Kamala Harris should embrace her complex heritage

The VP candidate’s grandfather may not have been a freedom fighter but that doesn’t dilute her activist background.

“My grandfather was one of the original independence fighters in India,” Kamala Harris, the Democratic candidate for US vice-president, has said. “I come from a family of freedom fighters.”

The California-born daughter of an Indian mother and a Jamaican father, Harris is rightly proud of her bi-racial heritage: half South Asian, half Caribbean, wholly American.

In her 2019 memoir, The Truths We Hold she described how her maternal grandfather, PV Gopalan, had been part of the Indian independence movement. She may hold that as a truth but the reality, as so often with British imperial history, is rather more complicated.

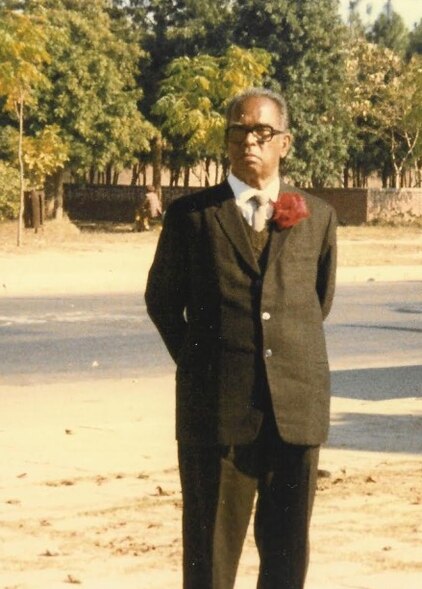

Gopalan was a high-ranking civil servant, a Brahmin bureaucrat from Tamil Nadu who happily worked in the British Imperial Secretariat Service for 15 years without a word of public protest before moving on to serve in the Indian government after independence in 1947. There is no proof that he was active in the independence movement, a political radical, or anti-British.

Harris’s Indian uncle has said that his father was secretly engaged in “bureaucratic manoeuvres” (whatever that means) against the British but no evidence has been produced to back up this claim and other family members in India have candidly admitted that there is “no record of him having been anything other than a diligent civil servant”.

It is entirely likely that Gopalan, like most Indians, welcomed independence from Britain; that doesn’t quite make him a freedom fighter.

In playing up her supposed anti-imperial antecedents, Harris is following Democratic tradition: in his memoir, Dreams from My Father, Barack Obama claimed that his grandfather had been arrested and tortured in Kenya during the Mau Mau uprising against British rule. Those claims are disputed, and may be closer to family legend than fact.

Kamala Harris’s mixed ancestry offers a unique insight into British imperial history at its best and at its worst, a complex story of contrasts, of democracy and slavery, education and exploitation, opportunity and oppression. Both the merits and the crimes of British colonialism run through her family’s past.

The Afro-Caribbean side of her family tree is as knotty and intriguing as the Indian one. Her father, Donald J Harris, was born in Saint Ann’s Bay, Jamaica, in 1938.

He went on to study at London University and Berkeley, California, where he met, and later married, Shyamala Gopalan. A distinguished economist, now professor emeritus at Stanford University, Donald Harris has written about his Jamaican upbringing and the “strong sense of identity which that grassroots Jamaican philosophy fed in me.”

Donald Harris’s grandfather was a pimento farmer. In an article written in 2018, Harris also claimed to be descended, though his paternal grandmother, from Hamilton Brown, an Irish-born sugar planter and slave owner.

Brown arrived in the British colony at the start of the 19th century: he vehemently opposed the abolition of slavery, accused the abolitionist William Wilberforce of “hypocrisy”, eventually amassed some 1120 slaves, and was awarded more than £24,000 (the equivalent of £2.31m ($4.2m) today) under the Slave Compensation Act of 1837.

Some white plantation owners in the Caribbean raped or had illicit sex with female slaves, as they did in the American South, resulting in mixed-race children, but the birth records for these are frequently scanty or nonexistent.

Kamala Harris’s precise genealogical relationship to Brown, if there is one, may never be established, but it seems quite possible that her ancestry reflects some of the horror and trauma of Jamaica’s brutal slaving past.

Cut back to the Indian side of her story and we find a different face of empire. The British Raj was certainly racist and exploitative, but it also installed a functioning bureaucracy, an efficient government, democratic values and an excellent educational system, of which PV Gopalan was a beneficiary.

He was a passionate believer in education, allowing his daughter to go to Berkeley after graduating from Delhi University in 1958, and paying for her tuition and living costs at a time when very few unmarried Indian women travelled abroad. After obtaining her PhD, Shyamala Gopalan became a cancer researcher and a civil rights activist.

Kamala Harris has described the profound influence her Indian grandfather had on her as a child, and how they would walk for hours on the beach discussing politics, democracy and government corruption. “My grandfather was really one of my favourite people in the world,” she once said.

It is politically easier to portray PV Gopalan as a covert anti-British fighter for independence rather than a product of the educated, liberal-minded Indian elite. But the very qualities she says she imbibed from him – broad-mindedness, civic duty, self-improvement, educational ambition – may have come from a man who profited from some of the better aspects of British rule in India.

No one should be a prisoner of their ancestry. Harris’s parents met while campaigning for civil rights in Berkeley: that political activism is her most important heritage.

All families have their myths and stories, and Harris can be forgiven for believing her own. “Grandpa was a freedom fighter” makes a better headline than “Grandfather was a dutiful bureaucrat who flourished under the British Empire”.

History is thorny and nuanced, and British imperial history particularly so. Harnessing the past to serve the political present is a dangerous game, for history is seldom as straightforward as politicians would like.

Kamala Harris, the first black woman US vice-presidential candidate, has a rich double inheritance from two very different parts of the British Empire: rather than simplify or shy away from it, she should embrace that legacy in all its fascinating, contradictory complexity.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout