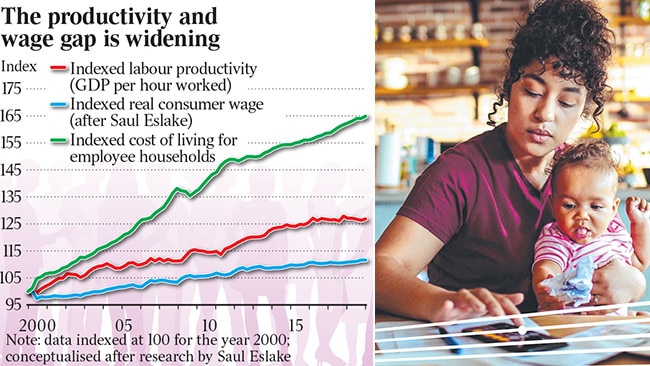

Our first chart (above) looks at labour productivity and wages. Productivity is what the worker gives the employer and wages is what the employer gives the worker in return. For a long time, these two curves grew in unison. When workers created more gross domestic product (GDP) in Australian fields, factories and offices, they saw their wages grow at a similar rate.

That changed in recent decades as a productivity-wage gap emerged. We only see data for the past two decades here (rebased to 100 for the year 2000) but the growing disparity between what workers produce and the compensation they receive is obvious. Aussie workers produce more wealth than ever before but don’t get a fair slice of the pie. Simultaneously, the cost of living for the average employee household shot through the roof.

While some luxuries of life (tech gadgets) became cheaper, most essentials of life (housing, schooling) became much more expensive.

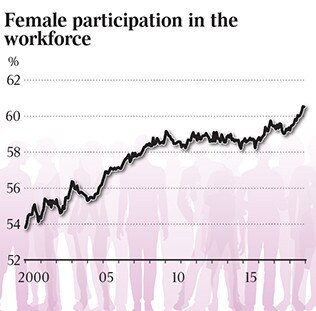

Our second chart shows how families tried to keep pace. Many families added another income to the household by ensuring the mother returned to the workforce soon after childbirth.

By adding a part-time or even a full-time income to the family budget, the increased cost of living could be forgotten — at least for a bit. Households had more money to spend, which was great for the economy as the additional female incomes swiftly went back into circulation.

It is of course impossible to say what share of the increased number of female workers was due to economic necessity and what was a result of female empowerment. The two narratives get entangled anyway as people make sense of their lives. Am I going back to work because my family can’t afford the house or because I am a modern independent woman wanting to showcase my skills and talents in the workforce? We are arguably better off psychologically when we focus on the empowerment story.

As we saw more dual-income families, especially in the lower and middle classes, the time parents were able to spend with their kids declined. This forced families to spend at least some of their additional income on childcare and household related tasks (that were previously done without remuneration by the women).

The big squeeze

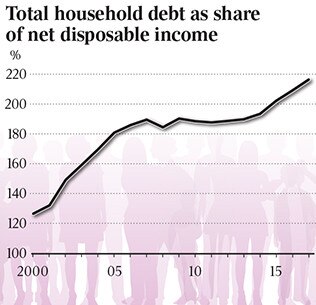

Our third chart shows how the middle class reacted as the economic squeeze continued and even two income households couldn’t keep pace with growing expenses.

Australians reacted by borrowing more. The debt of our average household, measured in relation to the disposable income, almost doubled in less than two decades. This money largely went towards housing needs. The basic expenditure category of housing has become a luxury commodity for many Australians.

Our local middle-class family now is more economically productive than ever before, has both parents in employment, spends less time with their kids and holds more debt, forcing them to work longer hours just to get by.

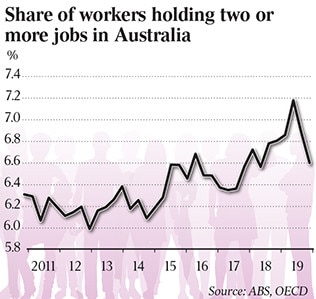

Our fourth and final slide shows that still more can be squeezed out of low-income households. We see that more Australians than ever before hold at least two jobs. At its peak, in December 2018, one in 12 Australian workers held more than one job. That meant that more than one million Australian workers had more than one employer. These second (and third) jobs overwhelmingly weren’t inspiring side-hustles or passion projects, but low-skilled and low-paid jobs.

As bad as that development is, it makes sense. If a household doesn’t earn enough to provide a somewhat decent life with two jobs, one of the adults will take on a second job. These multi-job employees are working themselves to death in order to get by. We must not allow this to become the norm in Australia. The US showed that this is poison for social cohesion in a country.

So, what does that leave us with? We’ve seen that a growing number of Australian households are economically squeezed, and our famed liveability is but a distant fantasy for many. It must be our collective ambition to ensure (at the very least) that every family with two full-time income earners can live in comfort.

Better jobs

We create more jobs than ever before in Australia. But it’s not just the number of jobs that matters.

Between our last two censuses (2011 to 2016) half of the new jobs we created were highly skilled (and decently paid) jobs. We also created tons of low-skilled and unskilled jobs. What we didn’t add were middle-skilled jobs (this category made up only 1 per cent of all net new jobs).

What do middle-skill workers need to do when their job category isn’t going anywhere?

They could invest time (and money) to upskill and get ready for a higher-skilled job. Great idea in theory, but often not practical, as the worker’s hometown simply might not provide any high-skilled employment opportunities. In lieu of high and middle-skilled jobs the middle-skill worker is forced to take a low-skilled job and receive an income below their middle-skill earning potential.

As a nation we are not using the talents of our workers in an optimal way. That’s a tragedy.

I think the best thing we can do to improve the lot of the Australian middle class is a massive infrastructure spending program. The construction industry relies heavily on middle-skilled workers.

Spending on infrastructure will help our middle class more than any type of financial welfare program ever could. It’s also exactly what our cities and regions need since for two decades infrastructure growth didn’t keep pace with population growth.

To prepare our nation for such an infrastructure boom we must invest heavily in our TAFE system now to prepare the middle-skilled workers of tomorrow. A wise government upgrades TAFE now and in parallel lines up a huge infrastructure program. This is the best way to un-squeeze the Australian middle class.

Simon Kuestenmacher is co-founder and director at The Demographics Group

For an increasing number of people in the Australian middle class (let alone low-income workers), home ownership feels way out of reach. Let’s explore four charts detailing why our middle class feels so squeezed and so left behind.