The history of Australian housing shows our pursuit of lifestyle

Greek, Italian and other immigrants who flooded into Australia in the post-war era changed the way our houses are designed – to this day. What’s in store for the future?

It is said we Australians are united by a common belief in the notion of a fair go. And that may well be so. But there is something else that unites us, that drives consumer behaviour, that is evident in all communities across the continent. And that is the pursuit of, the penchant for, lifestyle.

The rise of suburbia

The way we live is important to Australians. It was the pursuit of lifestyle that prompted the great migration to suburbia from the 1880s onwards. This was enabled by the roll out of the railway and tramway network. It was an easy calculation for federation Australians: the cramped and congested inner city or the light and space of suburbia.

By the 1930s, AV Jennings in Melbourne and counterparts in other states conceptualised, and delivered, the Australian dream: the quarter-acre block with three-bedroom brick veneer.

In Victoria, the State Housing Commission (and counterparts in other states) developed cheaper versions of this “dream” to deliver houses in a post-war austerity model.

These weatherboard and iron houses replete with outdoor lavatory and laundry (then called a wash house) sprang up in housing estates in the outer suburbs. Others were developed in regional cities and towns in the late 1940s and 1950s.

To the post-war generation this was indeed a dream: it was social housing on a grand scale that aligned with core values of the Australian people.

Gentrification movement

The inner city fell into disrepair and disfavour after the war. Terrace houses from the 1880s by then were regarded as dark and cramped.

By the 1970s, a rejuvenation and gentrification movement surfaced in places like Melbourne’s Carlton and Sydney’s Balmain.

English terrace houses were made over and improved: lino was removed; seagrass matting installed. Kitchens were modernised with Laminex benchtops in swish burnt orange and a brooding mission brown. And here’s the best part: roses and rhododendrons were removed from tiny front gardens and patriotic Tasmanian blue gum (saplings) were planted.

Today, of course, we’re far more worldly, more knowing, more sophisticated in our tastes and lifestyle preferences. And while we are indeed all of these things, and it shows in our housing preferences, the way we live has fundamentally changed and, on average at least, we’re richer.

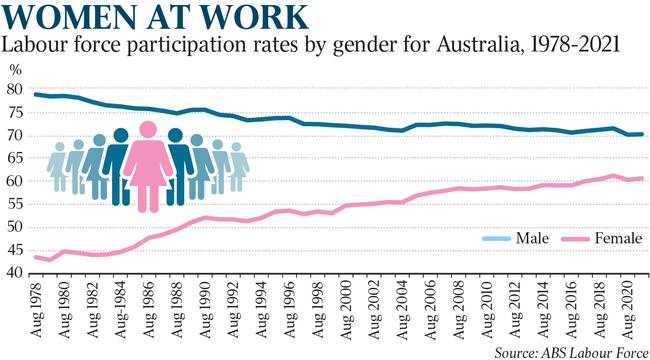

The housing required to meet, and exceed, the expectations of the post-war austerity generation was basic by today’s standards. Not only are modern Australians richer than those of the mid-20th century but the way we organise daily life has changed, including who engages with the workforce.

The return of women to the workforce from the 1970s onwards injected net additional financial capacity directly into the arteries of the family home.

The kitchen-family room

Working mothers immediately reorganised the family home: out with a separate kitchen and lounge room; in with a single glorious all-in kitchen-family room.

The inclusion of an island bench was essential in enabling the cook to simultaneously prepare a meal, watch television and engage in conversation with kids and/or guests.

And the styling is kinda cool too. Island benches look a lot like Houston’s Mission Control and especially when teamed with tech-blinking (European) oven gadgetry positioned high on the wall behind.

The epicentre of the home has shifted from the good room at the front to the newly evolved kitchen-family room at the rear. There were rumblings both before, and after, but this seismic shift took effect in the 1980s.

Women returning to or remaining in the workforce was the greatest single demographic and cultural shift to have impacted the configuration of the Australian home in the late 20th century.

But this movement, this megatrend, was given a bit of a kick-along by another trend pushing in the same direction.

Mediterranean influences

Enter stage left Greek, Italian and other immigrants who flooded into Australia in the post-war era. This cohort of workers, of doers, of labourers, worked hard, sacrificed, and measured their success by the homes they bought (often called Casa Mia) and by the success of their kids (my son the doctor, my daughter the lawyer).

And while the new migrants bought into the Aussie ideal of the pursuit of lifestyle through housing, I suspect they were puzzled by the product then on offer.

Surely when these migrants arrived in Sydney and Melbourne they wondered: “What the hell are those Australians doing living in an English house; they have a Mediterranean climate, even in Melbourne; they should have indoor-outdoor living.”

And the Australians, ever interested in anything that promises a better lifestyle, responded positively: “Actually, mate, you’re right … let’s change the way we live right across the Australian continent.”

And that is the story of how the epicentre of modern Australian life, the “kitchen-family room with outdoor alfresco” was conceived. And ever since then – say, from the 1990s – the Australian home, whether modest or grand, has been based on this simple but effective lifestyle layout.

Indeed so influential were the Mediterraneans in reimagining the Australian home that we nicked their terminology. The back veranda, a close but outdoor confrere of the kitchen-family room, has recently gone up-market and now will only respond – like pop stars Beyonce and Madonna – to a single name, “alfresco”.

In fact alfresco at the rear nicely balances portico at the front, don’t you think?

Our cherrypicking culture

The point I am making is that we Australians have built an extraordinarily absorbent culture.

We cherrypick bits and pieces from arriving immigrants. It might take a few years but eventually we work out what will and what will not deliver a better lifestyle.

There is another way to look at this and that is to say that we Australians are still a tad colonial in our thinking. We are mightily impressed by styling and accoutrement that signals a global worldliness. Interior designed Point Piper kitchens, for example, are universally Milanesque.

The Americans on the other hand are less absorbent; migrants there, I think, are more likely to be Americanised.

Travel and worldliness are highly valued attributes in remote colonial societies like Australia and New Zealand. (And which is why the border closures have caused such anxiety; we feel like we’ve been plunged back into the 1950s.)

And so we Australians design and decorate our homes in ways that reflect our core values – the relentless pursuit of lifestyle – and we’re prepared to alter, amend, even uproot, the way we live if we think there’s a better alternative.

Sell your suburban home and buy an inner-city apartment. Move from cold Melbourne to sunny Queensland as long as the move showcases a superior, freer, sunnier, beach-sophisticate lifestyle.

No point spending a motza on a Noosa Sound property if it looks like something you’d buy in Woollahra or South Yarra. It’s gotta have its own look, its own style; something that encapsulates what is unique about the location: water outlook, glamorous indoor-outdoor living, swaying palm trees. You know the look.

Megatrends at work

In the grand sweep of the evolution of Australian housing, and the demographic forces that have shaped our preferences, it is evident that female workforce participation and immigration have been tectonic forces. And they still prevail as does the Australian penchant for lifestyle and for showcasing worldliness.

But this raises the question of why the Australians so readily adopted the concept of indoor-outdoor living. Although I think a more pertinent question is, why did it take the Australians so long to reimagine the layout of the home.

Interestingly, in the regions, the stark Georgian homesteads of Tassie’s farmlands acquired shaded verandas by the time they surfaced on Yass sheep properties.

In Australian cities the only concession from the English bungalow to the local environment was the addition of land in the form of the quarter-acre block. And that model only worked because of the concurrent development of the motor car.

The point I am making is that the property industry can prosper by tweaking products and pricing here and there, but it is the megatrends that determine overall prosperity. And those megatrends include the unshakeable fact that Australian consumer preferences favour the relentless pursuit of lifestyle (and of showcasing worldliness).

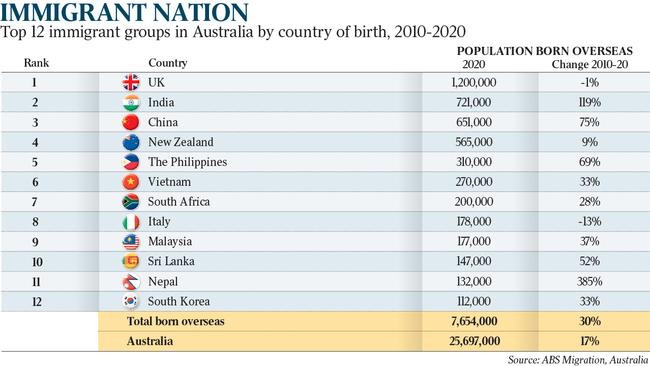

Another driver is the fact that 30 per cent of the Australian population was born overseas. This proportion for America is 15 per cent. For Canada it is 21 per cent. For New Zealand it is 22 per cent. In China it is 0.1 per cent. Despite being remote we’re subjected to more “cultural influences” than other countries of a similar scale. And it’s reflected in our housing.

What of the future?

The question I have is this: if the Greeks and the Italians so shaped Australian housing, and styling, from the late 20th century onwards, what will be the influences of more recent migrants from India, China and The Philippines on the housing market in the post-Covid 2020s?

And just as women remaining in the workforce changed the layout of the family home then something like working from home could also be a powerful force in reconfiguring the way we live.

The housing industry is a key driver of Australian prosperity. But it’s hardly a static business. Its influences – immigrants, social behaviour, household prosperity – are constantly evolving. And which is why I say that sometimes you need to stand back, to view the grand sweep of history, in order to identify the trends likely to shape the market.

And which is why I am working on a similar piece on the house of the future which I will publish in November.

Bernard Salt is executive director of The Demographics Group; research by data scientist Hari Hara Priya Kannan

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout