Of course, it’s easy to see why Anthony Albanese has made a constitutionally entrenched Indigenous voice to parliament his No.1 priority. Even in the flush of victory, prime ministers are alert to their political mortality and eager to make their mark before their fortunes turn.

And Labor leaders love to be associated with big symbolic changes, especially ones that make it harder for future centre-right governments to get on with implementing their policies.

What’s not to like about this for Labor? It would create a new category of elected activists; it plays to identity politics; it enables the left to claim it’s “on the right side of history”; and it’s a great distraction from the inflation freight train bearing down on the government, its inability to keep its promise about boosting real wages and its likely losing struggle to reduce emissions while keeping the lights on.

If anyone had proposed the insertion of a race-based body into our Constitution even just a decade back, it would have been rejected utterly as a crime against the equal rights and dignity of every human being regardless of colour, culture or gender.

But the long march of the left, and the ascendancy of the cultural Marxists who use climate and identity against liberal institutions, has so enfeebled even parties of the centre right that “show us the detail” is the best they can do in response to this aberration. Whatever happened to Martin Luther King’s ringing declaration that we should be judged by the content of our character rather than the colour of our skin?

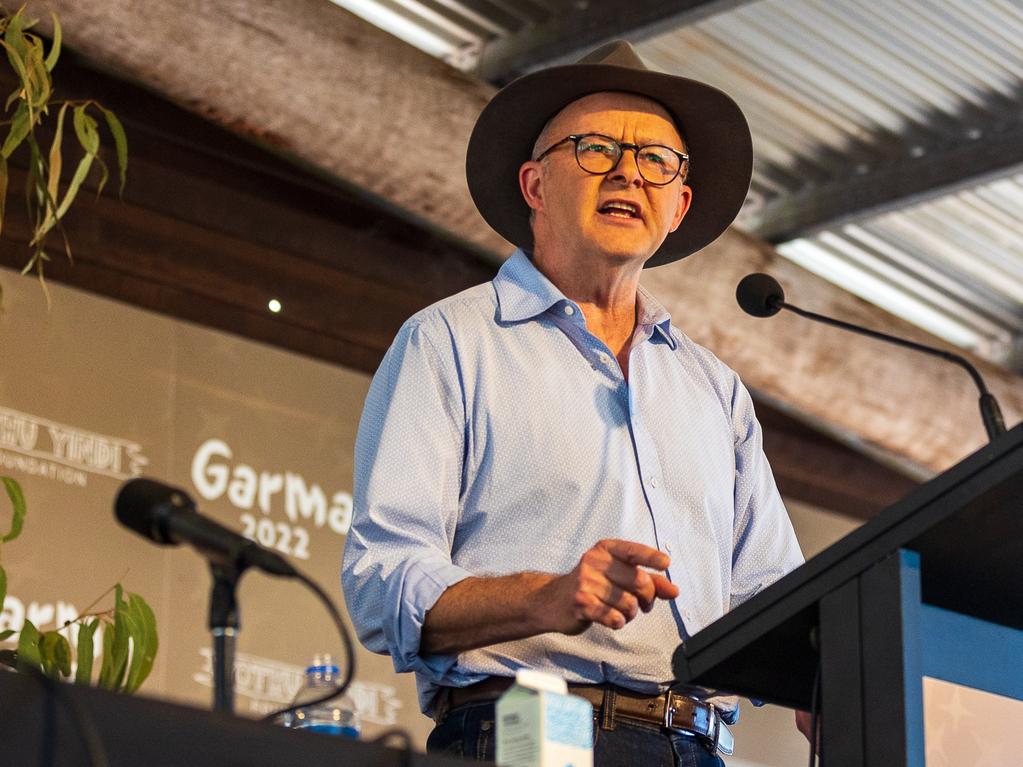

As the Prime Minister confirmed at the Garma Festival in northeast Arnhem Land last weekend, Labor will move in this term of parliament to put a referendum to constitutionally mandate an Indigenous voice to “make representations” to the legislature and to the executive on “matters relating” to Indigenous people.

And, yes, the precise composition and powers of this body would be determined after a successful vote by the parliament itself and could be changed by a subsequent parliament, but it couldn’t be abolished (as the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission once was) and it would indeed be a “brave government”, as Albanese conceded, that ignored it.

In other words, the government’s plan is to create a body of Indigenous Australians, elected by Indigenous Australians, that would have an effective veto over any policy or legislation that affects Indigenous Australians – which could be everything and is likely to be interpreted that way by the High Court. A veritable third chamber of the parliament indeed, with the detail settled by the Labor-Greens majority.

This is the Trojan Horse that the Prime Minister wants us to insert into the Constitution and that the Liberals are equivocating over. It would put into our body politic a new entity that only members of one race can vote for and stand for. It would gum up government because both the legislative and the executive arm would have to take this voice very seriously indeed, as Albanese himself has acknowledged, and as activist courts would insist on, once it’s there in the Constitution, with unspecified authority to make representations about any matters relating to Indigenous people.

And this would just be the start, and could be followed by the other elements of the Uluru Statement from the Heart that launched the voice: namely a “truth-telling” commission and a treaty. A treaty means compensation payments, or reparations, to be paid by taxpayers for decades to come.

Don’t believe it? Ben Wyatt, former West Australian treasurer, talks about a “national compensation fund” and the ABC’s Indigenous affairs editor, Bridget Brennan, says “it has to be about reparations”.

And a “truth-telling” commission here wouldn’t resemble that in post-apartheid South Africa – a chance for people to ventilate race crimes committed against them, in their lifetime – but would involve rewriting our history from the time of settlement into a story of racial exploitation and oppression. If you think the assault on the school curriculum is one-sided now, wait until these new bodies flex their muscles.

These are the further huge challenges the Liberals will face if they leave open the door to a voice.

Labor thinks the voice can be a winner thanks to our collective guilt about what has happened to Aboriginal people in the past and the woke corporate establishment’s readiness to jump on every politically correct bandwagon from footballers wearing pride jerseys to net-zero emissions. And judging by the opposition’s near invisibility on this, some skittish Liberals must already fear that Albanese may be right.

But I would contest that view given what drove majority support for same-sex marriage (namely equality before the law) is what is at risk here by dividing us by race. Before we’re showered in opinion polls to make it all seem inevitable, this will be one of the hardest issues to canvass given people’s fear they will be branded racist for, perversely, defending equality. My sense is that many Australians, in the privacy of the ballot box, would use this vote to send a message to the activist class about an Indigenous voice and much else.

So why the lack of clarity from the opposition? The wonder, given Turnbull’s decisive rejection of the voice, is that the Morrison government dithered about it for so long: resolved not to put it to a referendum that it judged would be soundly defeated, but nonetheless committed to a legislated version of the voice that it never actually got around to doing.

Now, the Coalition has outspoken new senator Jacinta Price, a self-described Warlpiri-Celtic Australian, who calls the voice another “virtue-signalling … gravy train”, plus opposition Indigenous Australians spokesman Julian Leeser, who has long advocated for one.

Surely, the party that first put an Indigenous person, Neville Bonner, into the federal parliament 51 years ago and put the first Indigenous person, Ken Wyatt, into cabinet has a record to be proud of here and shouldn’t feel morally pressured into shrinking from its historic commitment to equality before the law.

Leeser’s quibbling about the voice’s detail while supporting it in principle offends every tenet of liberalism. Peter Dutton needs to be careful lest he’s seen to be missing in action or trying to have an each-way bet on something as important as who we are as a country and how we are governed, especially now that former prime minister Tony Abbott has so firmly declared that the voice has to be opposed. Through his annual trips to the outback, Abbott spent more time coming to understand how remote Aboriginal people live (as opposed to what activists think) than any other prime minister. And he still commands enormous respect from the Liberal base.

It would be a pretty limp opposition that left to minor parties or to people outside the parliament the task of standing up for Australia by fighting this referendum – especially if they manage to win.

Peta Credlin is the host of Credlin on Sky News, 6pm weeknights.

When Malcolm Turnbull, no slouch on legal matters and hardly a constitutional conservative, determined that an Indigenous voice to the parliament amounted to a “third chamber of parliament”, you know it’s a seriously bad idea. It’s wrong in principle; it would be bad in practice; and the only real mystery is why the federal opposition isn’t already opposing it out of hand.