According to the diocesan authorities, belief in the jovial, white-bearded gentleman was a monstrous heresy, and his incineration in front of 250 children highlighted the Church’s determination to protect Christmas’ sanctity.

They were, of course, hardly the first to denounce the conflation of the sacred and the profane in the Christmas celebrations. Already on New Year’s Day, 400AD, Bishop Asterius of Amasea had preached a fiery sermon denouncing the “sordid” gift-giving which “teaches little children to be greedy”.

Endlessly repeated in subsequent centuries, those denunciations proved spectacularly ineffectual. The holiday certainly evolved; but many of its core features remained anchored in its origins, which most historians trace to the ancient Roman festivals leading to the winter solstice, when the hours of daylight start clawing their way back from Europe’s long night.

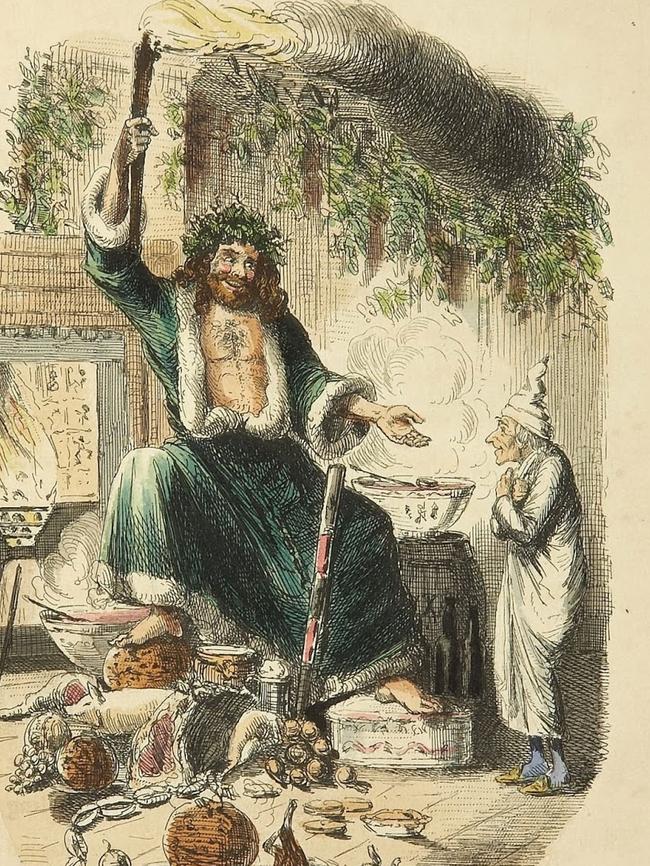

Those festivities’ religious component centred on Saturn, who, until he was chased out of Olympus by his son Jupiter, had presided over a golden age of peace and plenty in which all men were equal.

Recreating that golden age, the December “Saturnalia” suspended the normal rules of Roman life. Trials were paused, as were hostilities; amnesties were declared; and most importantly, slaves were allowed to freely address, dress like and eat with their masters, who were expected to offer them gifts. Suspended too were the rules of civil propriety: as drunken soldiers caroused through the streets, scholars such as Pliny, who valued tranquillity, fled to rural retreats.

The triumph of Christianity completely changed the festivities’ religious focus and extended their scope. Christmas itself became a pivotal point in a series of holy days that began in November’s darkness with the commemoration of the dead and culminated, just after the solstice, with the celebration – in the birth of Christ and the Epiphany – of new light and new life.

But basic elements of the traditional festival – wonder in “a world turned upside down” and exchanges between unequals in the community – persisted, along with the notion of a period free of everyday constraints.

Those elements merged in late Medieval Europe, when meandering, usually drunk, youths and labourers “mummed” their way from house to house, cajoling the rich into “gifts” of food and drink. Christmas therefore served not only to reaffirm spiritual values; it was laden with carnivalesque features that allowed accumulated social tensions to be released, enhancing social stability.

However, as urbanisation created communities of strangers who lacked ongoing personal ties, Christmas “mumming” turned increasingly violent. Reporting on widespread disturbances in 1833, the Daily Chronicle complained that “riot and uproar prevailed, uncontrolled and uninterrupted [while] gangs of boys howled as if possessed by demons”. And according to the London press, Christmas in Australia, where social deference was even weaker, “passed in riot and disorder”.

It was against that threatening backdrop that the great Victorian redefinition of Christmas occurred. Nothing more clearly highlighted the change than the contrast between Charles Dickens’s Pickwick Papers (1837), with its scene of a rural wedding on Christmas Eve – at which no children are present and Christmas itself barely features – and the celebration of family and childhood that, only six years later, is the defining feature of A Christmas Carol (1843).

Propelled by a wave of Protestant evangelism and facilitated by rising affluence, Christmas was transformed into a private, intensely sentimental affair, centred on childhood innocence. In the process, the exchange between social superiors and inferiors that originated in the Saturnalia became an unrequited transfer from adults to children.

Even before then, children had, for sure, figured as carollers and received modest Yuletide gifts. But the gifts, which were conditional on good behaviour, were not an entitlement. And far from being cheery and benevolent, the gift-bearers could be positively frightening, with the Italian Befana using her long needle to stab some children through the heart.

As all that vanished in a steam bath of kind-heartedness, a newly prominent deity – Santa Claus – moved to centre stage. That deity’s distinctive feature was that children believed in it while grown-ups did not, establishing a new rite of passage: the age of innocence ended when the pretence that Santa was the source of gifts lost its sparkle, signalling the child’s encounter with doubt and with the reality principle.

But rather than the focus on childhood innocence abating once that had happened, the warm glow of nostalgia for when the magic still worked infused families’ annual celebrations.

The domestication of Christmas also radically curtailed its traditional function of releasing social tensions, shifting that role to pre-Christmas parties and to raucous cavorting on New Year’s Eve. It was on those adult-centred occasions, whose importance grew as the taming of Christmas proceeded, that participants could “raise hell”.

Now, however, even they are being ever more strictly policed. That is, no doubt, a good thing, eliminating a great deal of boorish stupidity. But one doesn’t need to be a Freudian to fear that aggressive drives resemble a sausage: squeeze them in one place, and they re-emerge, every bit as malignantly, elsewhere. And whatever the new puritanism’s merits, it has its costs.

No one feels those costs more acutely than your correspondent. As the shadows cast by age lengthen, and the blaze of imagination dims to a pale flare, Santa could scarcely restore my long-gone innocence; but is it truly ignoble, one wonders, to wish for the gift of a mildly debauched old age, happy, red-nosed, free of the burdens of respectability and of the stresses of thinking straight? Or has it become so exceedingly difficult in these righteous times to achieve a state of pleasant and continuing dissipation that even Santa must, in that respect, be thwarted?

Perhaps it has – in which case, The Australian permitting, it is more years in the salt mines for Ergas. At least I won’t be alone: our Christmas Price Index, which measures the cost of The Twelve Days of Christmas, reveals that (adjusted for overall inflation) the real income of the Leaping Lords and Dancing Ladies has halved since 2010.

As the aristocrats toil to make up the loss, we will share pickaxes, while glancing enviously at the Maids, Pipers and Drummers who, bolstered by a 20 per cent rise in real income, can bask in princely retirement.

Such is the democratic temper of the age: no point shouting back at its gobbling whirlwind. Fortunately, the joys of the season remain. There really is wonder in childhood innocence, and in its remembrance; the ancient dream of a respite from difficulties and daily dreariness still shines bright; and we can still marvel at discovering unseen bridges that reconnect us to friends long separated by the world’s vicissitudes.

Most of all, however, there is Christmas’ promise of new light and new life, now made especially vivid by the horrors of terrorism and the distant thudding of war.

“The ordinary”, wrote James Joyce, “is the proper domain of the artist; the extraordinary can safely be left to journalists”. Allow me, in that spirit, to thank you once again for your patience and support over the year; and to wish each and every reader a Christmas and New Year blessed with the extraordinary peace all people of goodwill so badly need, and so richly deserve.

At 3.30pm on December 23, 1951, Father Christmas was burned in effigy on the forecourt of the Cathedral of Dijon, the capital city of Burgundy.