Census shows Australia’s capacity to build better communities

It’s not property that makes Australia a great country, it’s our capacity to give to create an even better nation

In 1965 the American pop group The Byrds had a hit on their hands with Turn! Turn! Turn! (To Everything There is a Season) the lyrics of which explained, among other things, “there is a time to plant, a time to reap … there is time for every purpose under heaven”.

Personally, I think The Byrds could have extended their observations about the seasons of life to include “a time to give, a time to receive”.

Perhaps if they had access to the Australian Census this line might have made it to their hit song.

I am interested in the rhythm of the life cycle and how external forces shape our predisposition to invest in our future security and/or to simply invest by giving back to the community.

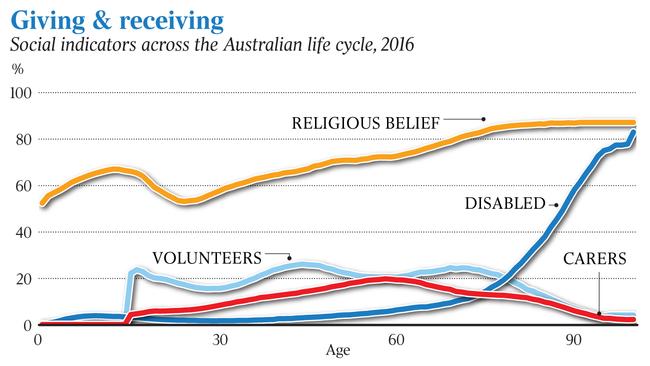

I think the time in the Australian life cycle to invest and reap is evident in social indicators in the 2016 Census. (New 2021 Census figures will be published in November 2022. My experience with censuses is that these social indicators do not change dramatically from one Census to the next.)

A time to believe

One of the questions the ABS asks in the Census deals with religious affiliation. About two-thirds of Australians declare religious affiliation. And it applies to the entire population including babies through parents who attribute an affiliation.

When belief, and non-belief, are tracked across the life cycle it rises and falls. Religious affiliation peaks at 16 when teenagers are living at home, attending a denominational school. Soon after leaving home, however, belief is apt to subside and then reaches a low point at age 23.

So, in life cycle terms, religious affiliation reaches a nadir in the early 20s. And the reasons are clear enough. At this time in life Australians don’t usually have kids. Their parents and grandparents are still alive. There are better things to do than invest time and effort into “belief.”

But thereafter comes a shift in thinking. Kids arrive and decisions are made about schooling. As the end-of-life approaches Australians are, based on Census figures, more likely to register religious affiliation.

In one sense “belief” is an investment in the future. Indeed it’s a bit like buying a house or investing in superannuation; it promises security. In the early 20s the need for security seems unnecessary but later in life such matters become more important. The fascinating thing about the Australian Census is that it is possible to cross tabulate datasets.

If 67 per cent of Australians declare religious affiliation (ie prepared to sacrifice now for the prospect of later reward), then where does this proportion peak among our 100 largest cities?

The answer, my friends, is Griffith where the proportion of believers tops 84 per cent. This is followed by Parkes (82 per cent), Dubbo (80 per cent) and Tamworth (77 per cent) (see graphic 2).

At other end of the spectrum are communities where religious affiliation is less important, namely Broome and Yanchep (both 54 per cent).

I wonder whether there is a fundamental difference in attitudes towards long-term saving and investment expectations in Griffith and Broome?

A time to volunteer

If there is a time to invest and time to reap, as suggested by The Byrds, then this is evident in the Census question around volunteering. Australians aged 15+ were asked if they volunteered over the last month; 21 per cent reported in the affirmative.

So, how does the Australian propensity to invest in the community by volunteering rise and fall across the life cycle?

This proportion kicks off with a bang at 16 by contributing to school, or to sport, or to gain experience for a CV. It then drops to a low point at age 30 before peaking again at 44, which aligns with parental involvement in kid’s schooling, for example, tuck shop or Little Athletics duty.

Then it reaches another low point at 60 before peaking again at 64, which aligns with retirement activity.

Giving back to the community via volunteering peaks when the community to which Australians are connected, requires support.

Another way of looking at this is to say that the more connected communities garner the most volunteers. And again this indicator can be tracked across Australian cities.

Of Australia’s 100 cities with more than 10,000 residents, the highest proportion of volunteers — implying community connectedness and strength — is Horsham where 33 per cent of adults volunteer. This is followed by Esperance (31 per cent) and Armidale (30 per cent).

Cities least likely to volunteer comprise new communities where both the household’s partners are likely to work full-time such as Melton (14 per cent) and Yanchep (16 per cent). I also suspect that migrant communities “volunteer” through extended family support which is an activity that is not necessarily picked up by the Census.

A time to care

Another question from the Census asks if anyone aged 15+ in the household provided unpaid assistance to a person with a disability.

Here again is evidence of Australians giving to, and thus investing in, their local community.

Across Australia, 12 per cent of the adult population reported providing unpaid care to others. (Not as a one-off because they were incapacitated but because of a disability.)

What I admire about this 12 per cent of our compatriot population is that this proportion rises unerringly and purposefully across the late teenage years, throughout the partnering 20s, before peaking at the age of 59.

Those most likely to deliver unpaid care (as defined) are our late 50-somethings.

But more than that I admire 20-somethings who are prepared to help a family member — a parent or a sibling — without paid support. It is the stuff that holds us together, the unsung heroes, the doers, the givers, who put the needs of others before themselves.

And why does this care-curve subside after 59? Because I suspect this most commonly relates to a 50-something caring for an 80-something parent (or in-law) who eventually dies. Perhaps this curve can be used as evidence for the provision of targeted in-home care and support.

This curve also reminds home builders of the need to build in the capacity to allow for the later possibility of disability. This might include wider hallways and doorways and more open bathrooms that can be modified over time.

A time to support

And then we come to the Census question that asks whether anyone in the household has a disability relating to a core activity such as mobility.

What strikes me about this response across the life cycle is the fact that disability is present in every year of the life cycle including 2 per cent at age 30.

But of course the disability rate rises over time afflicting 6 per cent at 60 and 21 per cent at 80. By the age of 90 almost 60 per cent of the population reports some form of disability.

In one sense our increased life expectancy delivers a longer life and a better quality of life.

But there are challenges with longevity and these especially apply to the frail elderly who cluster in some cities and suburbs (for example, via nursing homes).

Whereas 6 per cent of all Australians report some form of disability this proportion rises to 11 per cent in each of the cities of Maryborough (Queensland), Kempsey and Hervey Bay.

At the other end of the ranking of the 100 largest cities in Australia, the proportion of the population with a disability is just 1 per cent in Karratha, 2 per cent in Port Hedland and 3 per cent in Broome. These communities are skewed towards the young, due to the presence of mining which requires a youthful workforce.

A time to build

Australians are great investors, not just in housing but in families and in communities. Not all Australians, and not at all times throughout the life cycle. However enough Australian invest home ownership to support a vibrant housing industry.

But there is another investment that I think is worthy of amplification and of a better understanding.

And that is our preparedness to give, to sacrifice, to submit ourselves to the pursuit of something better: be that a community that works, a family that is supportive and inclusive, or (for some) the ideas associated with religious affiliation.

In one sense we’re all believers. It’s really just a question of what we believe in. For the majority of Australians I would have said we believe in property, in housing, in home improvement. And I am sure for many this is the case.

But for others there is belief in doing the right thing, in making a contribution, in quietly and stoically helping a family member with a disability throughout your own fit and healthy 20s.

That single insight, that hidden gem uncovered by the Census, shows why, at this post-lockdown time especially, we all should have faith in the future of Australia.

It’s not property that makes us a great nation, it’s our capacity to give and to build better communities and to create an even better nation.

Bernard Salt is executive director of The demographics Group; research by Hari Hara Priya Kannan

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout