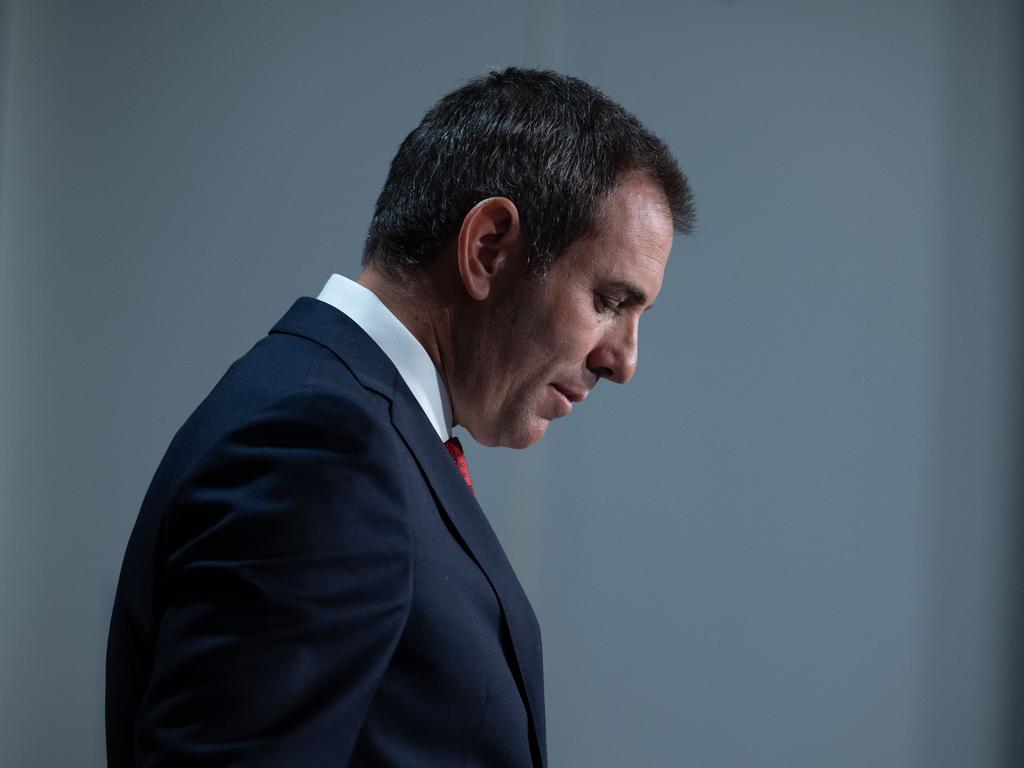

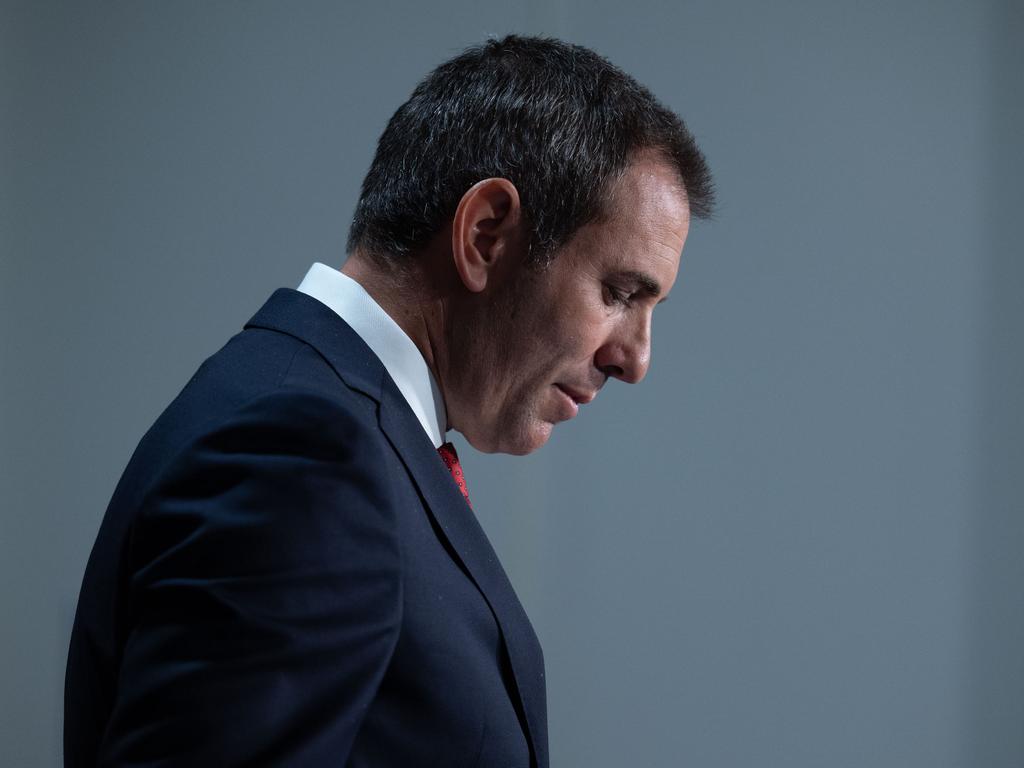

Chalmers rhetoric lost in policy vacuum

But this is the age of yoga mats and chai lattes, wellbeing indices and teal voters. Replete with good feelings, Treasurer Jim Chalmers’s essay exudes the spirit of the times, in which Australia’s most affluent constituencies are greener than green while the top end of town is more profoundly anguished by gender equity than by the return on equity.

Chalmers’s method is simplicity itself. It consists of caricaturing his opponents, assaulting straw men, ignoring all contrary evidence, and then failing to explain his own philosophy with any clarity or detail.

No facts are presented, no terms defined, no phrase dear to “Davos man” left unsaid. On reading it carefully, the ghastly thought arises that Jacinda Ardern has been teleported across the Tasman and reincarnated as Australia’s Treasurer. And as with “Ardern speak” – or, for that matter, texts generated by ChatGPT – it obfuscates and elides more often than it elucidates and clarifies. We are repeatedly told, for example, businesses should be “values-based”; what we are not told is what that would actually entail. Nor is that unimportant: call me cold-hearted, but I would prefer it if Qantas would focus on delivering my luggage rather than on delivering my ethics.

Equally, despite its length, none of the tough questions the government needs to answer are tackled. It is, to take just one example, commendable that Chalmers worries about our productivity slowdown. But given that the collapse in the construction industry’s productivity accounts for a very large share of the decline, it would be even more commendable if he explained how letting the building unions run rampant will help turn the situation around.

Yet at least some of the thoughts lurking beneath the verbiage are not as appalling as Chalmers’s critics have suggested.

After all, the idea of designing markets for government services, and harnessing charities and businesses to assist in their provision, is hardly new: it was first forcibly advanced by the so-called Tory rebels of 1958, namely Enoch Powell, Peter Thorneycroft and Nigel Birch – that is, by the odious “neo-liberals” Chalmers excoriates.

Nor is it inherently objectionable: on the contrary, if the disciplines of private investors and of competitive markets can be usefully brought to bear on the supply of government services and the achievement of government objectives, it would surely be to the good.

However, what the essay lacks is any acknowledgment of the challenges that involves. Nothing better highlights those challenges than the market design disasters of the Rudd-Gillard-Rudd years: the tragedy of the home insulation scheme; the deeply flawed vocational education and training “Fee Help” program, which cost more than $3bn to clean up; and the spectacularly ill-designed and poorly implemented National Disability Insurance Scheme.

What those experiences – and that of Chalmers’s own gas code – highlight is the fundamental difficulty government-designed markets encounter.

Private markets, for all of their weaknesses, have the incentive and capacity to self-correct: when their design is poor, the flaws trigger changes in market structure and conduct that usually ameliorate the problems.

But poorly designed government markets don’t adjust automatically, not least because their parameters are typically locked in by legislation. Indeed, by creating profit opportunities, the distortions in their design attract providers whose interests lie in perpetuating the easy pickings, spawning pressure groups that stymie corrective efforts – with the result that the costs the programs impose continue to mount.

Those realities are ignored by Chalmers: the failings of markets worry him; the failings of government do not. Instead, one catches time and again the familiar accent of the reformer armed with an infallible plan for circumventing the obstacles raised by human folly and perversity.

Unfortunately, public policy is not a romantic symphony of purpose and ideal. Dealing with that fact requires imposing clear limiting principles on the scope and substance of government intervention. In contrast, setting undefinable goals, such as promoting “wellbeing”, undermines policy focus, blurs accountability and invites unbounded, ultimately ineffectual, meddling: to aim at everything is to not aim at all.

Our current predicaments make the need for limiting principles all the greater. Chalmers exaggerates wildly in describing the Coalition government as a “wasted decade”. But even putting aside the woefully botched “energy transition”, it is undeniable that severe weaknesses were allowed to accumulate.

Commonwealth spending on education, for example, increased by more than 60 per cent in real terms; yet our schools’ performance deteriorated. Equally, public expenditure on hospitals increased by nearly 70 per cent; but that couldn’t avert lengthy queues at emergency departments or prevent recurring waiting lists for elective surgery.

And just as the geopolitical environment soured, our defence procurement process failed repeatedly, giving the impression that Admiral Kafka was firmly in command.

To make things worse, the Coalition had countless policies, but no overriding policy, in each of those areas. What, for example, was the Coalition’s long-run vision for the structure of our health system? No one knew for sure, any more than anyone knew how it thought our education system should evolve in the years ahead.

It is true that the growing fragmentation of politics, and the short-term orientation it promotes, hindered addressing those questions, as did Labor’s incessant scaremongering. But it is every bit as true that the Coalition lacked the internal cohesion and political courage needed to properly define its vision, preferring the safety of ambiguity to the dangers of an unambiguous stake in the ground.

Whether those weaknesses are the Coalition’s alone remains to be seen. Labor is certainly more adept at spinning grand narratives; but as was apparent in the Rudd-Gillard-Rudd years, the yawning gap between those narratives and reality makes them useless at guiding harsh choices.

The risk is that just as the wings have been bred off certain chickens to produce more white meat, so we may have bred a political class (and public service) that is congenitally incapable of the serious thought governing requires – and a political system that punishes those who try.

Chalmers opens and closes his essay by citing Heraclitus’s dictum that one never steps into the same river twice. Perhaps: but one can step many times into the same bathwater, and it gets filthier each time. Unless Chalmers rinses off the woolly rhetoric, and shows a capacity for credible and dispassionate analysis, including of Labor’s own errors, yesterday’s muck will also be tomorrow’s.

Infused with the rage of an old testament prophet, the essay Kevin Rudd published in The Monthly 14 years ago promised to expel the money lenders from the temple and purge markets of greed. Wayne Swan’s essay, which appeared three years later, was even more incandescent, vowing to strangle the last mining magnate with the guts of the last merchant banker.