One of the toughest, if not the toughest, political piece to write during an election campaign is the newspaper’s editorial, which declares which party has the support of the masthead and is thus “endorsed” on polling eve.

Sometimes, the choice is so difficult that newspapers don’t make an endorsement of either side.

When The Washington Post decided not to publish a presidential endorsement editorial in 2024 in the lead-up to the contest between Donald Trump and Kamala Harris – perhaps understandably, given the choice – it created a public furore, prompted accusations of weakness and divided editorial staff.

The Post had previously endorsed both Republican and Democratic candidates so its decision to sit on the fence was seen as a way to avoid offending Trump if it didn’t endorse him, or causing a staff revolt if it did.

But would an editorial endorsement from The Post have changed a single vote?

It may have changed people’s attitudes to the newspaper but, in my view, the controversy embodied the internal angst, the management power struggles, the academic discussions and political leaders’ expectations that are entirely out of tune with what an election editorial is and what impact it has on voters.

When newspapers were the main source of news, information and opinion, there was no doubt readers more closely followed the editorial line; indeed people tended to stay loyal to a particular masthead because of its editorial line. (My grandfather only ever bought The Sun.)

Now the editorial endorsement of a leader is more closely followed by political leaders than anyone else.

The editorial tends to be a statement of principles, reflect the philosophy and policy of the newspaper, and is in line with the proprietor’s general views. It shows a consistency with the editorial assessment and treatment of the government and opposition over the previous three years.

Editorials, now, do not dictate how people should vote.

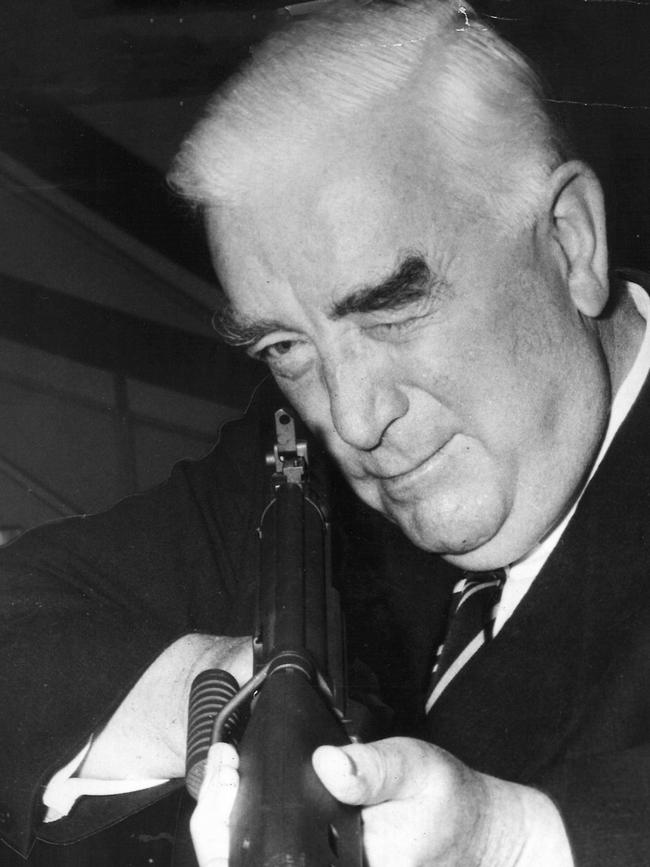

In the 1960s, changes in editorial support at the Fairfax-owned The Sydney Morning Herald, first away from Robert Menzies and the Coalition in 1961 to Arthur Calwell and Labor, and then back to Menzies in 1963, caused huge ructions within the Fairfax family, management and senior editorial staff.

The editorials, written by Warwick Fairfax, turned against Menzies because of the credit squeeze and failures on defence policy in relation to Indonesia after Fairfax developed a personal relationship with Calwell, and then shifted back to the sitting PM because of subsequent dissatisfaction with the ALP on defence and foreign policy.

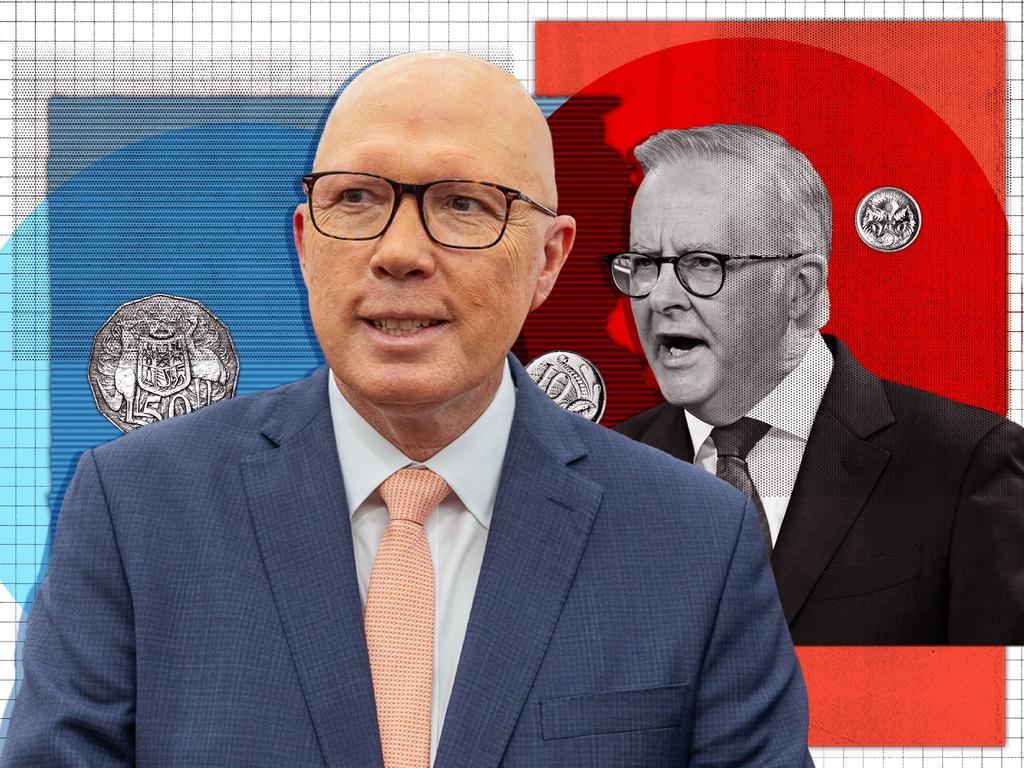

After the 2025 federal election there is a new narrative that, as the readership and influence of legacy media are challenged by social media, the decline of the influence of editorial endorsement is evidence “major media companies have been left to bellow from the sidelines”.

A research paper released by The Australia Institute last week, titled “Yesterday’s kingmakers, today’s spectators”, argues that “securing newspaper endorsements was once a key part of running a successful Australian election campaign, through which Australian media shaped Australian politics”.

“The result of the 2025 federal election was proof that the influence of major media companies over voter opinion has declined,” the paper said after analysing editorial endorsements from major newspapers and election results.

The institute found: “In the two most recent federal elections, the winning party was endorsed by fewer than half of all major newspapers, and from 1996 to 2019, the winner of every federal election was endorsed by the majority of newspapers. In 2022 and 2025, most newspapers supported the loser.”

With a somewhat romantic, out-of-date and overstated declaration, the paper claims that “although the spectre of media moguls as political kingmakers still looms large in the imagination of Australia’s political class, the opinions and endorsements published by Australia’s major media outlets now have little influence over how Australians actually vote”.

The study draws on various reports and papers looking at the moguls and “large oligopolies that carved up Australia’s media” in a pervasive attack on progressive politics as recent years demonstrate the failure of the newspapers to exercise influence. But the academic reasoning, the historical examples and the selected data designed to show the recent federal election results and aggregated newspaper editorial endorsements fail a test of political reality and logic.

What’s more, the narrative seems to be that the majority of newspaper editorials have favoured the Coalition over “progressive” Labor.

“In 2022, despite receiving a minority of major newspaper endorsements, Labor broke past the media gatekeepers, winning government with a large two-party-preferred swing in their favour,” the report said.

The argument is that in the 2022 and 2025 elections, “legacy newspaper and TV media has been left to bellow from the sidelines” because “newspaper endorsements and televised debates now appear to have little to no influence on public opinion”.

“Australian newspaper endorsements have overwhelmingly favoured the Coalition over Labor in the past three decades, with 2007 and 2010 being the only exceptions,” the report said.

As evidence of historical influence, the report refers to The SMH/Menzies editorials of 1961 and 1963, saying that Menzies “almost lost” in 1961 when the SMH editorialised against him, and yet the Coalition won in 1963 as well – suggesting the SMH editorial’s influence was limited, even back then. What’s more, the report argues that Anthony Albanese’s Labor government is the first in a generation to be elected when there was a majority of newspapers editorialising against it, and to make its point it tabulates the editorials and election results since 1996.

Of course, leaving out the 1993 election which Paul Keating won with only one newspaper – The Daily Telegraph – endorsing him suggests the paper’s findings have been carefully cherrypicked. The truth is that in 1993, it was not editorial endorsements that counted but a value added tax from John Hewson. Likewise, in 1998 – the GST election – almost 80 per cent of editorials endorsed the re-election of John Howard’s government. History shows that Howard’s tax reforms and proposed introduction of GST prompted a huge voter backlash that cost the Coalition 20 seats. In short, both in 1993 and 1998, overwhelming editorial opinions were ignored by voters.

“Between 1996 and 2019, only two elections saw half or more of the major newspapers endorsing the ALP, and in both cases they formed government. In 2007, 60 per cent of major newspapers backed the election of the ALP after its 11 years in opposition,” the Australia Institute report said.

After his election, which was endorsed by The Australian, Kevin Rudd became the most popular prime minister in the history of Newspoll which suggests there was more at play in the 2007 election – such as a tired Coalition government – than a ringing endorsement from this masthead.

As much as it pains me to say, the blood, sweat and anguish that goes into the big election editorial has never counted for much with voters. To suggest there’s been a sudden decline of their influence ignores the political reality.

Dennis Shanahan is the national editor of The Australian