Dennis Shanahan reported in The Australian on Wednesday that the “Albanese government is considering ways to limit China’s investment and influence” in the $20bn critical minerals industry.

Reshaping the national approach to foreign direct investment from China is overdue. Recent Coalition governments have made a string of ad-hoc decisions, some preventing Chinese investments into critical infrastructure but overlooking others.

Malcolm Turnbull and Scott Morrison both came to realise that investments from Chinese state-owned and so-called private business entities were dangerous. These companies had no control over the influence of the Communist Party and the power of China’s massive intelligence apparatus using business as a cover for spying and cyber interference.

But Treasury’s ideological convictions run deep. For years (and maybe still), the Foreign Investment Review Board held hard to the view that there was nothing about China that added more risk to investments. As late as August 2019, the FIRB chairman at the time, David Irvine, told a conference Australia “would welcome the opportunity to work with Chinese investors, including investment on critical infrastructure”.

FIRB delighted in having the “most liberal foreign investment regime in our region”. Australia was accepting Chinese investment into areas such as gas, the electricity grid, ports, airports, critical commodities and huge areas of farmland. Australians could not invest in Chinese critical infrastructure, but that didn’t matter, Irvine explained, because “our policies were not framed in the context of reciprocity but of national interest”.

Irvine was a professional friend and a fine Australian, but we agreed to differ over foreign direct investment from China. In my view it was never in Australia’s interest to deepen our economic dependency on Beijing. Slowly, and with infinite reluctance, Australian governments talked themselves out of an infatuation with Chinese capital. That journey started with an idiotic Defence lapse in 2015 that saw (and still claims to see) nothing wrong in leasing the Port of Darwin to a Chinese company for 99 years.

In 2016, Morrison as treasurer prevented a lease of the majority of Ausgrid, the company providing NSW’s electricity distribution network, to a Chinese state-owned enterprise or a Hong Kong company.

In 2018, Turnbull’s last decision as prime minister was to exclude Huawei and other Chinese companies from the 5G network.

Turnbull was no anti-China hawk early in his prime ministership. He demanded that the Australian intelligence community prove to him why the risk of Chinese cyber intrusion into 5G couldn’t be mitigated.

To their great credit, the Australian Signals Directorate did precisely that. One of ASD’s architects of the 5G outcome explained: “If your telcos have a 5G operation and maintenance contract with a company beholden to the intelligence agencies of a foreign state, and that state does not share your interests, you need to consider the risk that you are paying a fox to babysit your chickens.”

Turnbull’s 5G decision redefined Australia’s relationship with Beijing. The arrival of Covid-19 then created an opportunity to partially close the doors on Chinese FDI by lowering to zero dollars the value of investments FIRB would review for national security concerns. This was the right policy decision but governments have not explained the risks presented by an aggressive China or the limited steps taken to strengthen the country.

A senior Morrison staffer put it to me in 2020 that a day that passed without mentioning China was a day we could sell Beijing more coal and iron ore. But policy that isn’t explained or defended is a weak platform on which to build national security foundations.

Instead, prime ministers and ministers have talked in code about the solemn responsibilities of governments to protect national security. Last week Jim Chalmers followed this path at The Australian’s Critical Minerals Summit: “As investment interest grows and as the sources of that investment interest grow, we’ll need to be more assertive about encouraging investment that clearly aligns with our national interest.”

Rest assured that the Treasurer is not worried about FDI from Canada, Chile, Costa Rica or even – if any investment dollars could be sourced there – Cuba. Only one country presents a sustained and growing threat to Australian security: China.

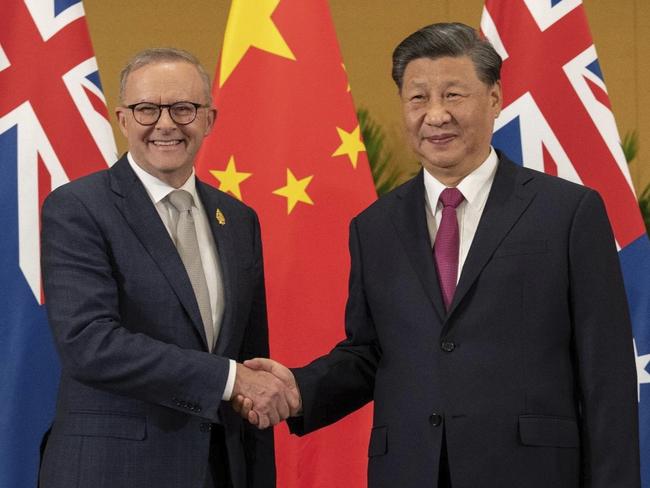

For Anthony Albanese, a decision to exclude Chinese FDI from rare earths and critical minerals extraction and processing would be a leadership-defining “5G moment”. Beijing is just as determined to be the dominant global controller of rare earth and critical mineral commodities and finished materials as it wanted to be the global master of 5G.

As with 5G, Beijing will have serious concerns about Australia’s approach to critical minerals. It will worry that Australian policy decisions will be followed by other countries, although on this occasion even cautious Canada is ahead of us in ordering Chinese companies this month to divest from three mining ventures.

Critical minerals are essential components in defence technology for sensors and weapons guidance, in advanced computing to support artificial intelligence and to support industrial decarbonisation. Beijing wants to assure its own supplies of these materials and, to the extent it can, make other countries dependent on its supply of processed materials.

China will do its utmost to keep Australia at the bottom end of the critical materials value chain – that is extraction rather refining – because refining offers a pathway to more self-reliance with our allies.

We should not get too far ahead of Labor’s apparent “consideration” of how to protect critical minerals.

At the beginning of November, Resources Minister Madeleine King appeared to have no concerns about a deal to export rare earth from a Victorian mine to a Chinese company.

On November 21, current FIRB chairman Bruce Miller speculated that the Albanese-Xi Jinping meeting would lead to more Chinese investment applications. He told The Australian Financial Review: “We are stabilising the bilateral relationship and hopefully we can resume – you know – a normal sort of relationship.”

Nothing has changed in Xi’s ambition to make China the dominant power in the Indo-Pacific. This will narrow Australia’s strategic options regardless of whether leaders meet. The challenge for the Prime Minister is to decide between two competing lines.

There is the fiction that relations with China have stabilised, in which case FIRB will rejoice at new investment.

Or there is the harder reality that, in the interests of national security, we need to walk away from Xi’s desire to control Australia’s critical minerals industry. Delivering that outcome will call for a measure of strategic grit not yet seen from this government.

A Labor plan to become “more assertive” in protecting the national interest on foreign investment decisions would be truly good news for Australia.