettably, took as one-eyed a view of the trade bans as he did of life in Xinjiang, blaming Australia for “the difficulties we now have in the bilateral relationship”. Repairing the economic relationship would serve both nations’ interests, as well as regional prosperity and stability. Soviet-style propaganda efforts reminiscent of the Cold War, such as that rolled out on Wednesday, offer nothing constructive.

The video shown to journalists at the Chinese embassy in Canberra on Wednesday was as schmaltzy and picturesque as the opening of The Sound of Music.