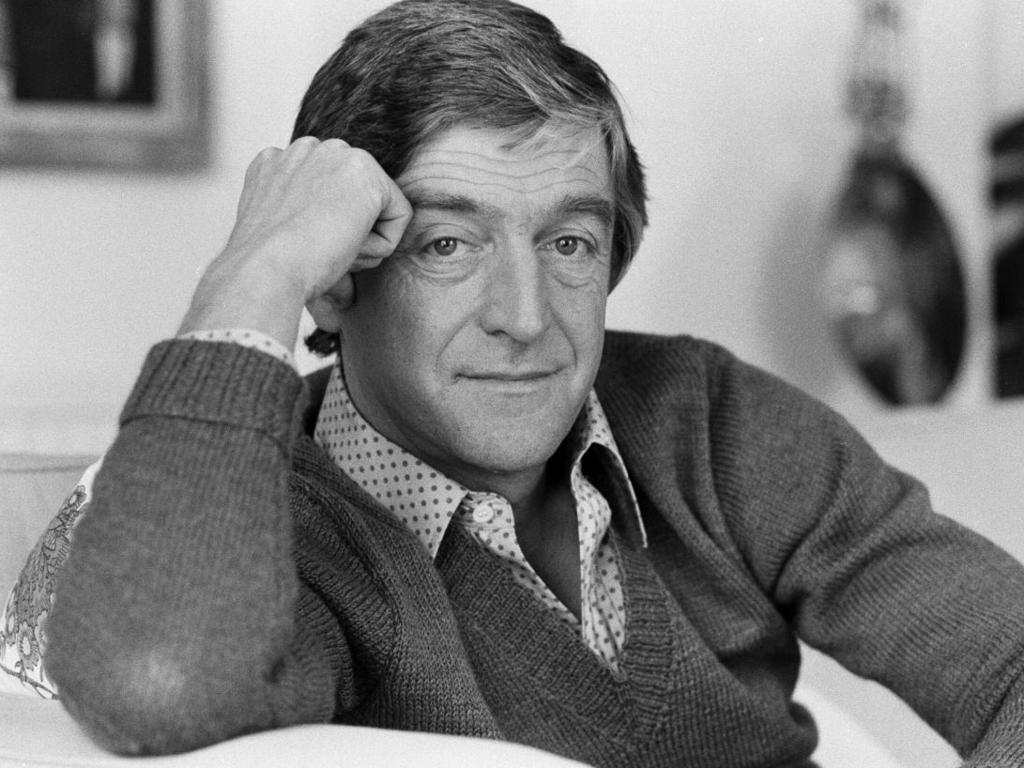

Michael Parkinson won over the biggest names by never frightening them

The most difficult interview of Michael Parkinson’s long career in journalism was with a wordless Australian in the mid-70s.

The most difficult interview of Michael Parkinson’s long career in journalism was with a wordless Australian in the mid-70s.

This Australian was an emu hand puppet animated by former Australian television producer Rod Hull, simply called Emu.

Emu sized up Parkinson, tore up his interview notes, bit his upper thigh and eventually bowled him out of the famous swivel chair while attacking his signature bouffant.

It was 1976, in London. Parkinson was already well known, and had interviewed the likes of John Lennon and Yoko Ono, but the Emu encounter was a landmark.

Parkinson, who died last week, said later: “I will always be remembered for that bloody bird!”

But Parkinson became unstoppable and many of us remember his Australian years when he imported his chat show to Sydney for a series of shows, first on the ABC and later Channels 9 and 10, starting in 1979.

There was never anything adventurous about Parkinson’s interviewing – the reason he was able to attract so many “ungettable” big names was precisely because he would not upset them.

In Australia, Parkinson served up a mostly predictable menu of famous Australians: Bob Hawke, Shane Warne, Paul Hogan and AFL legend Ron Barassi. None was ever threatened by the prospect of Parkinson on live television. He would never be a David Frost or an Andrew Denton, whose approaches, so deeply researched, meant that a curve ball could be expected just after the happy families small talk.

Parkinson can be criticised for that. But it was also his towering strength. He enticed Hawke to acknowledge his playboy past, and he had Warne admit how lost he was having retired.

But it was perhaps his unlikely interview with media boss Kerry Packer that exhibited the best Parkinson could extract from his always relaxed, off-guard guests.

Packer was commonly loath to talk about his own life. But he told Parkinson of his privileged boyhood with terrific humour and how it had shaped not just him, but how Packer treated his own equally advantaged children.

If Parkinson believed Packer had ruined his beloved traditional cricket – and he said that many believed that to be the case – he never let on.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout