This means we have seen horrible consequences in some countries; millions of deaths, social disruption and health systems overrun. Measures to contain the spread of the disease have also been debilitating; cities locked down, borders closed, and travel suspended.

But the fear it is has instilled in many has triggered some surprising responses that are unwarranted and disproportionate. Take, for instance, the now routine rush for toilet paper every time there is an ominous outbreak – it is borne of a headlong rush towards lockdown, the need to muster essentials for an extended period, and perhaps more importantly, the human need to be doing something rather than passively awaiting our fate.

It is amusing and yet quite disturbing to witness, but it is only the most obvious and comical of our irrational responses. In the past six months, South Australia, Melbourne, Perth (twice) and Brisbane (twice) have locked down over small outbreaks (sometimes just a single infection) and the responses were proven to have been superfluous – the virus had not spread beyond close contacts who had been isolated already.

Politicians are reflecting and reacting to public responses that are panicked, risk averse and emotive. A rational approach would balance costs and benefits, risks and rewards, and accept a certain level of exposure to this disease rather than shutting down, isolating, and either trying to eliminate the disease or sit it out.

One of the reasons this is irrational is that the disease might well be part of our lives for years, if not decades, to come. Hiding likely is not a viable long-term option.

It is also unsustainable because every time we borrow to get through this crisis we condemn those who come after us to pay for our current reaction. We owe it to our children not to burden them with our paranoia. They might have crises of their own to deal with – yet we selfishly decide to draw down on their future taxation in the hope we can sit out this pandemic.

There are no clear-cut answers here, not without knowing the future, but these are the complications, contradictions and compromises we need to deal with. And these are the forces that have played out in a 2021 federal budget that owes much to this tortured contest between emotionalism and rationalism.

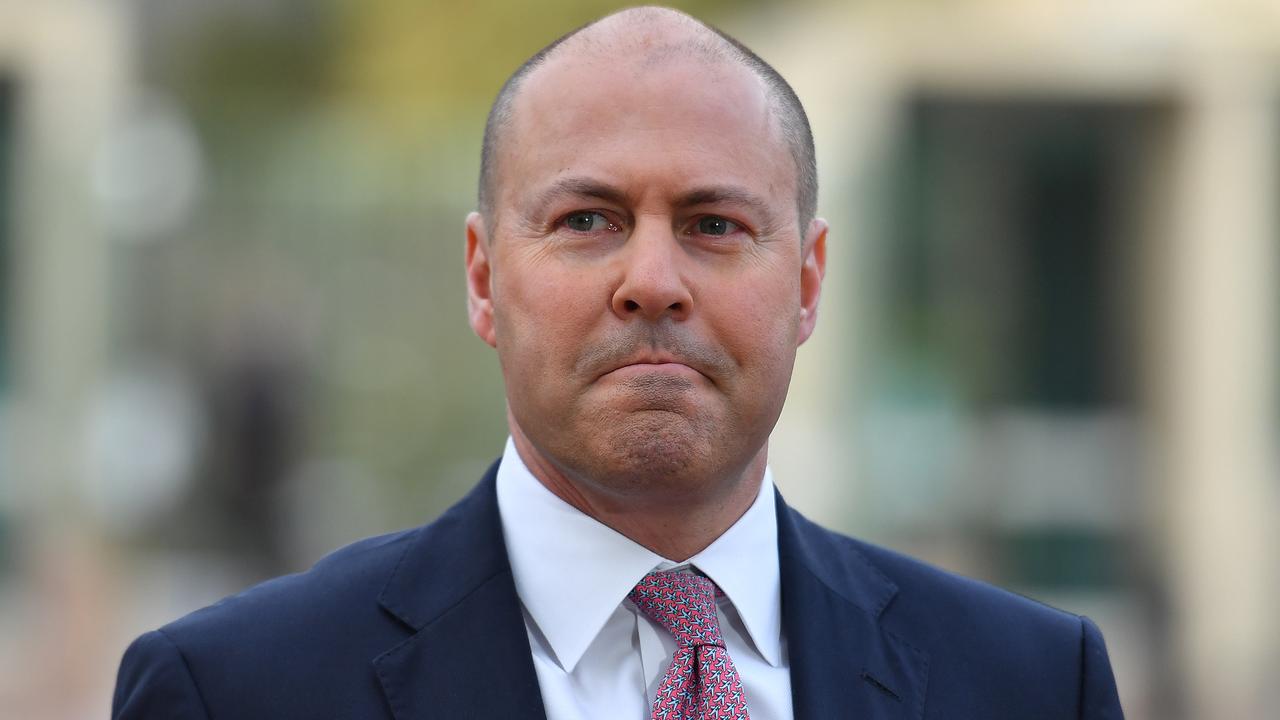

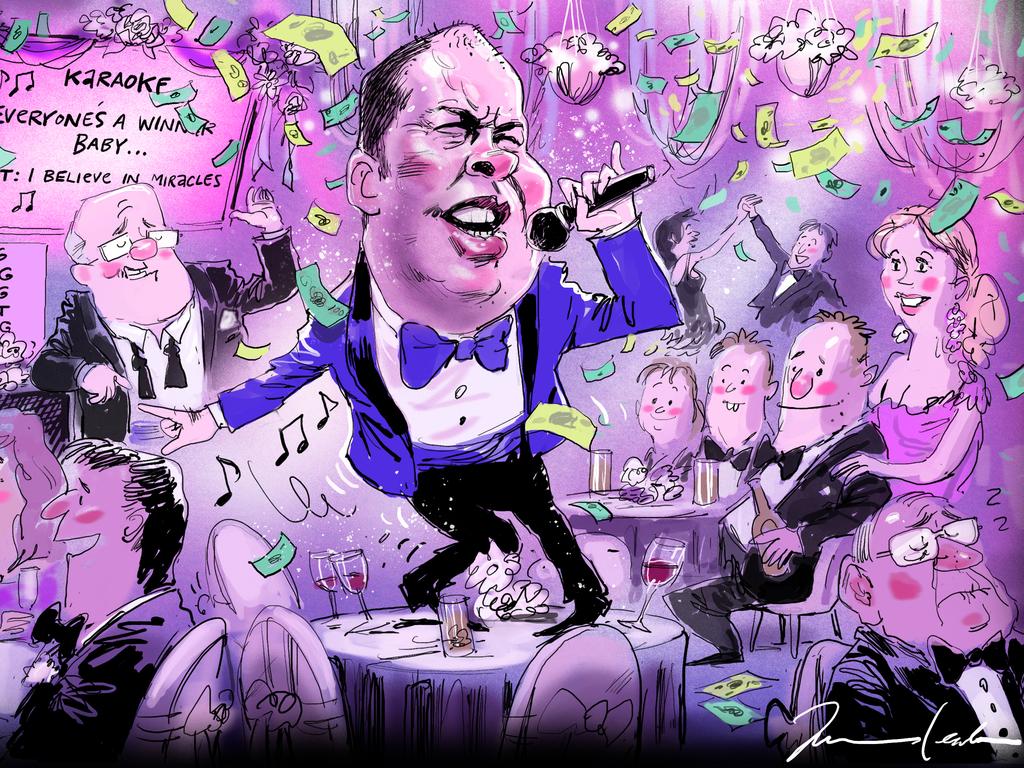

When Josh Frydenberg revealed his massive JobKeeper package I said in these pages that he and Scott Morrison would claim hero status if they could ease us out of the pandemic without spending the lion’s share of it. To their credit, they have done better than they budgeted for, to the tune of more than $50 billion, and our resilient economy is both the proof and the result.

But the real story of this budget is that instead of banking that success, and taking the opportunity to constrain our debt, and keep our fiscal situation closer to balance, they decided to spend the extra money anyway.

Budget 2021: The big picture — what the budget means for you

Instead of spending less and focusing on working to open up the economy and returning us to something approaching a vaccinated normal, Frydenberg and Morrison have decided to embrace an extended sense of crisis, heave money out to a range of worthy and politically-sensitive causes, and deliver an election budget.

In doing so they have demonstrated perhaps one of the most telling side-effects of COVID-19; it has eliminated the economic policy divide between our two major parties. The traditional contrast between the fiscal rectitude and small government leanings of the Coalition and the high spending, interventionist approach of the Labor Party has fallen by the wayside.

The Coalition can no longer mock Labor’s debt and deficit record – now almost a decade in the past – because it has embraced huge licks of debt to fund new and improved services for the aged and people with disabilities, as well as boosts for training, health initiatives and child care. There are no budget losers – except perhaps those not yet in the workforce who will one day have to pay for all this.

When COVID-19 first emerged less than two years ago, the Coalition parties in this nation believed wholeheartedly in balanced budgets, smaller government, constrained debt, and the ensuing lower taxes. Now we have the largest deficit in our history, debt accelerating to an unprecedented level, government spending making up 27 per cent or more of the national economy, the prospect of all this remaining the same for the foreseeable future, and no significant political constituency complaining about it.

That is one powerful virus. And it will take a long while to eliminate.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome 2, or COVID-19, is an extraordinary virus. We know it is highly contagious and can cause fatal complications, mainly in the elderly.