Legally (very smart)

There are more women than men studying law every year, but the road to the top of the profession is far from straight.

Australia’s first female law graduate, Ada Evans, was told she did not have “the physique to study law” when she applied. Her enrolment was only successful because the dean of Sydney Law School was overseas at the time.

Her journey to the Bar was even more fraught, involving an arduous two-decade campaign. And by 1921, when the Bar finally allowed women in, Evans’ circumstances had changed and she would never practise.

Gender has historically had a tricky relationship with law. Today, female law graduates and solicitors outnumber their male counterparts, but the balance is different at the highest levels of the profession: 42 per cent of judges at the commonwealth level are women; at the Bar, women make up between 20 to 30 per cent nationally of barristers; and at law firms, the percentage of partners is well below parity at about 30 per cent.

So what is it like being a senior woman in law?

The Executive

When Brisbane-based lawyer Jacqui Eager’s five-year-old daughter discovered a friend’s father was a lawyer, she was incredulous. “Wow Mummy, can dads be lawyers too?” she exclaimed.

The irony was not lost on Eager. When she was starting out at McInnes Wilson, there were few women in leadership positions.

Eager worked hard in those early years but says she was also lucky that one of the male partners took her under his wing: she was a partner by her late twenties.

Life and work became more challenging when she had children. The 7.30am non-negotiable start was near impossible with the daycare drop-off, and when she asked to work a day a week from home it was declined.

The Deal: The women's pages

Here’s how to win as a woman

There is plenty of advice offered to women about how to succeed at work, but most of it is wrong.

A user’s guide to being a woman

Jobs, children, politics, lipstick. Women have a lot on their plate at a time when there has rarely been more opportunity or challenge.

The women leading the COVID-19 fight

It took a deadly virus and a devastating pandemic to see the brilliant minds and sheer competence of the women on the virus frontline.

Legally (very) smart: the women who rule the law

There are more women than men studying law every year, but the road to the top of the profession is far from straight.

Wish list for women

It’s been a challenging year for everyone in the workforce but have women been affected more than men? And what does next year hold?

Speak up! It’s time for women to fight their corner

The conversations women have about their careers will often determine their futures. Finding your voice is the first step.

How women investors are gaining power

It’s time were taken seriously as a huge potential pool of clients for financial advisers.

Daddy, where do brains come from?

We need to keep challenging the stereotypes that women are always co-operative and empathetic

Social media, success and sexism

Hundreds of Year 11 girls linked in for The Deal’s special panel discussion with women leaders.

Susan Lloyd-Hurwitz: why there’s no playbook for the pandemic

Australian museum chief executive Kim McKay sat down with Susan Lloyd-Hurwitz, CEO of Mirvac.

MECCA’s Jo Horgan on the gender gap and dark side of the web

Shelley Reys, KPMG partner and chief executive of Arilla Consulting, interviewed Jo Horgan, entrepreneur and founder of cosmetics empire MECCA Brands.

Why women can’t do it alone

We need family-friendly policies but organisations serious about tackling the gender gap need to get men on board.

Science numbers: Covid impacts women researchers

Building the careers of women in our nation’s laboratories is even more crucial in the pandemic.

Eager is now an executive general manager at Slater and Gordon, in charge of a number of legal areas including abuse law. She sees it as akin to a vocation: “Taxing but rewarding work.”

The 38-year-old says the culture of law firms is changing, particularly as more women take on leadership roles.

The Solicitor

“Do you hate women and love money?” That gem turned up in Rebekah Giles’ email a few weeks ago – and that’s just the PG stuff.

As a defamation lawyer representing high-profile clients in sensitive cases – Christine Holgate, Brittany Higgins and Sarah Hanson-Young among them – 44-year-old Giles had built a largely positive profile of her own in recent years. But when she accepted the Christian Porter brief – in the politician’s action against the ABC – it all changed and Giles found herself exposed to a new level of vitriol.

“There was a disturbing element to that case,” she says. “It is a fairly recent phenomenon of people conflating lawyers with their clients – and it should be resisted. It is deeply anti-intellectual and it is troubling.”

Giles believes part of it was a reaction to her gender. “As a successful female, you have to deal with things that would never happen to a man,” she says. “You are sexualised and your sexuality is used as a weapon against you. And it happens in the law all the time. Strong female lawyers are seen as aggressive or nasty. My physical appearance is often linked to descriptions of me professionally.”

How does she respond? “It’s white noise,” says Giles. “The best response is to build a successful practice by consistently achieving great results.”

Giles backstory goes some way to explaining her steely resolve. She grew up in Castle Hill, in Sydney’s bible belt after being adopted as a baby by a very loving Christian couple who fostered hundreds of children over the years. Her biological mother was a teenager when she became pregnant to a Malaysian man she had met during school holidays while visiting her parents who were living and working in Kuala Lumpur. Giles father would die a couple of months after her birth on the 1977 hijacked Malaysian Airlines flight when all aboard perished.

Giles says that as a child she often felt she was from a “cabbage patch”. She looked different with her Malaysian heritage and she felt different. The drive, fearlessness and competitive streak were there from an early age. But if Giles’ life changed, it was during the 2004 tsunami in Thailand in which she was critically injured. She was in her 20s and was so badly disfigured that she would need more than 100 surgeries and will require still more.

She says she was in a dark place: “I was in this broken body and I wanted to scream.”

Eventually back at work at MinterEllison she began to recover Later she would move to litigation firm Kennedys and become a partner before striking it alone with Company (Giles), adroitly capitalising on a largely untapped market for reputation damage.

She advises young lawyers to “be humble” and to make it clear they have a lot to learn. The days of the megalomaniac lawyer are over, she says. When she was young she took every case that came across her desk: “If someone offered me a coffee I would take it, if someone offered me an opportunity I would take it.”

Giles says law is full of smart, hardworking people, many of them experts in their field. But what sets the winners apart is their emotional intelligence.

“Being a lawyer is about giving advice, but for the most part it is about relationships,” she says.

The Judge

When Penelope Kari was accepted into Adelaide Law School, her Greek grandparents were beside themselves with delight. Since then she has had a meteoric rise up the legal ladder. From solicitor, to barrister, to judge at the Federal Circuit Court of Australia by the age of 42. Justice Kari says it wasn’t planned. “I just focused on doing my job and doing it as well as I could and turned off the white noise,” she says.

Both sets of her grandparents arrived in Australia in the 1950s with their children separately, fleeing the devastation of the Greek Civil War. They had no English, no formal education and arrived with little more than the “clothes on their back”. Later, Justice Kari’s parents – who met and married in Australia – worked multiple jobs to send her to a private school. The young girl was keenly aware of her family’s investment of hope and hard work in her education and career.

What has her family made of her latest appointment this year to division one of the Federal Circuit and Family Court?

“Well, they are pretty proud,” says Justice Kari. “It’s not what has driven me but it has coloured my narrative.”

The 45-year-old notes the gender imbalance among judges but argues the bench’s profile should not necessarily be viewed solely through the prism of gender. “I’m not a believer in the boys’ club holding women back,” she says. “It has not been my experience. Not all men are bad, and I think that narrative needs to be told.”

Justice Kari points out that it was men who mentored and championed her as a solicitor and at the Bar and suggests that women, particularly those working in cut-throat industries, can often have complex relationships with each other.

She describes the law as “gruelling” and says doing it well involves long hours that are often mutually exclusive to being a parent.

“It does women no favours to perpetuate the myth that the juggle between the two is an easy one,” says Justice Kari, who has two school-age children. She says she and her husband are a “genuinely committed team”, but while she has extensive family support there are compromises that have to be made.

“I grew up being told you can do anything you set your mind to,” she says. “And that is true – but women have a different mentality and expectation on themselves, and that includes invariably being the nurturing parent and being the wife who makes the meals and all the bits and pieces. If you want to do it all really well, something has to give.”

She recalls coming home from long hours to a husband asking: “Are you here, or are you still at work?” She acknowledges there are changes that would make law more family-friendly: solicitors not sending briefs late in the evening to barristers; judges not sitting before 9.30am so parents can get their kids off to school. But she says law is “unforgiving”.

As a judge presiding over family law cases, she often sees the worst of humanity: people can be really cruel, and when there is domestic violence she describes it as the “stuff of nightmares”. “You have to be able to switch off, otherwise you would not sleep at night,” she says. She tells young women not to see their gender as an inhibitor: “Focus on being the best you can be and doors will open for you. If you focus on what is holding you back, then that is a distraction. Don’t worry about what everyone else is doing, it is not a competition.”

The Public Defender

When Lizzie McLaughlin, 43, arrived at Sydney Law School, a lecturer breezily advised students to look left and right. Chances are, they were told, they were sitting next to either a future judge or MP. For McLaughlin, from country NSW, it was an eye-rolling moment. Since then, she has met plenty of judges as an associate to a High Court judge, a criminal lawyer with the Aboriginal Legal Service, and at the Bar.

Now, as a public defender in Newcastle, she represents people who face criminal charges that include “the very worst of human behaviours”. Child sexual assault. Rape. Murder. A tough gig defending such dreadful crimes?

“No matter why someone is before the court, unless they can access quality legal representation, their participation in the criminal justice system is unfair and unjust,” she says. “There is generally a lot more behind the byline snapshot of someone’s ordinary crime. It doesn’t mean they warrant sympathy, but it means there is a human element to their experience and a real context for their offending that I think is really important to understand.”

McLaughlin suggests a lack of women at the higher levels in law is not only because of family challenges but because women are often more risk-averse than men and may perceive such challenges as insurmountable.

The birth of her children has sorted her priorities, but it hasn’t been easy. “There is a culture – mostly among men – at the Bar that when you meet someone you have to tell them you are working so hard you can barely sleep, function, see daylight,” she says. “It is alienating and dull. I don’t want to be like that.”

As for advice for the next generation: “Your career as a lawyer will be for 30-plus years. Take the time to develop your career at a pace that suits you and your life.” And don’t be afraid to reach out and talk to more senior lawyers about their careers.

Says McLaughlin: “Learning why they chose their path, and how they feel about it now can be really helpful when you are trying to find your way. Behind that fancy CV may be a person who has had the same struggles as you. They’ve just come out the other side.”

The Partner

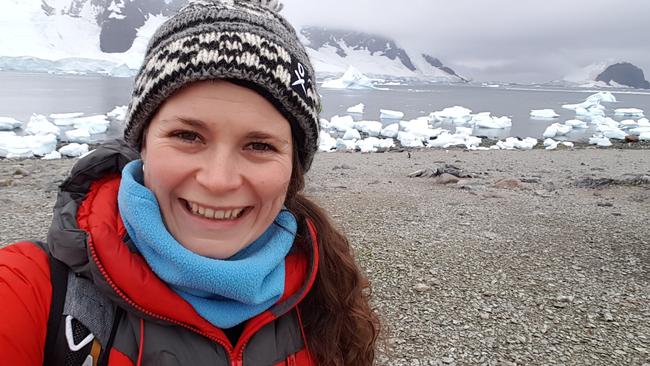

How do you make partner – the holy grail for lawyers in private practice – during a pandemic?

Julie Ma, 36, did not just have to contend with Covid-19, she was also returning from parental leave to her job at the global law firm Ashurst. It helped, she says, that her specialty of infrastructure law is sought after at a time when the federal government backs the sector in its road map out of lockdowns.

She also relied on her sponsor – a little like a mentor but one who vouches for you in promotion processes. “I was open about my aspirations about becoming a partner to my sponsor, and we always had an honest dialogue about my career – including how starting my family and growing it would fit in with my career aspirations and whether we could make that work,” she says. “I had the same conversations at home to make sure that I had the support there as well. That really helped.”

Ma grew up in Bankstown, the daughter of Vietnamese refugees. As a child, she didn’t necessarily dream of becoming a lawyer. The adults she knew worked in factories or ran small businesses. Her dad was a fishmonger. Her mum worked odd jobs. Her dream was to work in an office: “I thought that would be very cool.”

Ashurst’s Australian arm leads the way on gender balance among big law firms, but is still short of parity with just 63 female partners among the total of 165 partners. Ma blames this on the juggle of family and career. The idea of the boys club law firm is changing with generational shift, says Ma. If there has been a silver lining to Covid, it has shown that flexible arrangements work, although Ma argues changes were under way before the pandemic. She loves working in commercial practice but says it’s far from glamorous: “Suits makes it seem like the law is full of drama and expensive clothes. It’s not like that at all.”

The Public Prosecutor

On Sally Dowling’s first day at the NSW Bar, a senior barrister (now deceased) put his hand up her skirt. Four days later, he again made unwelcome physical contact. The only woman among 30 men at her chambers, she was shaken. Dowling, immediately reported the first incident to a senior barrister in chambers, and after the second incident she asked whether she should go to the police.

There were no more incidents but at the end of the year, when Dowling applied for a permanent position in those chambers, she missed out. She still wonders what impact her decision to speak up had on the selection process.

“That is the really insidious part of reporting sexual harassment in the workplace – you never really know what the repercussions may be,” says NSW’s first female Director of Public Prosecutions.

This month, the 52-year-old Dowling will introduce a formal sexual harassment policy for the ODPP.

But she also has other plans for her 10-year term, believing that there is always scope to continue to improve prosecution services.

Dowling’s path to law was unconventional. She left school in year 11, moved out of home and worked many odd jobs as a waitress, a singer, and a bookie’s clerk at a racecourse. She was by her admission “very strong willed, very independent, unafraid”.

“In hindsight, I realise how impatient I was to get out there and do the next thing,” she says. Those traits, she says, are at least part of the reason she believes she has been successful as a prosecutor. What did she learn from those early years? “There are class divisions in Australia and they are very real,” she says. “When you are at the bottom of the pile, the options are extremely limited. Even though I came from a middle-class background with tertiary educated parents, I was a young woman with no education, and that’s the bottom of the pile. It’s a very disempowered position.”

Dowling went back to education at TAFE and then law at the University of Sydney, and she is known for telling young people there are “many, many second chances”. Later, after she had a child – the first of three – she left the commercial Bar to work for the DPP and became the first prosecutor to work part-time as she raised her family with her barrister husband.

Over the years, Dowling has worked on some of the state’s most horrific crimes, including many murders and sexual assault prosecutions.

“The human spirit is incredibly resilient,” she says. “I have seen many victims of violent and degrading crimes who have undergone incredibly awful experiences and have emerged with dignity and respect for themselves.”

Vicarious trauma for lawyers is very real but Dowling says she has learnt to put boundaries around her practice: “I try not to take physical briefs home, and I don’t talk about the facts of my cases.”

The Magistrate

If Melbourne magistrate Abigail Burchill has one message for the next generation of legal practitioners, it is to not let your circumstances – or your fears – hold you back.

“The law is full of perfectionists,” she says. “We don’t see how many people we lose from the legal profession because we don’t make it more human.”

Burchill, 49, grew up in the Victorian country town of Mooroopna, a Dja Dja Wurrung Yorta Yorta woman at a time when expectations for Indigenous kids were low.

What’s worse than crushingly high expectations? “Low ones,” Burchill says. “It is so damaging.”

When she told teachers she dreamt of becoming a lawyer, she was urged to consider becoming a legal secretary instead.

Burchill attributes her ability to overcome her environment to her parents: “You should never underestimate the everyday leadership of parents.”

She admits to suffering imposter syndrome when she arrived at Melbourne Law School, where the attrition rate among Indigenous students was particularly high.

“I noticed how silently they would leave,” she recalls. “No lead-up, no talking. When you carry shame to your core, I think it really silences your ability to communicate and to say ‘This is how I feel at the moment’.”

She found going to the Bar equally difficult and recalls performance anxiety and long hours. At the time, she had three young children and while her husband was very supportive, the demands were gruelling.

“But I would do whatever I could to make my cases work, and when I was running my own cases I had endless energy,” she says. “I would think, ‘Other people have gone to bed, I won’t be doing that so I will know that point a little bit better’. I refused to fail. It was literally one foot in front of the other.”

Those years of struggle, she says, prepared her for her current role as a magistrate. She says empathy isn’t crucial on the bench, but it certainly helps when you are dealing with people who sometimes cry, who are sometimes defiant, and who can be so nervous they forget their own telephone number.

As a mentor to young people, Burchill draws on her memories as a country girl desperate to get to law school: “I say, ‘Where do you want to go and how can I get you there?’ I try to be like my mother, as practical as possible.”

The President

When Jacoba Brasch QC was starting out, she sometimes would be called “doll’, or “love” or “babe’. “It was designed to be dismissive and intimidate,” says the president of the Law Council of Australia.

She still hears that kind of casual sexism in the legal profession, directed not towards herself anymore but to her much younger female colleagues.

“We all need to get better at calling out such conduct,” she says, urging young women to use it as a motivator.

“When I first came to the Bar, a lot of things were passed off as ‘it’s just a joke’,” she says.

Now many firms and barristers’ chambers are “picking up their game”, but she acknowledges that there is still a power imbalance.

“A junior colleague calling out a senior colleague who is responsible for their career progression is a really tough gig,’’ she says.

Brasch is encouraged by the appointment of senior women to key roles, and by seeing so many talented younger women coming through the ranks.

One of the new breed is 24-year-old Kendra Turner, from Corrs Chambers Westgarth in Perth.

Turner was recently announced as the 2021 Young Australian Lawyer of the Year.

“We are now seeing more women in the law, and more open discourse around how we, in the legal profession, are going to retain senior women in leadership,” she says, citing conversations at her firm about promoting women, parental leave and flexibility.

Her advice? Consider what areas of law excite you and determine what pathways you can take to get you there.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout