Will mounting debts spoil the global sharemarket rally?

Mounting debts are not the issue for global sharemarkets, rather the question is whether the relevant economies have the capacity to finance their obligations.

Amid surging equity markets, it’s reasonable for investors to question the rally’s longevity and speculate about the trigger for its reversal.

This is especially common among those who have elected to sit out the current boom.

The most common concern levelled at equities by those who fear a market correction is that global debt is at record highs.

It’s important to understand those concerns. In a given fiscal year, when a government’s spending exceeds revenue, a budget deficit results. The federal government borrows to pay for the deficit by selling securities such as bonds, bills, notes, and – in the US – Treasury inflation-protected securities (TIPS).

Each nation’s debt is the accumulation of this borrowing and the interest owed to the investors who purchased those securities. As a government experiences recurring deficits, which is not unusual, their national debt grows.

According to the Institute of International Finance, global debt rose by $US2.1 trillion in the first half of 2024, and reached an unprecedented $US312 trillion by the end of June, driven by borrowing in the US and China.

And according to the US Treasury, the national debt of the US reached $US35.46 trillion this year. To put that in context, it was $US395bn in 1924.

But looking at the total debt fails to account for a nation’s ability to repay. In response, what many economists do is compare the debt to a nation’s GDP because it presents the burden of debt relative to the country’s total economic output and its capacity to repay it. In the US the debt to GDP ratio surpassed 100 per cent back in 2013 when both debt and GDP were about $US16.7 trillion.

The International Monetary Fund says the country with the highest debt to GDP is Japan at 261 per cent thanks to its ageing population requiring social support, and shrinking working population, reducing economic output. Greece (177 per cent), Venezuela (158 per cent), Italy (144 per cent) and the US (121 per cent) fill out the top five.

While a high debt/GDP ratio isn’t good, the ratio doesn’t offer any insights into the point at which investors should be concerned.

Perhaps in response, former research director at Salomon Bros, Michael J. Howell developed the concept of “global liquidity”. Howell says the ratio of debt to liquidity is more meaningful. We’ll come back to that in a moment.

Financial crises come in various shades. That fact is best explained through the lens of a history of financial crises in the ground breaking book This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly. Co-authors Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth S. Rogoff present the spectrum of crises – including government defaults, banking panics, and inflationary spikes, examining them across 66 countries and eight centuries.

Their analysis arrives at a simple and powerful conclusion: while times change, crises often exhibit more similarities than differences throughout history.

Howell posits a common trigger for financial crises is debt refinancing complications.

High levels of debt, which exist today, and leverage are acceptable until they can no longer be rolled over or sustained. For continuity and stability, liquidity is required.

The problem is that while debt continues to grow, liquidity tends to behave cyclically.

Meanwhile, governments and central banks are simultaneously distracted trying to achieve durable growth, maintain functioning markets, and stable inflation and be re-elected.

Howell notes that since 2001 world debt has accelerated. That coincided with the entry of China into the World Trade Organisation. As China dumped cheap products on the West, inflation plunged, and central banks, worried by deflation, cut rates to ultra-low levels, stoking a borrowing binge.

One might also add the desire to avoid another Great Depression following the GFC also prompted global central banks to cut rates to zero.

If one assumes an average term for the world’s $US350 trillion of debt of about five years, about $US70 trillion needs to be financed each year, says Howell.

His research says that when the debt/ liquidity ratio is above average the world experiences “refinancing tensions” and crises. When the ratio is below average, abundant liquidity produces asset booms.

So it all comes back to liquidity. In Australia’s case, consumers had plenty of work and therefore had the liquidity to meet the higher repayments as low fixed-rate mortgages rolled on to higher variable rates. That why the “mortgage cliff” never happened.

Similarly, Howell notes there is no need to panic just yet. Acknowledging record levels of debt make Western financial systems vulnerable, he notes the deterioration in debt/liquidity is a process rather than a single event.

Could late 2025 mark the peak of the equity market rally? Given the uneven distribution of information and money, I have previously indicated that 2026 would leave enough time for a bull market that began in 2022 to have transformed into a bubble.

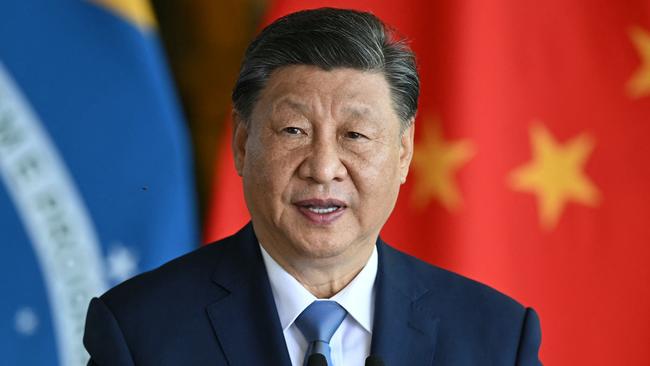

It is also worth noting Chinese President Xi Jinping’s stated objective of being prepared by 2027 for an invasion of Taiwan.

At that point an elevated market with high price-earnings ratios would be vulnerable to any shift in sentiment. Whether that shift is triggered by debt-to-liquidity levels causing a GRC (due to debt refinancing, China’s economy collapsing or accelerating inflation) or to escalating geopolitical tensions, we don’t yet know.

But as Howell concludes, investors may want to start dancing a little closer to the door as 2025 progresses.

Roger Montgomery is founder and CIO at Montgomery Investment Management

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout