‘Kamala’s Way’ review: Getting to know the next in line

In truth, scrutiny of a kind more exacting than normal has already fallen upon Kamala Harris: the Vice-President was the running mate of a man who has just become the oldest president in US history. So it isn’t necessarily ill-mannered to ask what sort of successor Harris would make were her genial but time-worn boss fail to finish his first term.

It is safe to say, after reading Kamala’s Way, that Americans who range right from the political centre will be mighty relieved if Biden were to enjoy the best of health for the next four years. As Dan Morain makes plain in this detailed and dutiful biography, Harris is notably less moderate (or, if you prefer, more progressive) than Biden, so, naturally, a source of strength to voters on the left.

Mr Morain, a veteran newspaperman, covered California’s politics for nearly three decades at the Los Angeles Times and then, for several years, at the Sacramento Bee. Kamala’s Way is a story told in a steadfast (sometimes plodding) chronological sequence. It starts at the time Harris’s Indian mother and Jamaican father met in Berkeley, California, in 1962 and runs through to October 2020, when the book ends, poised a hair’s breadth away from an election that would make Ms Harris the first woman/African-American/South Asian vice-president of the US.

Mr Morain reveals that neither Ms Harris nor her family would grant interviews or “provide help in the reporting” of his book, since he wrote it in the middle of the election campaign. But a number of sources with “firsthand knowledge” did speak to him. And he has mined material from Ms Harris’s own autobiography, “The Truths We Hold,” which was published in January 2019 to coincide with the launch of her bid for the Democratic presidential nomination.

The most arresting parts of Mr Morain’s book are those that reveal how far to the left Ms Harris moved in the course of her campaign in 2016 for the US Senate seat vacated by Barbara Boxer — who had held it, limpet-like, for 24 years. Ms Harris’s victory speech — delivered in Los Angeles to campaign staffers deflated by Donald Trump’s defeat of Hillary Clinton — promised a fight against Big Oil and on behalf of student-debt erasure and Black Lives Matter; she also called for bringing undocumented immigrants (in her words) “out from under the shadows.” Once in Washington, she consolidated her position as a leading “Trump resistor” by her warlike interrogations at committee hearings. As Mr Morain puts it: “Old-time Washington hands, especially old men,” had some difficulty with Ms Harris’s “audacity and her tenacity.”

As those last two abstract nouns suggest, Mr Morain is a writer deferential to Ms Harris. Word choices are telling. Jeff Sessions, President Trump’s attorney general until November 2018, is described as offering a “stammered” reply to Ms Harris in the course of Senate Intelligence Committee hearings. Elsewhere, Brett Kavanaugh is “cornered” by a question directed at him by Ms Harris.

The obverse of such a strategy is the taking of a position when political advantage, and not principle, beckons. Mr Morain writes that in a field of Democratic presidential contenders “that included strong women” — such as Elizabeth Warren and Amy Klobuchar — “Harris was not standing out.” She needed to find a way to spice up her campaign. In the first Democratic presidential debate in June 2019, she played what might be called the race card against Mr Biden, berating him for working out compromises with segregationists at an earlier stage in his political career. She added theatrical fuel by saying that there had been “a little girl in California who was part of the second class” to integrate Oakland’s public schools. “And that little girl was me.”

This attack, says Mr Morain, “surprised Biden and seemed to hurt him on a personal level.” Mr Biden told a morning news show that he “thought we were friends, and I hope we still will be.” After all, Mr Biden had, in 2016, stepped in to help Ms Harris stave off a challenge from US Rep Loretta Sanchez, a feisty Democrat who was fighting Ms Harris for the Boxer Senate seat. And he’d done it, in large part, because Ms Harris had worked closely with his late son Beau, a fellow attorney general from Delaware.

The virtue of Mr Morain’s book lies not in elegance, to which it makes no claim, nor in its revelations. (Ms Harris has led a life that is as impressively documented as it is impressive.) It lies, instead, in a prosaic but sturdy completeness of story. Ms Harris — as is her prerogative — omitted much detail from her own autobiography. Mr Morain has filled in many of those blanks, one of which is her relationship in the early 1990s with Willie Brown, a former speaker of the California Assembly and, later, mayor of San Francisco, with whom Ms Harris was romantically involved.

Mr Brown gave Ms Harris two (cushy) early jobs on California state boards, which were controversial not because she was unfit for them but because he had been her paramour. Her latest job is in a different league (to put it gently) from those early sinecures. And there can be few in America—outside a partisan hard core—who would say that she has not earned it.

Tunku Varadarajan is a fellow at New York University Law School’s Classical Liberal Institute.

THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

-

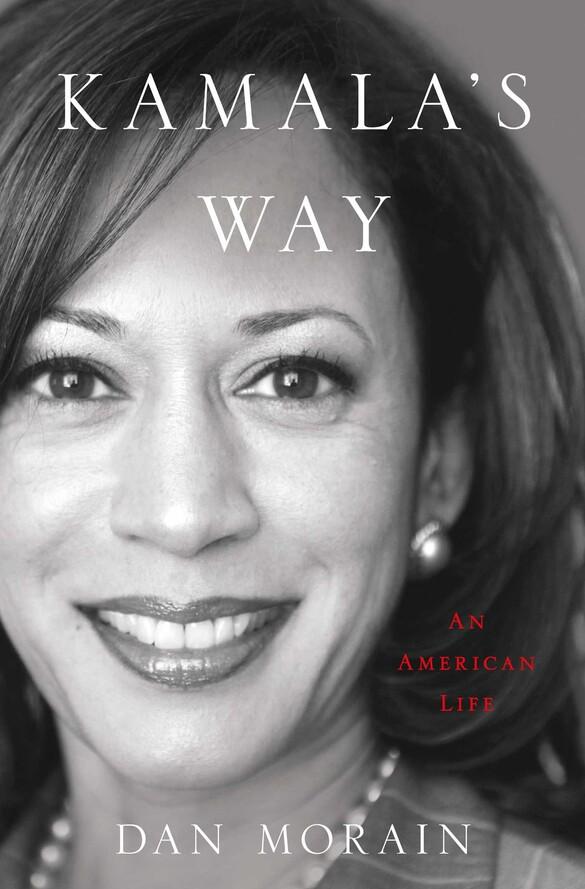

Kamala’s Way: An American Life

By Dan Morain

Simon & Schuster, 272pp, $45 (HB), $32.99 (PB), $14.99 (ebook)

One consequence of the events of January 6 — in which Mike Pence could be said to have protected the US constitution from his own president — should be that American voters come to pay as fierce attention to the mettle of their prospective vice-presidents as they do presidential candidates.