“Have you seen what happens to people in this job?” Anthony Albanese replied. “You’ve got to have some discipline. You’ve got to have some rules.”

The exchange offered an insight into the complex character of the Prime Minister. His resistance to tempting bakery products is not matched by his resistance to special pleading from vested interests such as the United Workers Union, whose campaign for better pay for childcare workers has secured a $3.6bn commitment from Albanese’s government.

Won’t that be inflationary? Peter Stefanovic asked when Albanese appeared on Sky News to spruik the deal. “No,” he replied. “Because what it will do is keep costs down, importantly.” Stefanovic persisted, citing Reserve Bank governor Michele Bullock’s concern that government spending is feeding inflation. “Yeah, that’s very different,” Albanese replied.

It turned out not to be very different after all. Break open one bread roll and before you know it everyone wants a slice. Albanese’s generosity to childcare workers prompted a demand for a similar deal from the Australian Services Union on behalf of 300,000 disability workers.

This is how inflationary wage spirals start and why decisions on public service wages are best left to tribunals, rather than stitched up in piecemeal deals between Labor prime ministers and unions.

Setting aside the questionable proposition that governments can stop the march of inflation by throwing money in its path, the ever-growing government spending on childcare raises far more important family policy questions that few are game to ask.

Is it sensible, for instance, to skew assistance in favour of working couples and away from single-income families? Is it fair that working couples with one child in care received an average subsidy of $8181 last year while the 30 per cent of mothers or fathers who chose to stay at home received nothing?

The growth in federal government spending on childcare took off under Julia Gillard’s government, driven by an enticing narrative about breaking glass ceilings buttressed with the superficially respectable economic argument that greater workforce participation boosted productivity and economic growth.

It does not. That’s because outsourcing household responsibilities does not create fresh economic activity. It simply brings it on to the books.

The most contentious argument in favour of professional childcare was that it was in the best interests of the child. Albanese persisted with this flawed line of reasoning in his round of radio and television interviews at the end of last week.

“Of course it’s good for kids,” he told Triple M Perth. “Ninety per cent of human brain development occurs in the first five years.”

Many experts in early childhood development would draw the opposite conclusion based on the salient fact that time spent building a stable, bonded relationship with their children is the best investment in a child’s future that parents can make.

In her 2017 book, Being There, US psychoanalyst Erica Komisar assembles a convincing body of evidence to show that excessively long periods spent in an institutional setting is, to put it mildly, a subprime option.

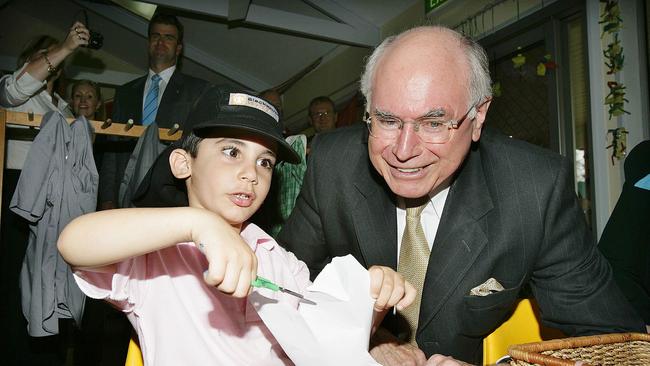

Yet childcare is more than just childminding, Albanese told listeners to 6PR on Friday. He cited the evidence of his own eyes, gathered during a fleeting visit to a childcare centre in the Perth suburb of Dayton. “There they were learning about the letter ‘L’ and the letter ‘U’, with a whole lot of little blocks about how to do that,” Albanese said.

The idea that preschool children must be institutionalised to learn the alphabet is an insult to generations of conscientious parents. An Australian Institute of Health and Welfare survey in 2017 found 79 per cent of children aged 0 to two years had been read or told stories by a parent on three or more days in the previous week, while 44 per cent of them had libraries of between 25 and 100 children’s books in their home.

Institutional early learning can accelerate the development of children from bookless backgrounds with inattentive parents, but children from low socio-economic groups and non-English-speaking homes are less likely to be at childcare centres, which draw their clients disproportionably from English-speaking, educated, professional homes.

The result of increased federal government funding has been a substantial migration of children from so-called informal care, most commonly grandparents, to professional care. While informal care halved between 1999 and 2017, professional care increased by around 70 per cent. Transferring familial obligations to the state and robbing children of the benefits of forming bonds with their grandparents is the unintended consequence of government interference in the market.

Sadly, a Labor government is probably incapable of fixing this expensive policy mess, just as it is incapable of fixing the National Disability Insurance Scheme where costs will blow out even further when the government caves in to the latest pay demand. It will fall to the next Coalition government to restore sanity to family policy. It will be a delicate conversation. Nothing will be gained by making parents feel more uncomfortable about the conflict between their twin responsibilities as parents and breadwinners.

Childcare centres provide an invaluable service and must be supported by government since an under-resourced, unregulated sector would be far worse. The dedication of childcare professionals must be encouraged and rewarded since, like good teachers, they are the hope of the side.

The Coalition might start by revisiting the intention behind Family Tax Benefit Part B, John Howard’s solution to the challenge of assisting parents without discriminating against those who chose not to work. It might seek to balance the level of subsidies with out-of-pocket costs for parents to ensure full-time parents were no worse off. It might consider family-friendly reforms to the tax system, including incentives to increase the birthrate. Australia is not the only country that has tried to kick this can down the road by encouraging migration. Yet, as we are beginning to learn, there are undesirable consequences to that approach – even in a well-adjusted country such as Australia.

Reforming family policy, with its entrenched subsidies and vested commercial interests, will be among the most difficult challenges faced by an incoming Coalition government. It will require the investment of substantial political capital. Yet for a party focused on the long-term interests of Australia, as a nation of well-balanced individuals living where possible in stable family units, there is surely nothing more important.

Nick Cater is a senior fellow at Menzies Research Centre.

“Come on, mate,” responded Nova’s Nathan Morris. “You can go and have a crusty roll here and there, can’t you?”