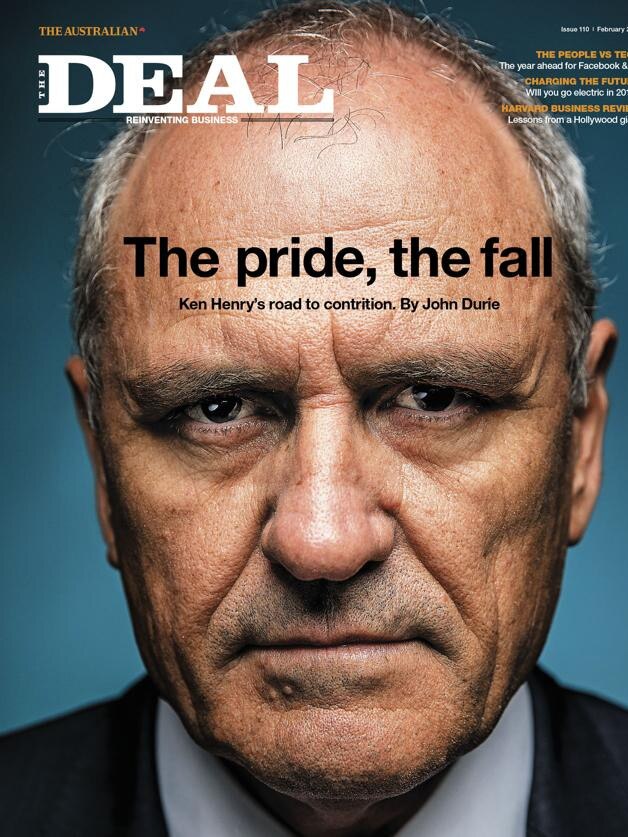

NAB chair Ken Henry on the fallout from the Hayne banking royal commission

The banking royal commission handed Ken Henry his biggest career challenge. He pushed back. But then it was too late.

Ken Henry is nothing if not staunch in his self-belief. His friends have often described him as the “great oak” – the stronger the wind blew, the harder he pushed back.

For months since a disastrous appearance before the Hayne banking royal commission last year, Henry was convinced that he had done nothing wrong, that his job was not in doubt and that he could get the bank back on track.

It was arguably his biggest miscalculation in a stellar career. In the end, his strength of mind and intellectual power were not enough to save him from one of the most devastating falls in corporate history.

MORE: I’ll prove the royal commission wrong, Henry vows

On February 7, one of our most eminent public servants-turned business leaders found himself delivering a humiliating and belated mea culpa on national television. Having announced hours earlier that he would leave the NAB board, Henry for the first time apologised to customers and citizens alike.

“We’re deeply sorry,” he told ABC’s 7.30, speaking for himself and his CEO Andrew Thorburn, who will leave at the end of the month. Henry will stay on until after a new CEO is chosen – unless of course that too proves a misreading and his tenure is cut short. However long he stays on at the NAB, it will be extraordinarily difficult for him to regain the position he has held in Australian public life.

On television, Henry seemed not just contrite but shell-shocked by the turn of events, conceding that the bank had an “absolute mountain to climb” to meet customer expectations.

It is clear from an exclusive interview he gave to The Deal just days before the banking report was issued that Henry had no inkling he was vulnerable. Commissioner Kenneth Hayne’s scathing comments were still under lock and key and the NAB chair was far from remorseful as he spoke from his home base in regional NSW.

Yes, he was shocked and disappointed at what had happened the previous November before Hayne. Much later as he stepped back, Henry would say he had relived his appearance countless times and wished he had done it differently. But in his interview with The Deal, he drew a distinction between his testimony and the public and media reaction, insisting it was the way he had been perceived that had disappointed him – not his own words.

And he declined to issue the mea culpa that even then could have softened his image, conceding only that he “could have done things differently” on that day at the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services. “My performance was characterised as pompous and arrogant,” he said. “Obviously I was disappointed with that because it certainly was not what I intended. I accept that’s how I came across and asked how that could be.”

‘Obviously I was disappointed with that because it certainly was not what I intended. I accept that’s how I came across and asked how that could be’

He sounded like a man who felt that the worst was over in terms of public humiliation, a testament perhaps to his extraordinary self-confidence. But on February 4, Hayne’s comments on the chair and CEO were incendiary.

Given a second chance to beat his breast, Henry once again declined to do so. The following day, he issued a statement rejecting Hayne’s interpretation. “Commissioner Hayne said I seemed unwilling to accept criticism of how the board had dealt with some of the issues raised by the commission. I am disappointed that the commissioner formed this view. I know that it is not so.”

The NAB chair was determined to stay in the job. The market considered him a “dead man walking”. On the night of February 5, he told The Deal: “I understand his [Hayne’s] scepticism but over time I will prove him wrong.” Less than 48 hours later he and Thorburn were gone. Now Henry said: “In our departures, we were hoping that we will contribute to a better industry that’s capable of delivering better outcomes for customers.”

For those who have long known Henry as one of Australia’s most eminent policy thinkers and as the long-serving Treasury chief, his reactions were not surprising. Over decades in Canberra, he proved a fearless policy maker – a player who had achieved great success serving both sides of politics. But others have recognised him as a man who despite great intellectual capacity and (refreshingly in business) willingness to speak his mind, sometimes lacked empathy with public opinion.

In this context, his comments made before his fall are revealing. In his January interview, Henry argued that the commission was a difficult forum in which to debate some complex issues facing the banking sector.

“I think there are issues I referred to in the appearance that are probably too difficult to talk about in that sort of environment,” he said. “I would have been better to introduce them in a different sort of forum. However, there was no other forum. The issues highlighted by the royal commission are real issues, they’re confronting issues and we in particular at NAB have to deal with them.”

After three years as chair of NAB and seven years on its board, there was a certain irony in being positioned as one of those unable to get the message: Henry was in fact a prime advocate for the commission to be set up.

Its establishment, he told The Deal in January, “was really a reflection on the place that the industry had got itself into, where the industry had lost trust and the industry needed to and needs to rebuild trust, and that starts with acceptance of the problem”.

He argued then that the key reason for a loss of trust is that banks had not paid attention to customer outcomes. Everyone in business acknowledged the need to keep customers happy, he said, but he wondered how much time they spend actually doing so.

“How much time do the directors on the boards of these companies actually spend out in the communities engaging with customers, hearing from them what good and bad things are happening and what products they need?” he said.

“I thought we had to have the royal commission to put the spotlight on customer outcomes and from that we could respond, and by responding rebuild trust with the community.”

And in a comment, now heavy with irony he told The Deal that the value of the royal commission now depended on how the banks responded “ because if the banks just say we have done all that is needed, then questions will be raised. “I never regretted – not for a moment – encouraging people to bring on the royal commission. I think it is absolutely what was needed. I think the industry, all the elements, had to come to a public forum and explain what they’re doing, why they’re doing it and what was their purpose, and the commission provided that forum.

“I welcome the scrutiny. We are in the spotlight and I’d like to think at NAB we are not frozen like a rabbit but are 12 months into a program of making the bank simpler.

“Too often the voice of the customer has been missing from our decision-making. And too often we have been prepared to accept good intentions rather than hold ourselves to account for operating with the required degree of urgency, consistency and discipline. We have been reluctant to set exacting standards and have not moved quickly enough to address weaknesses when they were recognised.”

‘I never regretted – not for a moment – encouraging people to bring on the royal commission. I think it is absolutely what was needed’

Henry is confident that the public mood against banks and big business is changing: “I think the community is at that point now. People understand that’s where jobs come from. They understand that it’s business that collectively decides what cities look like, where towns are located.

“They understand that it’s business people who are making those decisions. The difficulty is that if we just say, ah look, everybody should be happy, [it’s not enough]. We’ve also got to hold ourselves responsible for all the bad things that happen or the occasions on which we don’t get it right.”

The public debate is also improving, he argues.

“I’ve lamented the decline of the quality of the public policy debate and the quality of the political argument probably more than any other business leader,” Henry says. “[But] I’m sensing a turning point. I think the negative political argument has run pretty dry. I’m very confident that the senior people in both major political parties understand very well that the best thing that they can do to advance the wellbeing of Australians is to create a policy environment in which business flourishes.”

He is a vocal supporter of the need for business people to engage in public debates and quotes a recent Edelman Trust Barometer, saying “nearly three-quarters of Australians want business leaders to play a stronger role in the discussions about the country’s future and I agree 100 per cent”.

Henry’s first career was in the public sector in the national capital where he rose to its most senior ranks. However he says now: “I don’t actually miss a lot about the place. I had 28 years in Canberra and think it was long enough. I’m still interested in the issues and I guess from time to time I like to sit down and engage with people. But it’s not a big issue for me.”

The roles – bank chair and Treasury chief – were different but similar: “As far as the issues or the breadth of the issues, the span of issues, there are a lot of similarities. The complexity of the jobs is the need to be able to influence without directing. Your currency is your ability to influence. The most difficult thing for a board is knowing when it can be comfortable that everything is going well and when it’s time to make a change.”

One of the key issues raised at the commission was NAB’s charging of fees for no service – a practice the board failed to stop and which has now landed NAB in court. Henry says he has often asked himself why it took so long for the board to act.

“At some stage in the past 3½ years the board should have jumped in and said: ‘Forget all this. This is what is happening; this is a business where every decision affects the life of every Australian.’ That was true of Treasury as well, and at Treasury as at NAB we are deeply conscious of that fact.”

In both roles, he says, “the frustration is not really being able to at any time on any issue fully explain to everybody why something is happening and why it makes sense. Things move at such a pace and the commentary on events moves at such a pace that every time I pick up a newspaper and read something I get frustrated. That’s a fact of life.”

He said social media had changed life in good and bad ways: “It’s increased the tempo of activity and probably robbed us of the opportunity for a period of deep reflection, but the upside is much greater transparency and we should welcome transparency. We have to get more adept at operating in this new environment because, whether we like it not, it’s here to stay.”

Henry’s final years at Treasury and as special adviser to the prime minister included the writing of two landmark reports on Asia and tax reform, both widely seen as first class. Yet both received a mixed response from government.

“I was disappointed that the [Asia] report was not embraced lock, stock and barrel but I still think it has been influential,” he says. “I’m not pessimistic about it and I think there is a huge, quite deep understanding of the importance of the Asian century to Australia.”

In his interview with The Deal, Henry was convinced that he could take the bank forward, and talked about the need not just for digital and fintech solutions for customer but face-to-face banking in regional areas.

“I’m very confident that customers and the community will expect and want to sit down with a banker and talk about their needs,” he said.

He talked too of the challenge for business leaders to be able to tell the complete story to their employees and customers.

Its ancient history now, but the public servant turned chair was surprised by the volume of material – an average 1200 pages of dense material – presented at each NAB board meeting. this is no time for board to reduce the time spent in that area. He reduced the board papers to 800 but the board met 21 times last year. compared to its usual schedule of 10 meetings. The chances are that that number will not be reduced any time soon.

Henry who found that a board position he thought would occupy him three days a week in fact became a full time job, has plenty of time now to reflect on whether if his self-belief had been tempered with a touch of humility and a better sense of public expectations, he might still be in the chair.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout