Bruce Pascoe, the man behind Dark Emu

Academic conflict accidentally turned Bruce Pascoe into our most influential indigenous historian.

Bruce Pascoe likes to tell a good yarn, and one of his better ones concerns the time that his long-running conflict with academia accidentally turned him into our most influential indigenous historian. This was eight or nine years ago, not long after Pascoe began vehemently proclaiming that generations of Australians had been duped by their history books into the false belief that Aboriginal people were nothing more than spear-throwing nomads before white colonisers arrived here. In fact, he said, Aborigines cultivated crops, built large villages and devised sophisticated dams and aquaculture systems — achievements Australians were so ignorant of that the country was like “an innocent baby” with a paper bag over its head.

At the time he was lobbing these polemical bombs, Pascoe was best known as a writer of fiction and a publisher, pursuits he had subsidised over many decades by working variously as a tourist guide, dairy farmer and fencer. His broadsides against the history profession, he recalls, came to the attention of a group of academics in Canberra who were sufficiently concerned to invite him to an off-campus meeting at one of their homes. Pascoe remembers arriving there in his second-hand ute, having driven to the nation’s capital from his home four hours away in the remote Victorian town of Gipsy Point in East Gippsland. “They said, ‘Look, we don’t want you talking to our students about this stuff, because it’s wrong, it didn’t happen’,” he says. “‘You’re talking about agriculture, but that didn’t happen. Aboriginal people were hunter-gatherers’.”

Pascoe is hazy on the identity of these eminent professors, but remembers that they slapped him over the wrist with utmost civility. “Cup of tea, lovely conversation — nice people, actually. But when I left that meeting, I got in my old beaten-up ute, and I was furious.” He says he drove straight to a second-hand bookstore and plonked down $8 for a copy of the journals of 19th-century explorer Sir Thomas Mitchell, which he cracked open while sitting in the driver’s seat. There his eyes fell on Mitchell’s eyewitness account of Aboriginal villages in Queensland housing more than a thousand people, and “haycocks” of harvested seed-grass stretching for miles, drying in the sun to make flour for native bread. It was then he knew he had his next book. “I have to thank that group of academics,” he says wryly. Because without their intervention, he might never have written his one and only bestseller.

Pascoe’s slim tome, Dark Emu, first published in 2014 by a small non-profit press, has become the unlikeliest nonfiction hit in the country. Subtitled Black Seeds: Agriculture or Accident?, it has sold more than 100,000 copies, won Book of the Year at the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards and is coming soon to a classroom near you. In it, Pascoe argues that the true history of pre-colonial Australia was hidden away for more than 150 years. Not only did Aborigines invent democracy, pioneer humankind’s first complex fishing systems and bake the first loaf of bread, they were agriculturalists with skills superior to those of the white colonisers who took their land and despoiled it.

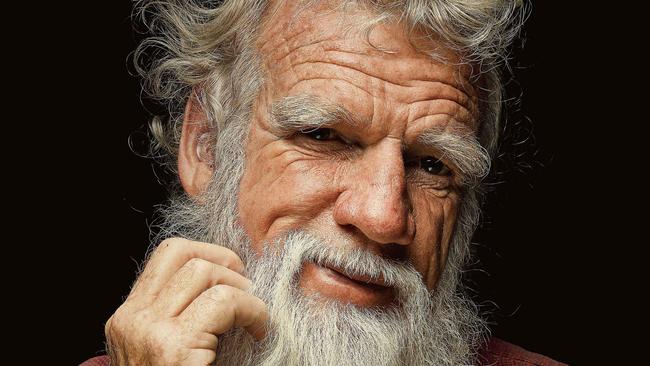

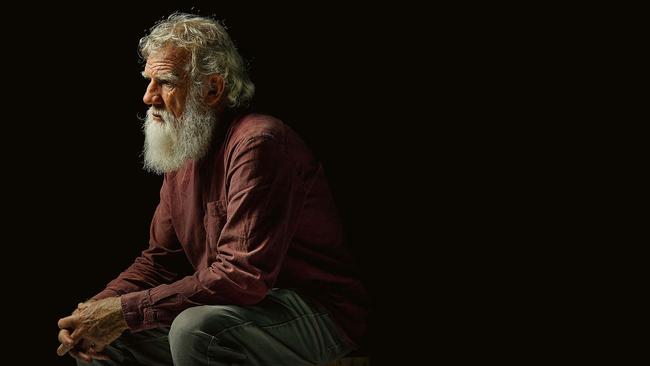

It’s a sweepingly revisionist view, one that still gets some eminent professors very hot under the collar. But it has so captured the public imagination that the book is now in its 28th printing and has launched Pascoe on a publicity tour without end, a white-bearded 72-year-old enjoying a late-life flush of fame and influence. His optimistic vision of indigenous culture as a balm for a world beset by ecological and political calamity has found a receptive audience among younger readers. The arc of his own life, from working-class whitefella to Aboriginal eminence, tells its own story of hidden history and racial reconciliation. Even some of the historians who contest the details of Dark Emu doff their hat to its author’s breakaway success.

“It’s a positive message that a lot of people want to hear, and Bruce is an Aboriginal man telling it,” says Ian McNiven, professor of indigenous archaeology at Monash University. “He’s an extraordinary looking man, he’s a great orator and a great writer… if you can turn a book like this into a bestseller in airport bookshops, more power to you.”

Pascoe himself embraces the success with his own peculiar mixture of self-deprecation and grand uplift. “I had a feeling this book would reach a wider audience,” he says. “It just goes to show that Australia is changing its mind about its own history — there’s a conversation going on, and people are using the book to open that conversation. There’s still a few dinosaurs about, but the kids in particular are all over it.”

When we first meet, Pascoe is sitting on a banquette inside the Sydney Opera House, preparing to deliver an address to a gathering of the Heritage Council. Five years after the release of Dark Emu its author is in constant demand at history conferences, literary festivals, indigenous gatherings and more specialised events such as the Lake Bolac Eel Festival in western Victoria. At the nearby Rainbow Serpent Festival in January he drew a crowd of admiring young alt-lifestylers taking a break from the doof. At rural gatherings he yarns with farmers about sustainable agriculture. More recently he’s become a fixture on the burgeoning “native cuisine” gourmet circuit, spreading the gospel about roast daisy yams and indigenous millet bread. “There’s a thirst for knowledge out there, so indigenous people who can talk about it are running around like cut cats servicing the other 97 per cent of the population,” he says, looking exhausted after a day spent talking to indigenous film students and meeting colleagues at the University of Technology Sydney, where he is a professor of indigenous studies. “But there’s no point grumbling about it. I hate to use a football analogy, but there’s a point in the game when the ball is in the air, the pack has formed underneath it and everyone knows whose moment it is to take it.”

Pascoe’s gift of the gab, both in person and on the page, is no small part of Dark Emu’s appeal. Not many historians have the vernacular gift to describe Melbourne’s founding father, John Batman, as a fraudster with “more angles than a map of New Guinea”. For tonight’s gig he’s dressed in dungarees, short-sleeved shirt and work boots, much the same outfit he wears while tending his 60ha farming block near Mallacoota, on the remote far eastern coast of Victoria. His flowing white beard and crinkly gaze complete the picture of a Whitmanesque bush elder dropped into the big smoke. Up at the podium, he’s both provocative and disarming, denouncing the mining industry’s “malicious” industrialising of the Burrup Peninsula in WA, then pleading for financial backing for indigenous farmers (“I’m beggin’ ya, seriously…”). Along the way he outlines his thesis in Dark Emu and his passionate case for indigenous Australians as the pioneers of human society.

“Aboriginal people, who invented government 120,000 years ago, decided that the worst thing they could do in a society was fight for land,” he asserts with typical brio. “[They] decided everybody would have a house, everybody would have enough to eat, everybody would take part in the culture.” We’re facing a pivotal moment of history, he tells the crowd. “We’ll think of this era of change in Australia and say: ‘This was the moment we changed our minds about our country; this is the moment that we became Australians’.”

It’s the evangelising of someone who experienceda late awakening to indigenous history, both the country’s and his own. Growing up in 1950s working-class Melbourne, Pascoe knew poverty but not much family lore. His father Alf — “a terrific carpenter but a terrible businessman” — earned such an erratic living that Pascoe can remember watching his mother at the kitchen table, divvying up her husband’s meagre wages right down to the last threepenny piece. In his fiction there’s a deep identification with society’s toilers and an equally deep distrust of bosses and the political class. Bricklaying was Pascoe’s first employment but his “infatuation with words” led him to Melbourne University and a job as a high school teacher in Mallacoota, which wasn’t even on the power grid back then. By his late 20s he was married with a daughter, Marnie, and had bought a home in Melbourne, determined to avoid the poverty he’d grown up in.

Today Pascoe can identify moments in his childhood when the hidden history of his family was briefly illuminated: the taunt of “nigger lips” at primary school; an indigenous woman remarking that “we know who your family are”. His mother’s brother sometimes alluded to their Aboriginal ancestry but Pascoe didn’t begin investigating it in earnest until he was in his early 30s, by which time his marriage was crumbling and he was attempting the financially perilous switch from teacher to writer. He had fallen for the woman he would spend most of his life with, Lyn Harwood, and moved with her to a caravan at remote Cape Otway, three hours southwest of Melbourne, with a crazy plan to launch a quarterly magazine of Australian fiction.

For the next couple of decades, he and Harwood would run Pascoe Publishing and Australian Short Stories. Helen Garner published her first short fiction in the quarterly, and Tim Winton and Gillian Mears were among the young writers it nurtured. Pascoe kept it going by working as a lighthouse guide, indigenous language researcher and farm fencer (“I’d take my dog to work, which is a lovely thing to do, and I’d have a fire going and boil a billy. Where’s the downside?”). His literary confreres were working-class lefties like Frank Hardy and Barry Dickins, and he voiced a disdain for the “snobs” who ran university literature courses. Hilary McPhee, who published Pascoe’s first novel Fox while at Penguin Books in the ’80s, recalls him fondly as a shaggy-haired yarn-spinner who was “incredibly stubborn, determined and funny”. McPhee cites his stewardship of Australian Short Stories as an extraordinary feat — Pascoe kept the magazine going for 16 years, along the way writing three novels and two short story collections that reflected his own deepening dive into his indigenous ancestry. By the time he was 40, he had fully identified as Koori and was immersing himself in indigenous language and the history of frontier massacres, a subject that sparked ructions in the farming community where he lived.

Even today, the profound impact of this period is palpable when Pascoe talks about the years he spent in libraries and in meetings with indigenous elders such as Zelda Couzens from eastern Victoria, who lambasted his ignorance of Aboriginal history. “They were talking about what happened in the ‘war’, and I had been taught that no war had ever been fought on our soil,” he recalls. “So when my aunty Zelda was talking about the war I’d say ‘What war?’ and she’d say ‘’You infuriate me! You’re interrupting me, and you’re stupid — there was a war!’” Pascoe says he found indigenous ancestors on both sides of his family, tracing them to Tasmania, to the Bunurong people of Victoria and the Yuin of southern NSW.

By the early 2000s, he had moved to Gipsy Point with Harwood and pushed aside fiction to write Convincing Ground, a 302-page polemic about Aboriginal dispossession and its legacies. In one passage he embraced the animist spirituality of traditional Aborigines, claiming to have witnessed quails gathering at the side of the road when Zelda Couzens passed by. In the book and in interviews he admitted that his indigenous ancestry was distant, and he was “more Cornish than Koori”. It was all too much for the conservative commentator Andrew Bolt, who mocked Pascoe on his blog for succumbing to “the romance of the Noble Savage… the thrill of the superstitious”.

Others took legal action over such ridicule; Pascoe preferred to gently mock “Bolty” by offering to explain everything over a beer. The explanation would be long and involved, as Pascoe admits — he once stated that his great-grandmother had an Aboriginal name, but declines to elaborate today because the claim has put him in dispute with the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre, which polices claims of Aboriginality in that state. It’s an example of how contested this territory can be, and Pascoe acknowledges the “schizophrenic” nature of having both Anglo and indigenous ancestry yet choosing one over the other. He has been to Britain and walked around the Cornish landscape of his forebears, he says, but felt nothing. “When people ask me whether I’m ‘really’ Aboriginal, because I’m so pale, I say ‘Yeah’. And when they ask me whether I can explain it, I say: ‘Have you got three hours?’”

In the broader indigenous community, Pascoe’s acceptance is now so established that he is routinely bestowed the honorific “uncle”, and he was anointed Person of the Year at the 2018 Dreamtime Awards — a ceremony he attended in his first suit jacket, bought from a charity shop. Seven years ago he was summoned to a meeting with Uncle Max Dulumunmum Harrison, a Yuin elder, arriving to find himself at a cultural ceremony that lasted a number of days (“fortunately I had a swag in the car”). It was the beginning of his complete acculturation into indigenous lore, although Pascoe again declines to elaborate. “This is an honour but not something we talk about, nor do we point to the marks,” he says, adding that he prefers not to use the term “initiated” because of its capacity to be overdramatised. “I don’t call myself an elder,” he says, “just older.”

It was during the research for Convincing Ground that Pascoe came across colonial-era descriptions of Aborigines living in villages and harvesting crops, activities he had never learnt about during his 1960s university education. Researching the topic, he discovered that other historians were pursuing the same material: in 2008 the eccentric independent scholar Rupert Gerritsen published Australia and the Origins of Agriculture, which argued that Aborigines were agriculturalists as much as hunter-gatherers; three years later ANU historian Bill Gammage released The Biggest Estate On Earth, a major study of how Aborigines used fire, dams and cropping to shape the landscape and farm it sustainably.

In Dark Emu, Pascoe acknowledges his debt to both authors; like them, he draws on the eyewitness accounts of colonial settlers and explorers to describe unfamiliar scenes of Aborigines living in permanent villages, building stone dwellings and devising elaborate fish traps, irrigation systems and cultivation methods for vegetables and grains. Gerritsen died in 2013 without ever achieving a university job, and Pascoe cites him as a scholar who languished in obscurity because his theories contradicted the mainstream view. “Rupert should have got all the credit for Dark Emu,” he says candidly, a sentiment that gets ready agreement from Gerritsen’s brother Rolf, a professor of economic and indigenous policy studies at Charles Darwin University. “Ninety per cent of Bruce’s book is taken from my brother’s research,” Rolf Gerritsen says with a chuckle, adding that this is not to belittle Pascoe’s considerable achievement in popularising complex issues and shifting the national conversation about indigenous history.

Pascoe sent the manuscript of Dark Emu to Broome-based Magabala Books, the independent press that had published his young-adult fiction. The company’s publisher, Rachel Bin Salleh, laughs sheepishly when she recalls that their initial print run was 800 copies. “We had no idea how it was going to be received,” she says. “We really underestimated the thirst for knowledge of this subject matter.” The book’s brevity is a key to its appeal; Magabala wisely reined it in to 175 pages with footnotes and bibliography, making it popular among teachers. Pascoe also married its historical themes to contemporary issues such as land management and climate change; its final pages are a veritable call to arms for younger readers.

Many academic historians admire Pascoe’s achievement, among them Professor Lynette Russell of Monash University, the co-author of a new book of revisionist indigenous history, Australia’s First Naturalists. “What Bruce has done is trawl the records and found fantastically rich and useful material,” Russell says. “I’m a big fan of the book because it’s had such a huge impact.” Bill Gammage likewise praises Pascoe’s gift for shaping a story that challenges the reader’s preconceptions. He cites Dark Emu’s account of the 1844 encounter between explorer Charles Sturt and several hundred Aborigines living in an established village in outback Queensland: Sturt’s journal describes a welcoming party that offered him water, roast duck, cake and a hut to sleep in, prompting Pascoe to dryly remark: “Sturt was doing it tough among the savages, all right.”

It’s when Pascoe wades into more polemical terrain that he incurs a rebuke from academics. Throughout Dark Emu, he argues that historical accounts of Aboriginal housing, farming and fishing were suppressed for most of the past 150 years. The myth that Aborigines were simple nomads was perpetuated to justify white occupation, he asserts, and scholars who tried to argue otherwise were marginalised so effectively that it is rare to come across a text after 1880 that describes Aboriginal fishing systems or intensive grain and vegetable harvesting.

That claim is “ridiculous”, says Professor Peter Hiscock, chair of archaeology at Sydney University, who cites numerous studies of indigenous fish-farming and plant-cultivation. “The literature on this subject is massive,” says Hiscock, “so the assertion that it is ignored or hidden does not reflect the reality of the disciplines; it must reflect the political mindset of Pascoe.” Ian McNiven of Monash University likewise says Pascoe’s assertion flies in the face of decades of published research, as does the veteran archaeologist Harry Lourandos, who began documenting traditional indigenous eel farms in the 1970s.

Many academic experts also believe Dark Emu romanticises pre-contact indigenous society as an Eden of harmony and pacifism, when in fact it was often a brutally tough survivalist way of life. It’s a criticism most are reluctant to air publicly, given the sensitivity of contradicting a popular indigenous historian, although even Gammage chuckles at some of Pascoe’s loftier claims about stone age Aborigines inventing democracy and baking. “I wouldn’t push these things too far,” Gammage says. “We don’t know what was going on in the world 65,000 years ago.”

For archaeologists such as Ian McNiven and Harry Lourandos, however, any criticism of Pascoe is tempered by their delight at seeing a book detailing the complexities of indigenous culture riding high in the bestseller lists. Lourandos — now an adjunct professor at James Cook University — agrees with Pascoe that much of Dark Emu’s content is little known to the broader reading public, and he’s heartened to see an indigenous author filling that gap. “He’s appealing to that younger generation and he’s got the persona of a guru, and once you get that, you are celestialised,” Lourandos notes wryly. “In this age of political unrest, there’s a hankering for that.”

Pascoe dedicates Dark Emu to “the Australians”, an all-inclusive phrase that encapsulates the book’s ultimately hopeful tone. His friend and fellow writer Gregory Day theorises that Pascoe connects with general readers because “he knows what it feels like to be a whitefella — in a sense, Bruce is translating it for whitefellas”. The book’s final pages are an impassioned treatise that argues Australia could heal from its racial scars and secure its ecological future by adopting indigenous systems of governance and landcare. Get rid of wheat and grow native grass; eat kangaroo instead of cow; replace capitalism with “Aboriginalism”. It’s a gospel Pascoe now preaches passionately in his public appearances, detailing his own efforts to cultivate kangaroo grass and daisy yams on the small farming block in Mallacoota.

The personal cost of that mission has been high, for he and Harwood separated in 2017 after 35 years together, a split Pascoe attributes to his many absences and his late-life mission to pursue farming. “I think Lyn didn’t want to take on another venture as demanding as that,” he says. “She’s probably right, but I couldn’t not do this job.” Harwood still lives nearby, at Gipsy Point, and Pascoe describes her as “my best friend”, his voice cracking.

Their son Jack, who is 34 and works in land management in Cape Otway, acknowledges the scale of the task his father has taken on. “He’s a 72-year-old man who’s literally just bought a farm and he’s travelling around the country to speak at every opportunity,” Jack says. “Of course we’re concerned, but would you try to stop someone who is that passionate? No, what’s the point?”

Pascoe has a big year ahead of him: two new versions of Dark Emu are being released, one for primary school children and another a high school geography text. There’s also a new collection of his stories, two young adult books and a novel, Imperial Harvest, which he describes ominously as a butchering of world history incorporating “love and sex while rolling around on bear skins”. He’s also launching Black Duck Foods, a company seeking to commercialise his indigenous produce business. Some years ago he made the rash decision to bake a loaf of bread from native flour on breakfast television, a culinary disaster from which he learnt a valuable lesson. These days he teams up with top chefs such as Ben Shewry and David Moyle, who in April accompanied him to the Chairman’s Lunch at the Melbourne Food & Wine Festival to bake a “sensational” loaf of bread.

“It’s a bit late for me to be making a million dollars but I’m not particularly interested,” he says. “I live a terrific life and I don’t need much. But I need time and I can see how depressed our communities are. I’m really in a panic of getting things done.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout