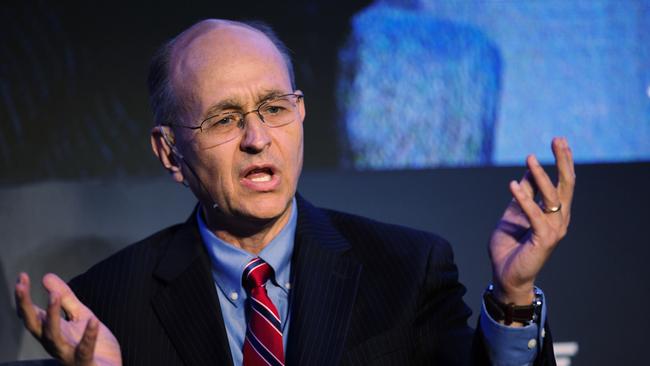

Oil, debt and China are the risks that lie ahead, according to Citi’s Nathan Sheets

For Citi’s New York-based global economist, Nathan Sheets, the difference between a recovery and global recession are finely balanced.

There are three real stresses that threaten to derail the tentative global recovery. And in the long arc of economics they are all interrelated: Oil, China and debt.

The most pressing of these concerns is geopolitics and what that means for oil markets.

According to Citi’s New York-based global chief economist, Nathan Sheets, further escalation of a conflict between Israel and Iran that spills into physical oil supply in the Middle East is where the economic tension is centred.

Given the higher correlation of oil to the global economy, the shock could be bigger than the gas price surge when Russia invaded Ukraine.

There has been some reprieve on this recently because, according to a Washington Post report, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu prefers a counterstrike on an Iranian military facility rather than its oil or nuclear infrastructure. That doesn’t mean the conflict is going away.

For Sheets, a one-time Fed official and former adviser to the US Treasury on international affairs under Barack Obama, that’s how finely balanced the risks are.

“So far there has not been a disruption in physical oil supply, but if something happened to shut in some barrels, you could see oil prices rise,” he says.

“That would be challenging to markets and to the economy. It would create uncertainties, could be inflationary and represent a supply shock that central banks would need to think about how they were going to manage.”

A slowdown in China represents another risk. This one is better known. With or without more stimulus measures, this could be a problem that persists into the medium term.

The challenge for China is consumers are very cautious and concerned. And as they look to the future they see a lot of things to worry them: Debt leverage, property, ageing demographics and high youth unemployment, geopolitical pressures and fragmentation.

Combined, the concerns mean there is likely to be caution across China over the medium term.

This is why authorities are struggling to jump-start the consumer sector, despite a round of measures unveiled last month. There are noises about fiscal policy coming this month.

The US presidential election in November represent volatility over risk. Sheets says the markets are approaching Kamala Harris as the continuity candidate. But with Trump there will be uncertainty as “you’re moving from one approach to another”.

Australians might feel like the country is carrying way too much debt. But among its developed economies it is the poster child of thrift. Its government debt and fiscal deficits are still in the green zone placing it behind Germany.

The US is running a public debt at 122 per cent of GDP (it’s less than 50 per cent here). Others like the UK, France and Italy are above 100 per cent. China is rising through the ranks at 75 per cent. Japan is pushing 250 per cent. In all cases there’s little discussion about bringing debt under control.

Debt “worries me for the US. It worries me for the UK. It worries me for Japan”, Sheets says.

“The risk is that at some point the markets say we don’t want to hold all this debt, and maybe that is a bubble, but we’re pushing the market’s willingness to absorb the issuance.”

Sheets was speaking to The Australian on the sidelines of the Citi Australia Investment Conference in Sydney, where he pointed to encouraging signs the global economy was returning back to its long-run average after first being derailed by the pandemic and then the severe inflation shock that followed.

“We see global trend growth around 3 per cent. Growth this year is maybe coming around 2.5 per cent, but broadly in the neighbourhood of normal,” he said.

Added to the positive momentum is the prospect that US rates are coming down. And fast.

After last month’s 50 basis point cut, taking the US rate to its upper bound of 5 per cent, Sheets tips further cuts in November and December – although the size of the cuts will be data dependent. Then going into next year he expects the US Federal Reserve to cuts rates to around 3 per cent which will be the new neutral.

Over the past decade the US neutral rate (neither expansionary nor contractionary) was considered around 2.5 per cent. The reason behind the need for a higher rate? Technology.

“There’s going to be somewhat more growth impulse in the US economy that existed before the pandemic,” he said.

“I think that we are in the midst of an AI transition that’s likely to drive the economy and create a little bit more momentum around demand, as well as supply in the economy.

“And so that’s going to mean the Fed’s going to have to be a little bit tighter in order to preserve balance, because there’s this new kind of engine that will be in play,” Streets says.

Card fight

Treasurer Jim Chalmers has declared he wants them gone and the Reserve Bank at least wants to bring them down. But in a crackdown on hated debit and credit card fees, the 800-pound gorilla of the payments system is yet to be tackled: Apple.

Banks hope the RBA will soon be given power to bring the likes of Apple and Google and others into the labyrinth of Australia’s payment system and this will pave the way for real reform.

Increasingly, cashless payments are being made through digital wallets operated by Apple or Google and the fees the tech giants charge for this to happen are going offshore and aren’t being used to build out Australia’s payments plumbing.

It comes as the central bank has, as expected, launched the latest of its regular reviews of the payments system. Where buy now, pay later was all the rage in the last review in 2019, this time it’s about who is footing the bill for the technology behind cashless payments. The answer is consumers.

With nearly eight out of 10 payments made by card or cashless in Australia, the Reserve Bank’s review will tackle why average fees for card payments haven’t fallen with more technology and payment options for consumers. This has put much-hated surcharging in its sights. Other payment mechanisms such as mobile wallets will be looked at a later date when the RBA finally gets the powers to deal with tech majors.

However Chalmers’ dramatic intervention on the eve of the RBA review is unhelpful given it’s an extremely shallow way of looking at how the complexity of the payment system works.

It is like declaring all road tolls should be abolished: A great idea in principle, but in practice would have a number of unintended consequences, including who wears the cost of infrastructure.

Aussies paid almost $2bn in credit card and surcharge fees last year and the RBA rightly argues this is too high. There has to be some sort of benefit from economies of scale. At the same time there is little transparency with consumers not really having any visibility about the fees being charged.

Indeed this lack of visibility is helping to keep costs high with most contactless transactions being routed through higher cost Visa and MasterCard schemes rather than the lower cost Australian platform Eftpos.

Australian surcharging levels are some of the highest in the world and sit behind the US where fees have been set for more than a decade. At the same time smaller merchants (retailers and businesses) are likely to face higher fees for using payments infrastructure where big merchants with high payments volumes can negotiate favourable rates. The fees for small merchants vary widely and this lack of pricing power is ultimately passed on to the consumer as a direct charge.

The RBA has laid out three positions in its reform plans. Eliminating debit card surcharging, banning all card surcharging, or capping interchange and scheme fees, which is likely the preferred path.

A ban is the nuclear option as this pushes fees back on merchants, which in turn would seek to recoup payments costs by raising prices or limiting payment options. The hit will be felt most by small to mid-sized businesses which will no doubt campaign hard going into an election.

The very idea of a ban slammed the shares of payments challengers Tyro and New Zealand’s Smartpay which were down 11 per cent and 17 per cent respectively. A ban would be bad news for Australia’s payments platform Eftpos. Meanwhile, Jack Dorsey’s Block which owns Afterpay and remains untouched under the RBA review jumped 3.1 per cent.

A cap on the fee is the likely middle ground. This will see the banks argue for a situation such as in water or energy infrastructure where there’s a standing or access fee and a user charge on top that. That will simplify payments costs on merchants and consumers.

The Treasurer’s wish about the fees disappearing still mean the cost needs to come from somewhere. The argument has been the fee revenue pays for the cost of running the network and encourages innovation as well as safety and reliability in the sector.

These are the issues the RBA is going to have to grapple with.

eric.johnston@news.com.au

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout