This time the debate is about whether the inclusion of transgender women — those who have gone through puberty as males but who now identify as female — is fair to athletes who are biologically female. The debate is fascinating in how it exposes the philosophical and moral faultlines in our culture, with human rights and transgender advocates on one side and female athletes and their supporters on the other.

Human rights advocates argue that sports are structured around certain core values and beliefs, which include respect, community, professionalism and inclusion.

Australian Sex Discrimination Commissioner Kate Jenkins has said “participation in sport is a human right” and “sport should be a welcoming space that provides empowering experiences for all”.

Push to participate

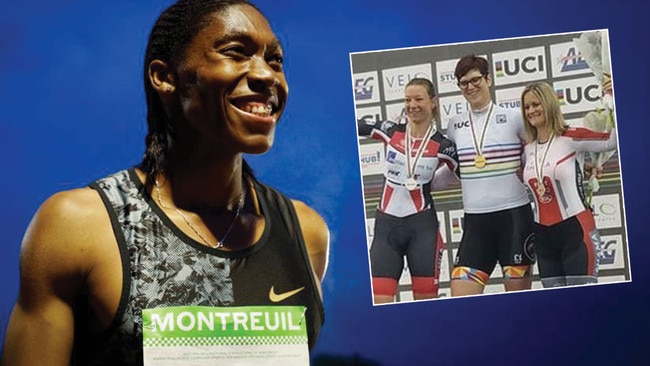

Transgender cyclist Rachel McKinnon has argued that “by preventing trans women from competing or requiring them to take medication, you’re denying their human rights”.

Arguments made by Jenkins and McKinnon continue the tradition of the civil rights movement that expanded equality of opportunity to all. There was once a push to allow women to participate in sports, and now the push is for transgender athletes. Framed in this way, the expansion of rights to trans athletes seems a logical moral imperative.

Yet the arguments from the human rights perspective tend to have a strikingly narrow focus: that of inclusion above all else.

The ethical framework used gives more weight to fostering caring and welcoming environments than to justice, fairness and impartiality. In a culture oriented towards the ethics of care above all else, every individual has a right to a welcoming environment that allows them not only to participate but also to thrive. And the responsibility to provide safe and inclusive environments is doubly important when the group is a vulnerable minority, as transgender people undoubtedly are.

Biological advantage

On the other side of the debate are the female athletes and their supporters who believe athletes who have gone through male puberty have advantages in sports that biological females do not.

These arguments are primarily oriented towards fairness in competition and protecting the integrity of the female division in sports — a division that had to be fought for by women historically and that has existed for only a relatively short time.

The advantages held by athletes who have gone through male puberty are described by tennis legend Martina Navratilova as being “pretty obvious”, but they are worth articulating because they’re not all immediately perceptible to the naked eye. Male physiological advantages in sport include increased muscle mass, higher VO2 max (lung capacity), increased capillarisation (blood flow) and increased bone strength. Importantly, these advantages occur as a result of male puberty and do not disappear during or after gender transition. A recent study looking at the impact of gender transitioning on trans men and trans women found that trans women retained their body strength one year after their gender-affirming treatment.

Another way of considering the advantages of male physiology is to take a broader, statistical perspective. At the Olympic level, the difference between male and female world records hovers around 10 per cent. This remarkable consistency appears across sprinting events, distance events and strength events. In practice, this means that although the number of transgender women competing may be very small, their likelihood of out-competing biological females is very high.

And this is reflected in the discrepancy between notable athletes who are trans men as against those who are trans women. On Wikipedia, 12 notable athletes who are trans men are listed as compared with 34 athletes who are trans women. Trans women are excelling in weightlifting, cycling, mixed martial arts, volleyball, soccer, and track and field.

Last year, eight peak sports bodies including Rugby Australia and Athletics Australia signed on to guidelines that were co-drafted with the Australian Human Rights Commission to “maximise the inclusion” of transgender athletes. These guidelines sit under the 1984 Sex Discrimination Act, which makes it unlawful for a sports body to discriminate against any individual according to their gender identity.

Conflict of care and fair competition

The guidelines are overwhelming oriented towards caring for transgender individuals and providing them with the safest, most inclusive environments possible. The conflict of providing welcoming spaces for all with ensuring fair competition with biological females is mentioned briefly, and largely sidestepped.

Reconciling fairness and inclusion in the context of women’s sports was never going to be easy. But the first step in solving a problem is at least admitting that there is one. By signing on to these guidelines, Australia’s elite sports bodies have signalled that the integrity of the women’s division in sports is a secondary concern.

Another way to manage this conflict would be to restrict the women’s category to athletes who are biologically female and to relabel the men’s division the “open” division, where any and all athletes can compete. Having a female category and an open category that is inclusive of trans, intersex, male and even female athletes would foster real diversity and inclusion while protecting the integrity of women’s sport.

In seeking to reconcile this vexing issue, it’s worth asking why we value sports and why we celebrate sporting achievements in the first place. Is it because we see sport as a vehicle for showcasing diversity and inclusion? Or is it because those who excel in sport do so in competition that is fair?

Claire Lehmann is editor-in-chief of the Quillette platform for free thought.

The debate over who gets to participate in women’s sport is heating up again. Questions over eligibility to compete in female sports bubbled up in 2019 when intersex athlete Caster Semenya was banned from competing by the International Amateur Athletic Federation unless she artificially reduced her testosterone levels.