History is now seminal to the cultural and strategic challenges facing the West. The goal of Marxist, anti-colonial and progressive analysts is to achieve historical justice for victimised minorities by demonstrating the moral failure, past and present, of Western nations.

It is because much historiography is motivated by the politics of the present that it is filled with factual misrepresentation and ideological bias. One of the most prominent authors of the salutary corrective is Nigel Biggar, Professor Emeritus of Moral Theology at the University of Oxford, whose 2023 book, Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning, is an exercise in audacity – a moral judgment on the British Empire and on colonialism generally.

Biggar, an ethicist with a vast grasp of history, is about to visit Australia for a series of speaking engagements. His book covering four centuries of the British Empire from 1550 constitutes a direct challenge to the anti-colonialists and their gospel that colonialism is solely a story of profits, killing and invasion.

Sound familiar?

His scholarship is based not on a defence of empire as such but on a balanced, accurate and fairer reading of history. His targets are unscrupulous history and distorted morality.

“On the colonial front, the politically driven, unhistorical, wholesale denigration of the British Empire not only trashes the record of the West but corrodes faith in it,” Biggar says. Indeed, that is its entire point.

He provides a long list of the “evils” of British colonialism but then provides a long list of its beneficial legacies. He says advocates claiming the evil outweighs the good cannot mount a persuasive case because the bad and the good are so different that they are “incommensurable”. Biggar asks: How many unjustly killed people are worth the blessings of imperially imposed peace?

He knows the stakes are high – nothing less than the moral foundations of our current society. Do we have a civilisation worth supporting or are we doomed to perpetual self-loathing because of irremediable moral flaws? Biggar said the judgment of history goes to “the very integrity of the United Kingdom and the security of the West”, and “that is why I have written this book”.

The issue of slavery is central to the debate. Campaigners from Black Lives Matter to Rhodes Must Fall say white Britons in the third decade of the 21st century are possessed by an anti-black racism derived from the early 18th-century racist slavery.

How valid is this widely accepted proposition?

Biggar says slavery was varied, ancient and universal. It existed in every ancient Mesopotamian civilisation starting with Egypt in the third millennium BC followed by the Greeks, Carthaginians, Romans, Chinese, the Incas and Aztecs, and was practised after Muhammad throughout the Islamic world until around 1920, with the Muslim slave trade out of Africa far exceeding that of European powers across the Atlantic. It was rife in Africa long before European colonisation.

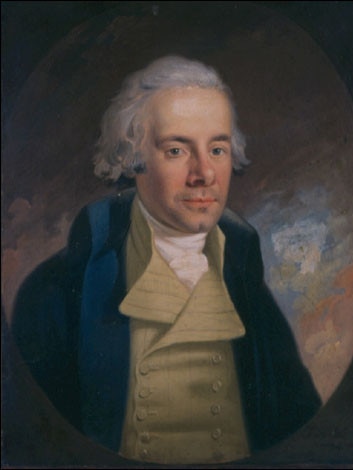

The British were estimated to have shipped 3.3 million slaves from Africa between 1660 and 1807, second behind the Portuguese. After a campaign run by Christian leaders, the efforts of William Wilberforce and agitation inside and outside parliament, the slave trade was abolished in 1807, and in 1834 slaves across the British Empire were formally emancipated.

These events were merely the start of one of the most intense international humanitarian campaigns in history. Partly driven by abolitionist demands in Britain post-1807, Biggar said the imperial government adopted “a permanent policy of trying to suppress both the trade and the institution worldwide”. This involved the creation of a new slave trade department in the Foreign Office to pursue the abolition, Britain’s unsuccessful diplomacy at the Congress of Vienna to secure an abolition treaty with all major European powers, and deployment of Royal Navy ships off the west coast of Africa to disrupt the export of slaves, with the number of ships seldom below 20 during the 1844-65 period and at its height this represented 13 per cent of the navy’s resources

The fleet engaged in confrontation with Brazil, authorised by the parliament, trespassing into Brazilian territorial waters to accost slave ships after which the British attacked Lagos to destroy its slave facilities. Lord Palmerston, twice PM, said the achievement that gave him the greatest pleasure was “forcing the Brazilians to give up their slave trade”.

Biggar said the “humanitarian motive” to suppress slavery was a “common reason” for British imperialism in Africa in the 19th and 20th centuries. Meanwhile in Asia, Sir Stamford Raffles abolished the import of slaves on the island of Penang and then in Java.

Biggar quotes estimates made of the cost of the British suppression campaign on land and sea worldwide over a century and a half, one conclusion being that “the 19th-century costs of suppression were certainly bigger than the 18th-century benefits”. He references the work of Chaim Kaufmann and Robert Pape, who evaluate the total economic cost and conclude that Britain’s effort to suppress the Atlantic slave trade alone was “the most expensive example” of international moral action “recorded in modern history”.

Biggar said the British could not undo the evil of the slave trade but they did the next best thing: they repented of it and liberated the living. But only one side of the history is told today and, to a large extent, that is because the motive is to drive contemporary politics by a misleading historical narrative. The lesson: the only justification for truth-telling is being truthful.

“For the second half of its life, anti-slavery, not slavery, was at the heart of imperial policy,” Biggar wrote. “The vicious racism of slavers and planters was not essential to the British Empire and whatever racism exists in Britain today is not its fruit.”

Yet this is a contentious view because the near exclusively hostile story of Western history holds sway in the media, academia and schools.

Biggar confronts the moral arguments for compensation and reparations for past racism and slavery. Claims to compensation must show continuing loss or harm from past injury, not an easy task over hundreds of years. The 21st-century descendants of these cruelties find their lives owing much to events in the 200 years since their emancipation.

He asks: Can we be sure people would have been better off had their ancestors remained in West Africa? A similar question could be posed in Australia: Can we be sure Indigenous people would have been better off if the British colonisation of Australia had never occurred?

Biggar recounts a conversation between a British diplomat and one of Nigeria’s rulers. The Nigerian was pressing the cause for compensation after Britain’s colonial rule. The diplomat replied: “I entirely agree. And you shall have your compensation – just as soon as we get ours from the Romans.”

As Biggar said, colonisation and empire was the standard form of political organisation for the last 4000 years to 1945. It extended through the Assyrians, Egyptians, Babylonians, Persians, Romans, Ottomans and the Dutch, French and English, among others. Most empires had a positive as well as a negative dimension, though many current histories discount this.

Australia is lucky – its colonialisation by the British meant a generation of British liberals believing in the rights of man and repudiating slavery laid the political foundations for what became one of the world’s early and entrenched democracies. Australia’s colonial experience, reflecting Biggar’s thesis, is a mixture of the good and the bad. We need to hold both truths in our mind and not succumb to polemical narratives of either the all-good or all-bad history.

A relentless feature of public debate is the demonisation of the past – from denigration of the British Empire to the discrediting of Australia’s past as a project in colonialism, racism and violence – a lens used to argue for the nation’s guilt and the case for restitution.