“The priority now is to move away from gas as well,” Friends of the Earth’s Tony Bosworth told the Guardian. Friends of the Earth, like every other international green activist group, also opposes nuclear power. This begs the question: How will Britain keep the lights on without the three sources capable of providing baseload power? Bosworth’s clownish answer is posted on FoE’s website. “We have an abundance of natural resources like wind and solar,” he says. “They’ll go on forever, and we won’t be reliant on expensive gas and oil.”

Climate activists are average people, driven by average calculations of average temperatures on average days projected into the future. On the other hand, people who run electricity systems focus on actual weather since much of the theoretical capacity at their disposal depends on it. So while activists were celebrating their symbolic victory over coal last autumn, energy operators were looking nervously at the long-range weather forecast and the prospect that the weakness of the Polar Vortex might continue into winter. Sure enough, it has, with a characteristic high-pressure system sitting stubbornly over Greenland blocking the Atlantic Gulf Stream winds that make the UK winter less intolerable.

Last week, an Arctic front hit with a vengeance, reducing temperatures to as low as minus-20 and burying parts of England in snow. The diminishing number of Brits who could afford to do so turned up the heating. Many are readers of the Guardian, 85 per cent of whom are in the top socio-economic group. The less affluent readers of the Daily Express were offered helpful tips using a 20m roll of aluminium foil selling for 99p ($1.97) at Aldi. Lining the wall behind the radiator apparently reflects more heat inside.

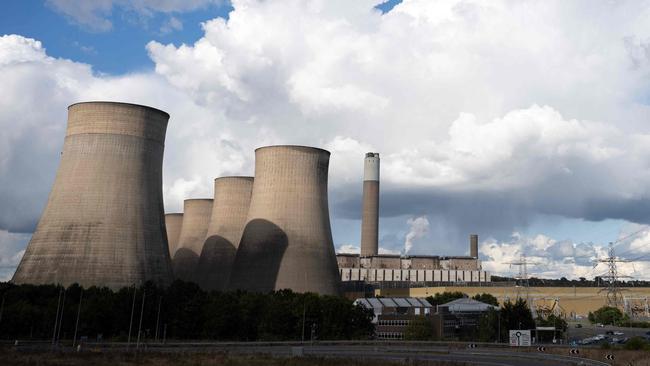

Demand for electricity rose to a high of 50GW on Wednesday, well above the 44.4GW peak predicted by the National Energy System Operator in its winter outlook, published just as 2GW of coal generation capacity from Ratcliffe-on-Soar was vanishing forever. Meanwhile, wind speeds fell, as they often do in winter when the Polar Vortex turns limp. In theory, NESO has 30GW of wind at its disposal. On Wednesday, as electricity demand went through the roof, only 3GW was available. Solar? Forget it, for this is Britain, after all, at the lowest point in the winter solstice.

Where do the system operators turn next after scrounging 4GW of nuclear power from France and Belgium, and 1.5GW of hydro from Norway? They turn to gas, the demon fossil fuel activists want to ban. Between Thursday and Saturday, 55 per cent of electricity came from gas and just 11 per cent from wind and solar. The output from Britain’s nuclear reactors hummed along at 4.7GW, but at 10 per cent of total output it only touches the sides of Britain’s baseload thirst.

At the start of the century, when Britain’s baseload was supplied by coal, the country was blessed with abundant supplies of natural gas. The output from the North Sea fields was around 100 billion cubic metres a year. Output fell dramatically as the fields became depleted. The appetite to invest in new fields was dulled by Boris Johnson’s imposition of a windfall tax on North Sea gas in May 2022, increased to 35 per cent under Rishi Sunak. Output fell to 26 billion cubic metres last year, forcing the UK to import the rest. Subsea pipelines from Norway supplied 29 billion cubic metres while the shortfall was supplied by LNG tankers, mainly from the US and Qatar.

Britain’s gas problems have only just begun. Buying gas on the international spot-market is expensive and supply chains are vulnerable. A 140,000-cubic-metre LNG carrier would supply less than half the daily demand. The tragedy is the UK has abundant reserves of gas, if the green warriors would only call off their campaign. On top of substantial reserves beneath the North Sea, there are at least a quadrillion cubic feet of onshore shale gas that’s hardly been touched. If a tenth of that proves economically viable, Britain would have enough gas to last 50 years.

Yet, as in Australia, the activists have gained the upper hand. A Supreme Court decision in June known as the Finch ruling obliges planning officials to factor in the emissions of consumers, not just the emissions used in extraction and transportation. This has set the scene for a judicial activists’ picnic. Greenpeace and Uplift have applied for a judicial review of the Rosebank and Jackdaw North Sea developments sending them back to the planning stage.

It’s a flashback to the nightmare of Britain in the 1970s when a miners strike put the country on a three-day week and the BBC shut down at 10.30pm to save electricity. This time, it’s not the union movement that’s usurping the role of an elected government but the green movement, aided and abetted by the courts.

There are lessons for Australia from this gloomy winter’s tale. The nuclear debate has taken attention from our immediate challenge: the critical gas shortage created in large part by the same climate zealotry. Yet gas will be an indispensable part of our energy mix well into the second half of the century, with or without nuclear. It is vital even to Chris Bowen’s plan, which accepts the intermittent challenge can’t be overcome with batteries and pumped hydro alone.

Reducing a continent as richly endowed as ours to the point where it is about to import gas on the east coast is no mean feat. It has taken many years of patient activism, weak-kneed government, pusillanimous journalism and dumbed-down policy discussion to get us to this point. Here, as in Britain, it will take years to reverse the momentum and establish a reliable energy network if we ever do, which for the moment is an open question.

Nick Cater is senior fellow at Menzies Research Centre.

Britain’s last coal-fired power station closed at the end of September, throwing households to the mercy of the weather. Turbines and cooling towers at Ratcliffe-on-Soar in Nottinghamshire are about to be demolished to make way for a zero-carbon technology and energy hub. Sadly, Britain’s green activists have no plans to follow coal into retirement. The curse, or joy, of being a fighter for progressive causes is that your work is never done.