Housing prices will probably still rise, but at a slower pace

The timing is interesting, with the data showing that after a prolonged lockdown, Sydney and Melbourne – Australia’s largest property markets – are well and truly geared up for a late spring selling season.

The question then is, will the changes have much of an impact on markets? And if not, will lending be tightened further?

On October 6 the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority announced changes to the serviceability buffer it expects the banks to apply when assessing home loan applications.

This will impact the maximum borrowing capacity for different cohorts. In a normal market, the impact of these changes may be easier to predict. But this is no normal market.

We can see in the data that Australia’s largest auction markets are lighting up.

Melbourne has returned to Super Saturdays (days with more than 1000 auctions scheduled) and Sydney volumes have increased markedly. At the same time, we’re recording bullish clearance rates around the 90 per cent mark for most capital cities.

Transaction volumes are also gaining pace, particularly in Victoria where weekly sales volumes jumped 60 per cent at the start of October. That market in many ways is now running ahead of the easing of lockdown restrictions.

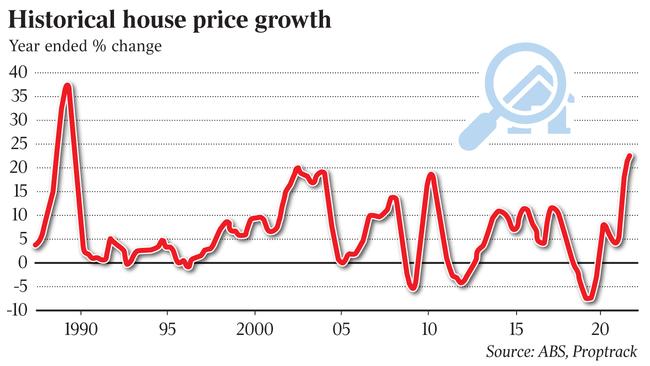

And then there’s prices, which nationally increased at the fastest rate in more than 30 years in the 12 months to September.

Although its early days, regulators may indeed need more substantial measures to cool Australia’s hot housing market.

APRA’s changes have started small and while buyers borrowing their maximum amount will no longer be able to reach the pricepoint they could previously, not everyone borrows at their maximum capacity.

The changes only reduce maximum borrowing capacity for most borrowers by around 5 per cent. And with vaccination thresholds being met, nationwide activity is clearly picking up as confidence is returns to the market.

The move from APRA appears to be somewhat pre-emptive – a shot across the bow to lenders to rein in high debt-to-income loans as restrictions ease.

Recently the Council of Financial Regulators warned on the need for lending standards to be upheld, citing signs of “increased risk taking” appearing in mortgage lending.

Housing debt-to-income ratios are at record highs for owner occupiers. The latest APRA data showed 22 per cent of new loans originated with a debt-to-income ratio greater than six times through the June quarter; and housing credit is growing at a three-month annualised pace of 8.1 per cent, outpacing income growth.

Much of what happens next will lie with the ongoing availability of credit.

The light-touch approach leaves the door open for APRA to bring in more complex tightening measures. They’ll do that if credit growth continues to outpace income growth, and fails to slow as borders reopen, discretionary spending is diverted elsewhere, and enforced savings taper as life returns to normal.

For those wondering what further macroprudential measures could look like, the Reserve Bank recently took a look at what’s being used abroad.

Naturally there is a fine line for the regulator to tread given the strong links between household consumption, the largest component of GDP, and household wealth in maintaining the post-pandemic economic recovery.

Rate cuts and resultant record lows in mortgage rates have been the key to credit growth and the boom in house prices. But rates are not going any lower and the availability of credit is beginning to tighten at the margins.

For owner-occupiers mortgage rates on new loans fell from around 3.2 per cent in February 2020 to 2.36 per cent now. So, with the same monthly principal and interest payment over 25 years, you can borrow roughly 10 per cent more money.

However, according to Proptrack since February 2020 dwelling prices across Australian capital cities have increased 21 per cent; for houses that figure is 26 per cent. Hence, the benefit of lower mortgage rates is largely spent for buyers (with the exception of existing owners). With the benefit of lower rates now largely baked into prices, and no commensurate pick up in incomes, affordability is deteriorating.

Further, mortgage rates have bottomed and as deposits taper and bank funding costs rise, higher fixed mortgage rates may trickle through next year.

Then there’s discretionary spending. As restrictions lift in NSW and Victoria, and borders reopen, people will be back to spending on eating out, holidays and entertainment. And on top of this you have APRA’s latest move, which should slow credit growth and housing market momentum at the margins.

All told, the cooling of double-digit price growth and a moderation in market activity seems inevitable. And any further changes that affect the availability of credit would further shift market dynamics. However, with growth gathering pace from its pandemic-induced dip, a resumption in international migration impending and rates remaining low, activity is likely to remain strong for now, albeit with prices growing at a slower pace.

Eleanor Creagh is a senior economist with REA Group.

This month the financial regulator made a much-anticipated move to slow the housing market.