Two stories last week show why education journalism informed by the interests of students rather than the self-interest of politicians or teachers is critical.

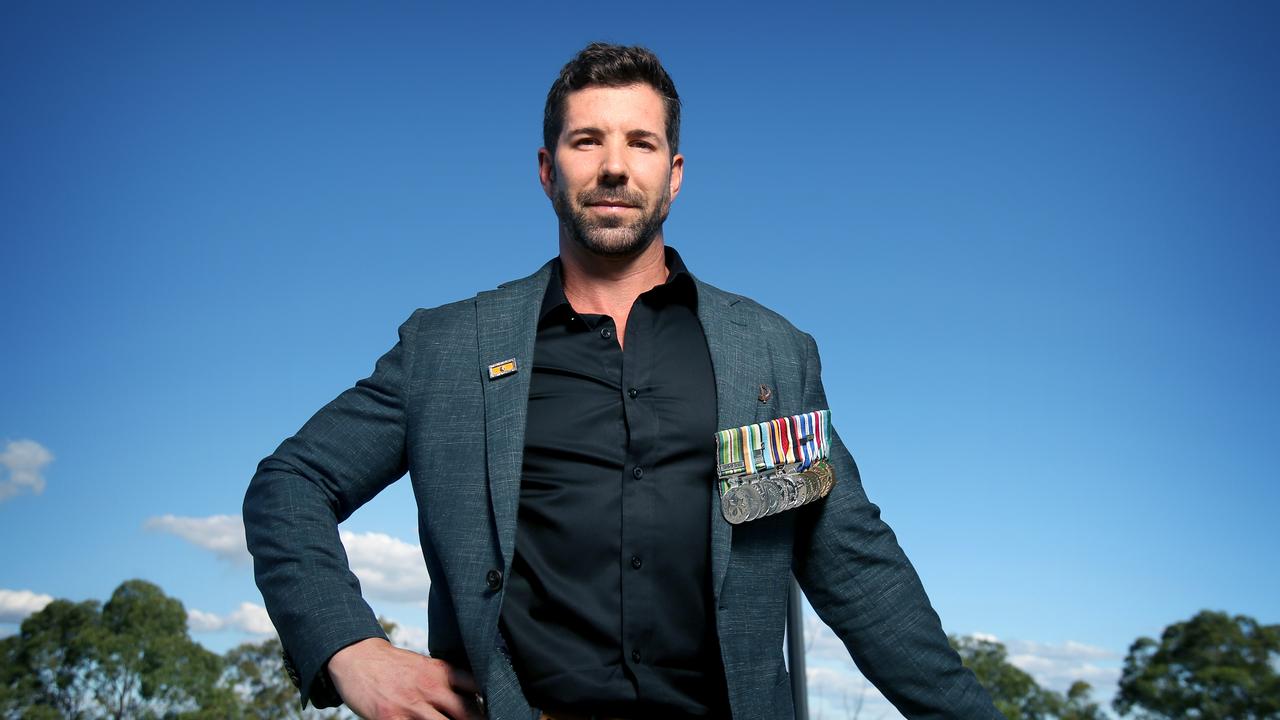

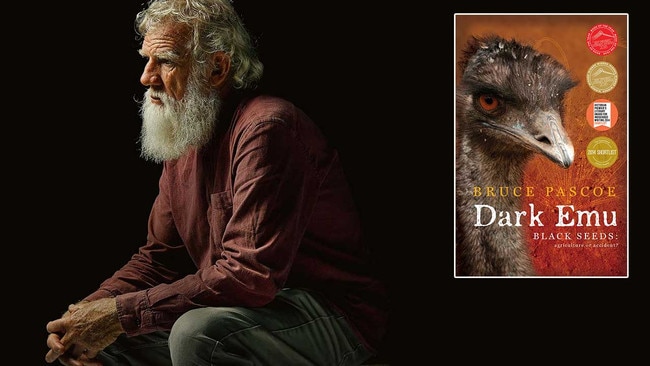

A story on Wednesday highlighted again the poor performance of Australian school students in international testing. It came in the middle of a heated media debate about Bruce Pascoe’s book Dark Emu, now being studied in schools despite its contentious thesis and disputes about the author’s aboriginality.

Senior members of all three tribes Pascoe claims he is descended from deny he is in any way linked to them. Several Aboriginal leaders reject the book’s descriptions of an Aboriginal farm culture and villages of up to 1000 people in stone huts before white settlement. The Saturday Paper’s Rick Morton countered with an unnamed Aboriginal source last Saturday week defending Pascoe and his claims.

It’s a great media stoush but surely the book’s claims and Pascoe’s identity need to be resolved for it to be suitable for school geography lessons.

READ MORE: Historical doubts ignored | Truth at the heart of indigenous voice | The man behind Dark Emu | Important questions need to be answered

The academic left regularly cites cultural appropriation to deplatform authors, so Pascoe certainly needed Aboriginal identity to ensure the success of a book that has already sold 100,000 copies. Yet a detailed 5500-word genealogical study by Perth writer Jan Campbell with 75 original documents suggests Pascoe’s ancestors are English. A fact check by a professional genealogist is available on the website Australian History — Truth Matters.

I have no problem with reconsidering Aboriginal life before European settlement. Much modern imagery about that life is based on our understanding of desert tribes rather than, for example, the Brewarrina, NSW, tribes who used fish traps or northern saltwater people with abundant sources of food.

Pascoe’s work has not sprung from an intellectual vacuum. The Conversation website in June 2018 traced the many books that have reconsidered pre-settlement agricultural lifestyles going back to the work of Barbara York Main and W.K. Hancock in the 1970s, Eric Rolls in the 80s and Tim Flannery’s The Future Eaters in 1994. Particularly influential was Bill Grammage’s The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia in 2012.

This paper reported in May that Pascoe admits he borrowed heavily from Rupert Gerritsen’s 2008 book Australia and the Origins of Agriculture. Gerritsen’s brother Rolf, a professor of indigenous policy studies at Charles Darwin University, says “90 per cent of Bruce’s book is taken from my brother’s work”. Rupert, convicted over an attempted terrorist bombing in Perth in 1972, died in 2013 without academic success.

Aboriginal women Josephine Cashman and Jacinta Price raised crucial cultural issues when they spoke on the Bolt Report in separate interviews about the eurocentricity of Pascoe’s claims. Both women are proud of their hunter gatherer ancestry and dislike attempts to paint their forebears as farmers in the European mould.

As Price said last Wednesday, if any of Pascoe’s theories were true they would be referenced in some of the thousands of Dreaming stories that have kept Aboriginal people safely on this land since long before agriculture in Europe.

This is a perfectly legitimate field of academic and media discussion but why teach it as fact to schoolchildren? It sounds like curriculum activism to me.

As usual the educational left reduced the results to grumbles about government funding, teacher pay and class sizes. Labor tried to maintain the fiction the Coalition has cut education spending, when it is up tens of billions in real terms over a decade. The real problems are the curriculum, the teachers, the students and their parents.

The introduction of national requirements for teachers to report on indigenous, sustainability and Asian engagement criteria across the national curriculum has only worsened problems of curriculum clutter. Aboriginal leader Noel Pearson has shown another way with his support for direct instruction.

His Hope Vale school on Cape York shows what can be achieved by committed teachers, even in an underprivileged area where many parents cannot read or write and where English may not be the first language. Here teachers stand in front of class and drill spelling, sentence construction and times tables into children so that this knowledge has what education academic Kevin Donnelly calls “automaticity”.

Children are made to pronounce syllables and sound out words as they begin to read. The whole language reading method is rejected in favour of the phonics approach that has worked since reading started. Modern ideas of child-centred learning have no place here. The teacher is unambiguously in charge.

National education correspondent Rebecca Urban made a similar point last Wednesday. She quoted OECD education director Andreas Schleicher praising an English school “vilified for being the strictest in England”. After visiting Michaela Community School in northwest London Schleicher said positive discipline and direct instruction were “creating happy and confident pupils with outstanding outcomes”.

How many modern city homes are like those of Hope Vale if we are honest? How many middle-class capital city parents use an iPad loaded with cartoons as a child minder rather than read to their kids before bed time? How many children ever see their own parents reading a book?

Teachers complain that too many students come to school exhausted after too much time on devices. Pasi Stahlberg, Finnish professor of education at the University of NSW, wrote in The Sydney Morning Herald last Thursday that even Finland, the poster child of educational standards, was slipping in PISA rankings because young Finns were spending too much time on devices and getting too little sleep.

On the role of teacher training, Sydney University vice-chancellor Michael Spence gave the game away in 2012 saying on ABC Q&A, “(we know) that nobody is ready as a professional at the point at which they leave university … so a profession has to take a certain amount of responsibility for on-the-job training. (Our responsibility) is about teaching critical thinking.’’

This is unlike the teachers colleges of the past that turned out teachers equipped to stand in front of 30 children. The government should consider reversing the changes of Keating era education minister John Dawkins in 1987 and recreate the binary system of colleges of advanced education, including teachers colleges, outside the university sector. This paper at the time predicted the change would harm teaching and it has.

Governments should ensure we no longer accept teachers with ATARs below 50, and in some cases as low as 20, if we want to emulate the education culture that makes students thrive in Singapore and Shanghai.

Most of all education bureaucrats wanting to drive political change — such as the way we think of Aboriginal life before colonisation — need to be purged. We need equality of opportunity rather than the left’s equality of outcomes. Educators who think Google and a calculator make traditional education obsolete need to get out of the way.