Wall Street pauses trading as stocks plunge more than 7pc

US joins an oil-fuelled global market rout with a 7.8 per cent dive after plunge triggers first trading time-out since 1997.

US stocks careened on Monday, pushing major indexes closer to bear-market territory as a price war for oil and the fallout from the coronavirus frightened investors, who sought shelter in government bonds and propelled yields to unprecedented lows.

The selling was heavy across markets and geographies, with investors seeking shelter in government bonds and sending Treasury yields to new lows. US stocks fell hard enough after the open to trigger a 15-minute trading halt.

LIVE | TradingDay blog — ASX set to be smashed

The Dow sank 2,014 points, or 7.8 per cent, to 23851, its sharpest daily decline since 2008. The S&P 500 fell 7.6 per cent to 2746. And the Nasdaq Composite slid 7.3 per cent to 7950.

All 11 sectors in the S&P 500 were down, led by energy, which slid 17 per cent. Financials were down 11 per cent, and industrials were down 8.9 per cent.

When the circuit breaker hit, the Dow and Nasdaq were down 19 per cent from record highs set earlier this year and the S&P had fallen 18 per cent from its peak, leaving them on the brink of bear-market territory. A drop of 20 per cent from the highs would halt a bull-market run that began after the financial crisis — stocks bottomed out 11 years ago to the day, on March 9, 2009.

“The 11-year bull market is over,” said Peter Cecchini, the chief market strategist at Cantor Fitzgerald, noting that it isn’t just about an official 20 per cent drop.

Mr. Cecchini said central banks suppressed interest rates over the years, and that became a big narrative investors used to justify buying stocks. Meanwhile, signs have emerged that global growth was slowing, like the inverted yield curve late year, but were ignored, he said.

“That underlying backdrop of fragility is one of the reasons why this has unwound so quickly,” he said. “When a bubble extends this far, it doesn’t take much to prick it.” Saudi Arabia’s decision over the weekend to instigate a price war as it escalates a clash with Russia sent oil prices down by the most since the Gulf War in January 1991. Crude prices, along with US government bond yields, are typically viewed as key barometers of economic health and confidence, said Gregory Perdon, co-chief investment officer at private bankers Arbuthnot Latham.

“There has always been an assumption that when the oil price collapses the world is going to become a darker place, whether that is driven by the demand side or supply side,” Mr. Perdon said. The latest tensions put the oil market in somewhat uncharted territory with pressure in terms of both supply and demand as the coronavirus epidemic threatens to sap businesses’ appetite for energy.

The plunge in crude added to two weeks of turmoil in equity and credit markets as investors have grown increasingly concerned about economic growth stalling. It also raised fresh concerns about the risks tied to heavily indebted energy companies in the high-yield market, and the fallout for other companies if broader credit markets tighten.

US government bonds, which have already rallied to unprecedented highs, extended gains. The yield on the 10-year Treasury, which moves inversely to bond prices, dropped to 0.526 per cent. The 30-year yield fell below 1 per cent, recently at 0.959 per cent.

“The fear today is about a global recession,” said Thomas Hayes, chairman of Great Hill Capital, a hedge fund-management firm based in New York. “If Russia does not come back to the table soon, investors worry the default risk and credit spreads widening will lead to tighter credit and even a recession.”

Public-health authorities are escalating efforts to contain the coronavirus outbreak, leading to a drop in business activity and curtailing global trade. The number of confirmed coronavirus cases has exceeded 110,000, with over 3,800 fatalities globally. At least eight American states including New York have declared states of emergency as infections spread to new parts of the US, and Italy quarantined some 17 million people.

Brent crude, the global gauge of oil prices, shed 19 per cent to $36.75 a barrel, while US crude futures recently dropped 17 per cent to $US34.09 a barrel.

US energy producers were among the hardest hit. Chevron dropped 13 per cent and Exxon Mobil fell 9.5 per cent. Occidental Petroleum slid 35 per cent.

Rising defaults among US energy producers may make it harder for companies in other sectors to access credit markets, analysts said. “That ultimately is the negative aspect to lower oil,” said Viktor Hjort, head of credit strategy at BNP Paribas. “There is a real risk, and that is tighter credit conditions.” The price war between major oil producers is “throwing petrol on the fire” while investors are struggling to understand how deeply the outbreak will impact global supply chains and consumer spending, according to Lyn Graham-Taylor, a rates strategist at Rabobank.

“We have got a massive demand decline brought about by the virus and now you’ve got headline inflation going through the floor: all combinations that say we need to do more easing,” Mr. Graham-Taylor said.

Stocks in the European energy sector led markets lower in the region, with BP plummeting 20 per cent in London. Anglo-Dutch firm Royal Dutch Shell, Norway’s Equinor, Italy’s Eni, the U.K.’s BHP Group and France’s Total were also among the big decliners.

That led the pan-continental Stoxx Europe 600 index down 7 per cent with key equity benchmarks in the U.K. and France entering bear-market territory.

Foreign-exchange markets also faced renewed volatility on Monday, as steep drops in oil sparked a flight from commodity-linked currencies. The Russian ruble lost 8.3 per cent, while the Norwegian Krone dropped 2.8 per cent.

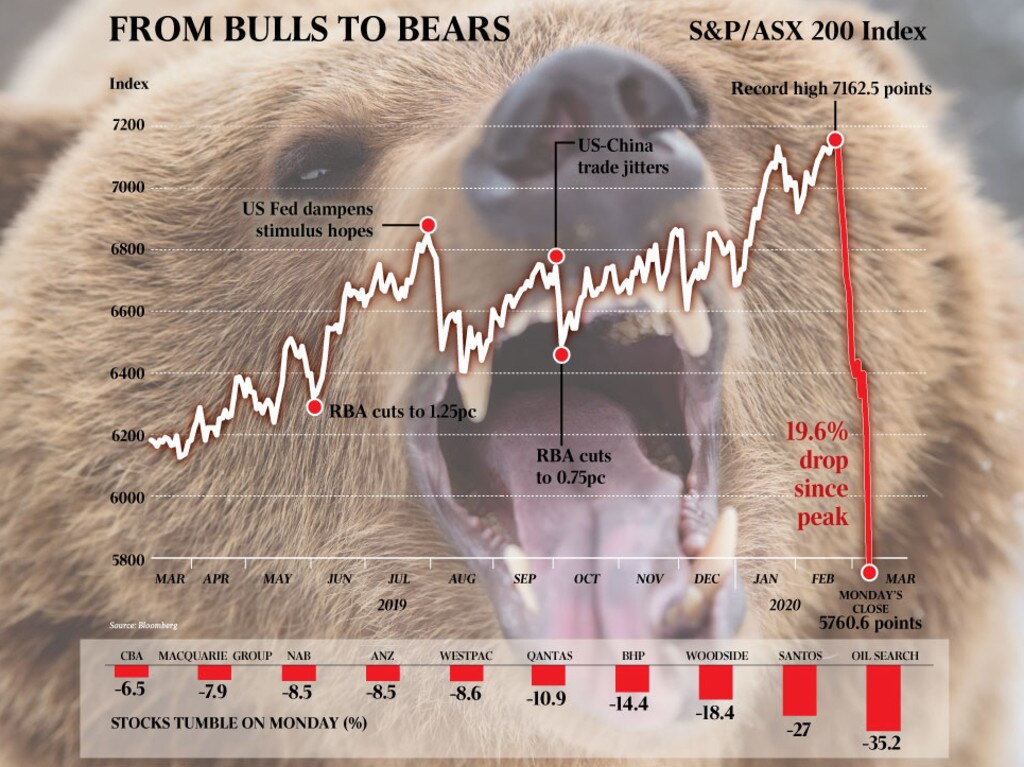

In the Asia-Pacific region, the S&P/ASX 200 index in Australia dropped 7.3 per cent, suffering its worst day since October 2008. Japan’s Nikkei 225 index closed down 5.1 per cent, its biggest daily drop since 2016.

The Japanese yen, which often rallies in times of market stress, surged 2.9 per cent to trade below 103 to the dollar, at its strongest levels since 2016. Gold, which is also normally considered a haven asset during times of turmoil, edged up less than 0.1 per cent.

“We are in uncharted territory now,” according to Hubert de Barochez, markets economist at Capital Economics. “Up until last week, what we were seeing was bond yields lower, stocks hurt and riskier currencies getting hit, but the idea was that if good news were to come all these moves would revert.” Xie Yu and Akane Otani contributed to this article.

With Avantika Chilkoti, David Winning

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout