Equality? Sure, but women can’t do it alone

We need family-friendly policies but organisations serious about tackling the gender gap need to get men on board.

When US business journalist Joann Lublin interviewed 86 executive mothers, and some of their daughters, about their experience juggling work and family, she was keen to find out if there had been a shift between the generations.

Acceptance of women in dual roles as caregivers and business leaders has increased, and so has the ability of women to manage their commitments, the former Wall Street Journal writer explains in her book, Power Moms, released earlier this year.

But that change hasn’t been as profound as expected: it’s still women who bear the brunt of the domestic load, along with the stress and guilt, which is “a troublesome sign that America must further improve its treatment of employed parents”, she finds.

The pandemic lockdowns, which initially sounded like a potential circuit-breaker for many women in the workforce, has added to the pressure on women, Lublin adds.

The double shift of paid and unpaid work has turned into the triple, with women often adding remote learning to their already packed schedule.

It’s the same in Australia, where data shows men have been helping during lockdown but women have been doing more – about an hour of extra unpaid work a day – and a growing number are leaving their jobs or study altogether.

But you can’t blame it all on the pandemic. The picture wasn’t great before Covid, and it is similar in many parts of the world, as Lublin’s research and other recent analysis makes clear.

While the advent of paid parental leave and flexibility has allowed many women to keep their jobs, the numbers in senior ranks has barely shifted, according to the authors of Glass Half Broken, released in June.

The rhetoric of women’s empowerment hasn’t delivered what many hoped, Harvard Business School academics Boris Groysberg and Colleen Ammerman write.

The reality of working lives for well-educated women in the US is still a long way short of an even playing field, they find, after interviewing graduating women and men as well as HBS alumni.

In the US, only 8.1 per cent of Fortune 500 chief executives are women.

The latest snapshot on women in leadership in Australia is equally bleak: just 10 female chief executives in the ASX 200 and only three out of 50 ASX 300 chief executive appointments in the past two years going to women, according to Chief Executive Women’s recently released Senior Executive Census.

The progress narrative that many women have absorbed is belied, the authors find, not just by what the research on gender barriers to advancement shows but also by what these women have experienced as their careers take shape.

Men are more likely to be promoted regardless of experience levels, and as women climb the ladder they face more pressure to prove they are capable.

An executive of a multinational food company told Ammerman and Groysberg she found it more difficult to be taken seriously and had to be more prepared than her male peers. Women of colour faced an even higher “burden of proof” and scrutiny in their careers.

The culprits, it seems, have a lot to do with enduring belief in a masculine ideal worker model, and that the most effective leaders are men, rather than in having kids.

While there are very few women in corporate leadership, many of this tiny group are mothers, Lublin points out.

A significant proportion of women in charge of major US corporations have children: 63 per cent of female chief executives of bigger business and 19 mothers out of 30 women steering companies in the S&P 500 index in March last year.

It’s a similar picture in Australia.

Yet organisations often assume women lack interest in progression because of long hours and lack of family friendly policies, Groysberg and Ammeran contend. Employers then encourage women (not men) to take parental leave or flex options, which push them further off the track and reinforce ideas they can’t handle the pressure. And of course, it leaves them quite literally holding the baby.

Investigating the tools to address the problem, they find that supportive managers who encourage and identify opportunities for employees make a big difference to women.

“Yet managers can only offer this kind of support if they strive to view employees through a lens that isn’t distorted by assumptions about women’s capability,” they write.

That also means skewering a trifecta of inaccurate beliefs: that women lack negotiation skills, are less confident than men and risk-averse. None of these is borne out in data, they point out.

The lack of confidence women are often labelled with is usually a response to being treated differently and held to higher standards in the first place. Managers need to get curious, not complacent, if they want to get the best out of their female employees.

It is true that trailblazing baby boomers typically foundered because they lacked female mentors with kids, involved husbands and supportive employers, Lublin’s research suggests.

But many Gen X women have found the same barriers, albeit with a bit more social acceptance.

And organisations largely have failed to encourage women or change the way they operate so women can progress. Instead many executive women have absorbed the blame when they can’t make headway on their own and feel ashamed of needing support.

There was no way we could change workplaces ourselves, says Beth Comstock, the first female vice chair of GE: “We needed to ask for more help and never should have felt guilty about it.”

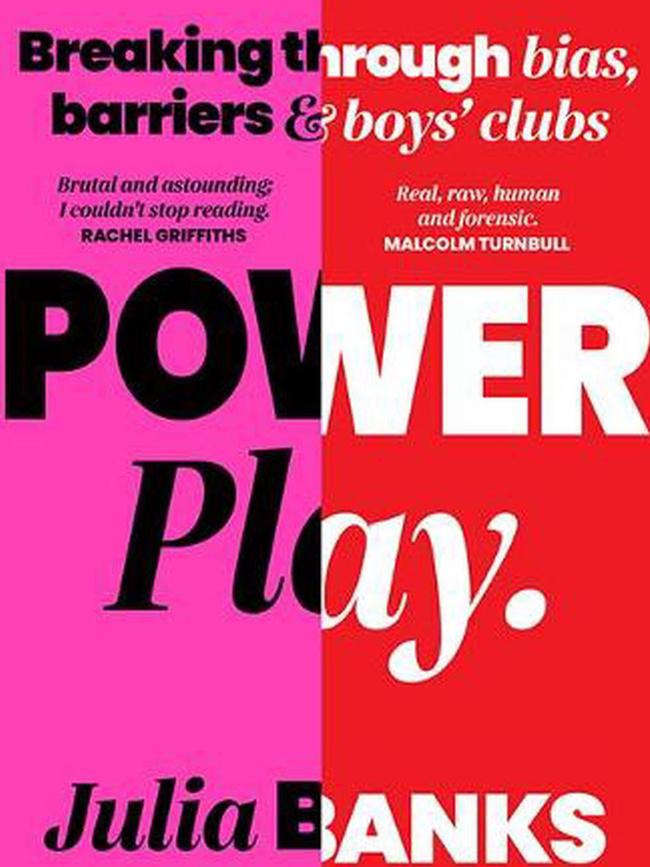

That’s a tricky line to walk, however, even for the more privileged female executives, as corporate lawyer and former MP Julia Banks reveals in her book Power Play.

Her experience shows that deeply entrenched assumptions can be a stumbling block to women in any industry. Outlining a range of incidents from both her corporate and political career, Banks makes it clear that there has been far too little real change in power dynamics. Speaking out about these issues can leave women exposed and facing real penalties, no matter what their rank.

Even though it appears that women in more well-paid and autonomous roles should in theory have a bit more ability to juggle family life, they often find they are “navigating new forms of subtle discrimination just as they are taking on increasingly challenging roles and new responsibilities”, say the authors of Glass Half Broken.

The higher a woman ascends, the more noticeable her difference from the masculine norm. Men who were OK working with women in general were less happy to have them as peers, one senior woman pointed out.

“I had anticipated that the affluence of Power Moms would allow then to deftly manage the conflicts between their work and family identities,” Lublin writes.

“The fact that many female executives still wrestle with these problems today reflects wider societal pressures affecting working moms in every kind of job.”

Work-family conflict can actually distract from barriers such as biased behaviours and attitudes. And as a result less time is then spent addressing discrimination, Ammerman and Groysberg suggest.

The default steps to address gender gaps can have unintended consequences and reflect more concern with symptoms and not the cause of the problem, these books reveal.

It also keeps the focus of the problem – and responsibility for solutions – on women and their behaviour or failure to conform rather than the bigger picture.

Documenting women’s experience in the workforce, emerging trends and the practical impact of policies, as these authors show, is essential and needs more attention.

The message from their analysis is that the answers to the continuing problems lie in asking both why and how sexism and bias operate, so that systemic change is effective for all women.

“We should no longer be satisfied with seeing individual women break through barriers – it’s time for glass-shattering organisations to clear away the sharp edges and shards that continue to keep women from achieving their full potential,” Ammerman and Groysberg conclude.

Old habits die hard, it seems, particularly when they support entrenched power structures.

-

Power Moms by Joann S. Lublin (HarperCollins)

Glass Half Broken by Colleen Ammerman and Boris Groysberg (HBR Press)

Power Play by Julia Banks (Hardie Grant)