China’s rhetoric has changed but not its plan to dominate

That’s why there was such palpable relief when Beijing recently took us out of a long diplomatic deep freeze, with a six-year gap between leaders’ meetings, that started when we banned Huawei from the 5G network, deepened when Chinese infrastructure investments were blocked and reached its nadir after Australia called for a full independent investigation into the Wuhan virus.

But despite President Xi Jinping’s emollient words, thus far at least there has been no lift in the trade boycotts and no sign that hostage Australian journalist Cheng Lei will be released.

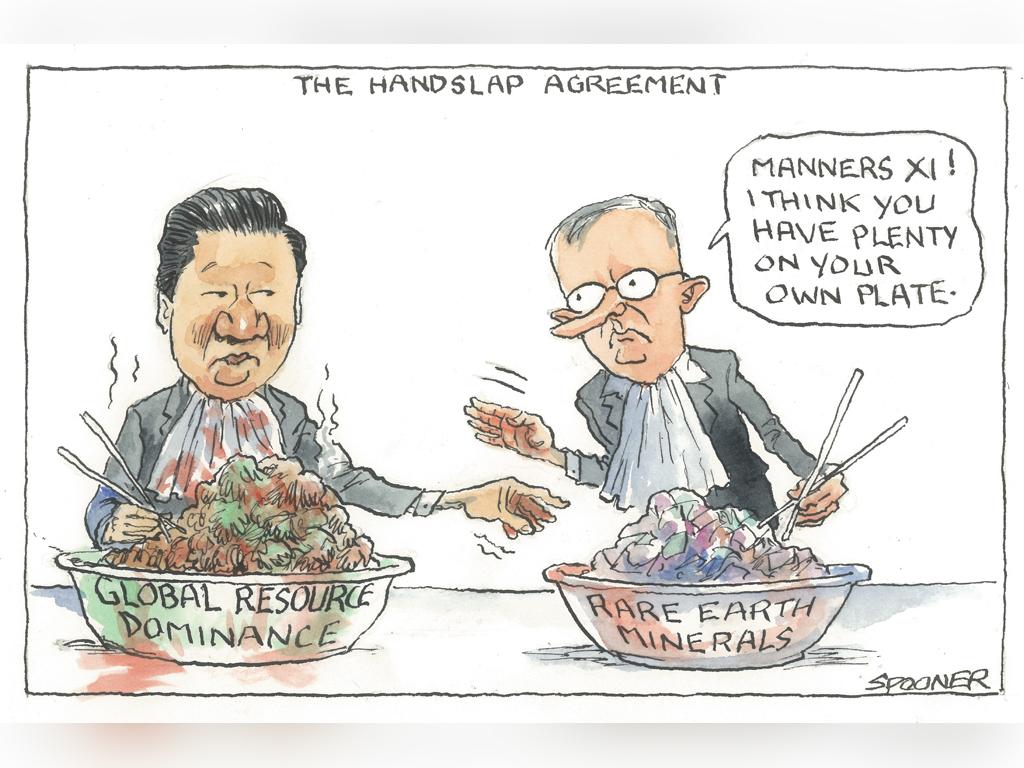

The risk is that we will think Beijing has changed, just because the language is softer and official outlets no longer refer to us as chewing gum on China’s boot. But it hasn’t. Marxism-Leninism is still reinforcing Middle Kingdom exceptionalism, Beijing still aims to be the world’s dominant power by mid-century and the People’s Liberation Army is still daily probing Taiwan’s defences looking for signs of weakness.

Even though Beijing’s military planners may have revised their timetables in the light of Ukraine stopping the Russian steamroller, they still want to be in a position to destroy US power in the Western Pacific and to seize their “rebel province” as soon as possible, if they can’t already. And bad though Vladimir Putin’s war on Ukraine has been, Xi’s long-threatened war on Taiwan would be worse, far worse – and not just for its regional neighbours but for the whole world.

Putin’s Ukraine war challenges our values. Any Xi-instigated war over Taiwan would threaten our interests, too. And not just those of the US and its allies in the Western Pacific but those of the 100-plus countries with China as their biggest trading partner. Whatever stance they took on the rights and wrongs of the conflict, and whether or not they imposed sanctions on the aggressor, there would be no shipping, no flights and virtually no trade because even the imminent threat of war, let alone any fighting, would stop it dead.

This might make war unthinkable but it certainly doesn’t make it impossible, especially to a regime that doesn’t need to win elections and that figures its people are more capable of absorbing pain than the citizens of effete and decadent democracies in decline.

Let’s be clear about the choices here. Helping Taiwan risks a wider war as China blockades air and sea routes of resupply. Not helping Taiwan guarantees the collapse of the US alliance system as America abandons a friend in need, and that spells the end of the postwar liberal order that has produced more freedom, more safety and more prosperity than mankind has known before

Any pause to reflect in Beijing that Putin’s misjudged war may have created is useful only if Taiwan and its friends use it just as judiciously – to prepare for the worst as well as simply to hope for the best.

For Taiwan, this should mean hardening its infrastructure, shielding its military assets, learning how to “swarm” an invasion fleet, trying to acquire an Iron Dome-style missile shield and, to change Beijing’s calculus, trying to acquire the capacity to strike back hard. And to manage this escalating preparedness without driving its own citizens to conclude that freedom is not worth the fight.

For the other Western Pacific democracies it should mean more rapid acquisition of defensive and offensive missile systems, more developed defensive and offensive cyber capability, plus rapid planning for the economic resilience needed to cope, not only with the cessation of trade but also with the impact on production of the loss of Chinese intermediate goods from every critical supply chain. Some would argue this interdependency of China and the world makes conflict impossible, but I doubt that’s the view from Beijing, where trade and investment are seen as strategy by other means.

There’s no doubt Australian attitudes to Beijing have rapidly hardened since 2014, when Xi’s declaration to our parliament that China would be “fully democratic by mid century” perhaps marked the high tide of the global wishful thinking about China – that some economic freedom would inevitably bring political freedom in its wake.

Far more Australians now see China as a threat than an opportunity; and from diversifying trade to reducing universities’ dependence on Chinese students, making more of an effort to reassure people of Chinese background that they belong in Team Australia, acquiring a nuclear-powered submarine deterrent, and lifting military spending towards 3 per cent of gross domestic product, there’s a broad bipartisan consensus – yet none of this is happening nearly quickly enough. For the best part of 40 years the world avoided the twin evils of nuclear war, on the one hand, and the dominance of totalitarian communism on the other, essentially because the US was prepared to “pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, (and) oppose any foe to assure the survival and the success of liberty”, in John F. Kennedy’s words. The old Soviet Union understood there were some red lines that simply weren’t worth crossing.

This new cold war will be different; for one thing, as a first-rate economy, now with the military power to match, China is probably a more formidable competitor than the old Soviet Union ever was. But it will take much the same alliance system, with much the same clear red lines, to gain much the same outcome: an uneasy peace until the inherent contradictions of communism eventually produce some sort of regime change.

If Ukraine with 40 million people needs NATO’s support to resist a nuclear-armed Russia with 140 million, how much more do Taiwan’s 25 million need outside help to maintain their freedom from 1.4 billion Chinese?

Because what hope can there be in a world where the strong do what they will and the weak suffer what they must? As Edmund Burke once observed, “When bad men combine, the good must associate else they will fall, one by one, an unpitied sacrifice in a contemptible struggle.”

By unambiguously stating on four separate occasions that America would definitely fight for Taiwan, even if officials then walked back what he meant, President Joe Biden might have managed to maintain the policy of strategic ambiguity while muscling up its content.

An important factor in persuading Beijing that it could confront a powerful alliance rather than a rebel province was the statement by the late former Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe that “a Taiwan emergency is a Japanese emergency and therefore an emergency for the Japan-US alliance”. Another is the emergence of the Quad, a strong partnership of liberal, pluralist democracies.

But it’s one thing to be ready to fight; it’s another to be able to win, or at least to be confident that no rational adversary would dare to risk a war. All history teaches what the Ukraine experience confirms: that weakness invites aggression.

We have to ensure our passion for peace never becomes peace at any price, which is neither prudent nor moral but a weak surrender to evil.

This is an edited extract of a speech former prime minister Tony Abbott made to the Danube Institute in Budapest on December 2.

Other than Taiwan itself, the US, and perhaps Japan, no country on earth has a greater interest than Australia in preventing war across the Taiwan Strait. Not only would it jeopardise the 35 per cent of our trade that goes to China, and the 60 per cent that goes to East Asia, but it would expose the American bases here to direct attack if the US joined in.