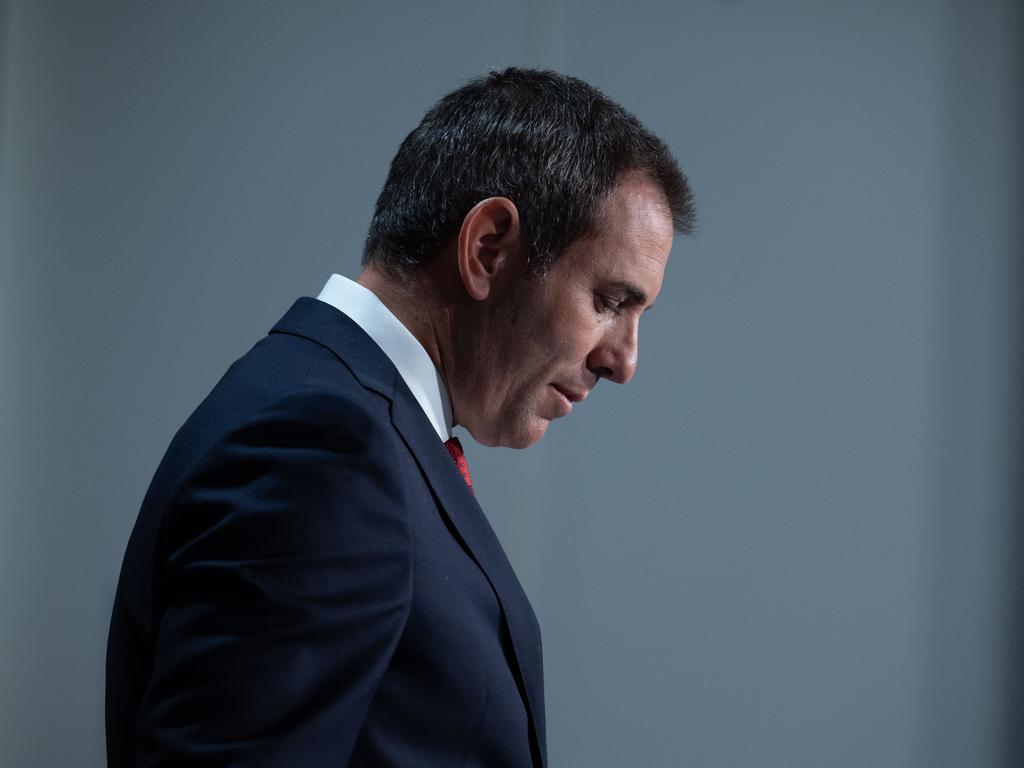

So when Jim Chalmers talks about “reinventing capitalism”, to base markets on “values”, he’s talking about the Labor Party’s values, not yours.

Hence there’ll be even more government interference, dressed up as greater fairness, on your freedom to buy, sell, own and invest. This latest missive, from a Treasurer who hasn’t even had 12 months behind his fiscal desk, reveals a government already looking far more radical than the “safe change” platform it was elected on.

Chalmers’s essay in The Monthly is terrible economics but a very good guide to the real nature of the Albanese government that not only wants to change the way we’re governed but to make government bigger and more domineering than ever, despite the absence of any demonstrable mandate.

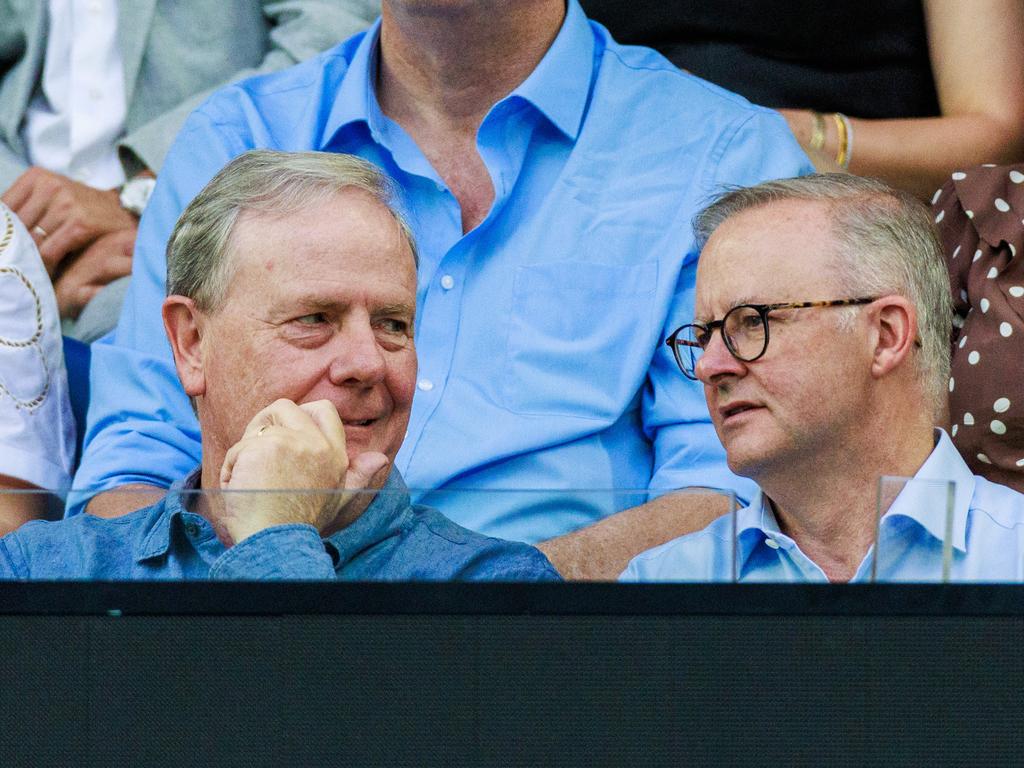

Before May’s election, Anthony Albanese was at pains to reassure us he’d cut electricity bills, raise real wages, and do more on climate, but only in ways that created jobs and boosted the economy. There’d be no deals with the Greens, and his role model would be Bob Hawke, the last Labor prime minister who actually delivered a budget surplus.

Exploiting Scott Morrison’s unpopularity, Albanese skilfully created the impression all he really intended to change was the identity of the prime minister. But that’s not how it’s turning out.

Pre-election, then-shadow treasurer Chalmers denied multi-employer agreements were “part of our policy” to lull business groups into a false sense of security. Post-election, the law was changed to permit industry-wide bargaining and industry-wide strikes after dragooning business into a “jobs summit” that was a pre-planned stitch-up with the unions; Hawke-Kelty in style but nothing like it in substance.

And there was more. The government pre-empted legislation to abolish the building industry watchdog by first stripping its funding. It then announced emissions-intensive industries would have to buy carbon credits at up to $75 a tonne to keep operating. Most recently, to limit the power price rises driven by attempts to prematurely retire fossil fuels, the government took the unprecedented step of imposing price controls on gas and thermal coal.

Now, the Treasurer has tried to lend a spurious intellectual rationale to this abandonment of economic responsibility via supposedly reinventing capitalism to deal with what he calls the “poly-crisis” of war, pandemic, climate change and inflation. Markets are not perfect but they’re the most efficient way to allocate scarce resources. And what Chalmers finds mysterious and attributes to the failings of markets is much more often the failure of governments: such as today’s inflation due to governments’ unfunded spending to deal with the pandemic, and supply chain bottlenecks due to government-ordered pandemic lockdowns.

Labor has form when it comes to masking economic ineptitude under a thin veneer of moralising. In a 2009 Monthly essay, Kevin Rudd claimed the global financial crisis proved the failings of capitalism. Like Chalmers, he wanted markets with a higher purpose; only in practice, his legacy was massively overpriced school halls, a multibillion-dollar failed pink batts scheme, and billions more spent on hospitals and schools without any commensurate improvement in outcomes.

In early 2012, Chalmers’s then boss, Wayne Swan, also penned a Monthly essay, but his supposedly superior insights into capitalism didn’t save him from the worst economic prediction of all: namely, his 2012 budget boast about “the four years of surpluses I announce tonight”, of which none ever arrived.

Chalmers asks: “How do we build this more inclusive and resilient economy?” His answer: “By strengthening our institutions and our capacity with a focus on the intersection of prosperity and wellbeing, on evidence, on place and community, collaboration and co-operation. By reimagining and redesigning markets – seeking value and impact, strengthening safeguards and guardrails in areas of unchecked risk. And with co-ordination and co-investment: recognising that government, business, philanthropic and investor interests and objectives are increasingly aligned and intertwined.”

This pretentious blather is worth quoting at some length because it typifies his essay, which is almost entirely devoid of any meaningful, specific content.

He seems to regard the government’s energy policy as a good example of how values-based capitalism might work. And it’s true that as long as there are consumer subsidies and government incentives for renewables, rent-seeking investors will rush to install more wind turbines and solar panels.

Unfortunately, apart from the inflated profits of the businesses restricting supply, the result of too much intermittent and not enough reliable power is much higher prices to consumers and the likely loss of all our heavy industry to jurisdictions that don’t care about how power is generated; just that it’s cheap and 24/7. The problems in our energy markets are much less from any market failure than from successive governments trying to run them to reduce emissions rather than for optimal power generation.

The Treasurer also seems to regard the nation’s compulsory superannuation balances as the perfect place for governments-that-know-best to partner with impact investors to advance a “social purpose economy”. In practice, though, this means the union-dominated super funds not investing our money to maximise returns to us but to meet the political imperatives of government.

What Chalmers fails to appreciate (and his doctorate is in political science, not economics; his thesis was “Brawler Statesman: Paul Keating and prime ministerial leadership in Australia”) is that what he refers to as “capitalism” is just ordinary human freedom in the economic sphere.

No country has taxed and regulated its way to prosperity, although plenty of governments have tried; always to their citizens’ cost. Likewise, while there are some things that only government can do, such as defending the nation and exercising physical force over citizens, there are no goods or services the public sector can provide more efficiently than the private sector, if the private sector is prepared to invest.

Chalmers is going beyond the obvious point that markets can only operate within a framework of law that government sets. His sermonising against the way markets have operated in Australia, including under the Hawke government, can only mean more regulation, higher taxes, sweetheart deals with rent-seeking big business and big unions, and government forcing money to move from more to less efficient parts of the economy.

“Reinvented capitalism” means stopping us from doing what we want, in favour of forcing us to do what government wants. If Chalmers’s essay is the government’s road map, forget the PM’s spin about emulating Bob Hawke. It’s on a Whitlam-esque path to becoming the most left-wing government in our history.

It’s not often I quote Paul Keating but his declaration, “when you change the government you change the country”, encapsulates the left’s mindset for government. To the left, government exists to pursue an aggressive agenda, using the organs of state to remake individuals, institutions, and society. Whereas to the right, government’s purpose is only to do what citizens can’t do for themselves, hence government should normally be smaller, not bigger.