‘Engage with Taliban before Afghanistan becomes another North Korea’: plea from Australian media mogul bringing education to Afghan girls

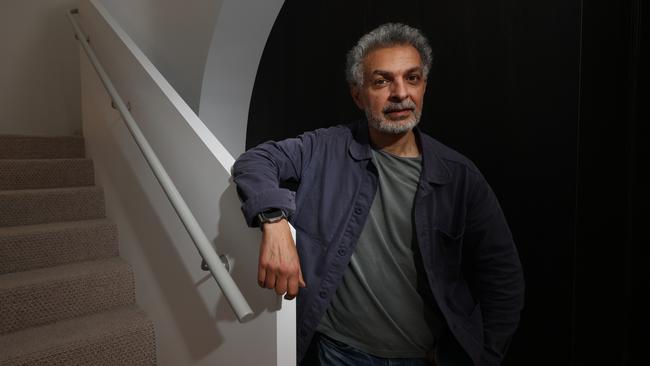

Australian media mogul Saad Mohseni plays a cat-and-mouse game with the Taliban, airing TV to millions of Afghan girls, but says we have to engage with our former enemy before it’s too late.

The Australian media mogul who founded Afghanistan’s first television network is quietly playing a key role in pushing the incoming Trump administration to engage with the Taliban, in what he believes is the last chance for Afghan women to regain a measure of freedom in Afghanistan and for girls to receive an education.

Since the fall of Kabul in August 2021, Moby Group chief executive Saad Mohseni has been engaged in cat-and-mouse game with the Taliban, keeping his Tolo TV network on air – with female news presenters in front of the cameras – in the face of a relentless clampdown by the fundamentalist regime. Mohseni’s message is simple: “We have a window of opportunity with some of the more pragmatic elements within the Taliban who want to talk to the Americans,” he tells The Australian during a brief visit to Melbourne to see family. “But if the world disengages, Afghanistan becomes another North Korea.”

The 58-year-old powerbroker, now based in London and Dubai, has not returned to Afghanistan since the Taliban regained control, concerned the regime may use his presence to legitimise their rule. But he has travelled constantly, throughout the region and Europe, and often to Washington, trying to keep Afghanistan on the world’s radar.

Mohseni also speaks regularly to his Taliban contacts – high-ranking officials in Kabul, Dubai, Doha and Abu Dhabi – many of whom consider themselves pragmatists and are far more media-savvy than the Kandahar-based extremists.

That puts the former Melbourne banker in a unique position. He is a long-time friend of both President Joe Biden’s US National Security Adviser, Jake Sullivan, with whom he served on the board of the International Crisis Group, and Donald Trump’s pick for the post in his new administration, Mike Waltz, who fought the Taliban in multiple combat tours of Afghanistan.

Waltz, now a Florida congressman, has been highly critical of moves to establish links with his former foe.

Mohseni is coy about his discussions with all sides, but fears that under Trump, the US may cut humanitarian assistance to Afghanistan and increase already crippling sanctions on the country. And he’s painfully aware the world’s focus has shifted to other priorities: Ukraine, Gaza, China.

The Biden administration was humiliated by the chaotic withdrawal of US troops as the Taliban swept virtually unopposed into Kabul, albeit under a deal first ordered by Trump.

Neither side of politics has much appetite to re-engage with the Taliban, except to punish the regime for its appalling treatment of women and girls.

That’s understandable, says Mohseni, but a grave mistake. “Engaging doesn’t mean recognition; it means just talking to them. Disengaging means just forgetting about the country and, in the process, you punish the people. I have yet to meet one Taliban member who has lost weight – they’re looking pretty healthy to me, and they’re not going to suffer because of this.

“If the moderates in the Taliban see a path to the world re-engaging, there’s going to be more reason for them to challenge their own leadership, but they’re not going to take massive risk if there’s no light at the end of the tunnel.”

It’s a position Mohseni advocates forcefully in a new book, Radio Free Afghanistan: A 20-year odyssey for an independent voice in Kabul.

It’s also a message that comes at some personal cost: he’s accused, even by some high-placed friends in the US and Europe, of cosying up to the enemy.

But Mohseni has more reason than most to loathe the Taliban, who killed 12 members of his staff, seven of them in a targeted suicide bomb attack on a Tolo bus.

He recalls a meeting with one senior European official who told him angrily: “I’m not going to engage with the Taliban. Never. We cannot engage with the Taliban because of what they’re doing to girls and women.” Mohseni says the attitude was one he heard constantly: “A reaction to terrible cruelty that was unwittingly cruel itself.”

The irony is that his television network is single-handedly providing the only education many Afghan girls can now access – airing more than 800 hours of education programming every year.

It’s a delicate – and dangerous – tightrope, with Tolo broadcasting educational programs on mathematics, physics, chemistry and biology for children in years 7, 8 and 9, in both Dari and Pashto, the two main languages in Afghanistan. Professional teachers – many of them women who lost their jobs when the Taliban regained power – host the shows.

A recent baseline survey showed that kids who hadn’t done the TV courses for mathematics scored 25 per cent; those who watched the programs scored 55 per cent; others who watched and were also tutored via WhatsApp scored 75 per cent.

“So you can triple their scores with a little bit of coaching and these television programs,” Mohseni says. “For girls who cannot go to school, it’s transformative. It gives them an option for the future. It’s not an alternative to school but it buys them time. It’s a Band-Aid solution but it’s a very effective one. This programming on our different platforms, it buys people hope for the future when hopefully schools reopen.”

Tolo’s news programs have run more than a thousand stories about girls’ education, even finding clerics who will condemn the ban along religious lines.

Mohseni says there is a “disconnect between edict and implementation” of Taliban policies.

“If you go to the airport, a woman is going to stamp your passport. Women are still driving, and they’re walking around the city, faces uncovered in the major cities. So the situation on the ground is a lot more nuanced.”

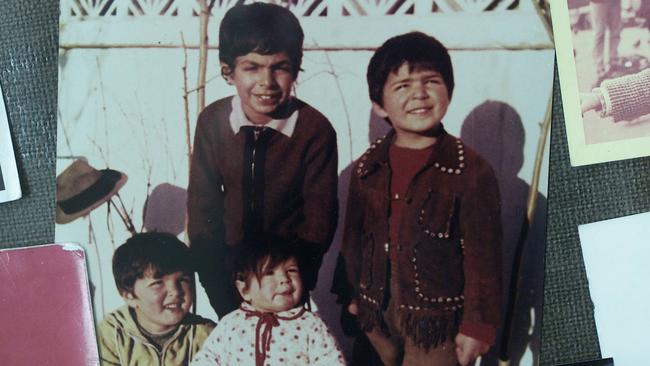

Mohseni grew up in Australia, the son of an Afghan diplomat who had been stationed in Tokyo and sought asylum here in 1982 because of the Soviet invasion.

When the fundamentalists were forced out in 2001, Mohseni saw an opportunity and moved back to his homeland, launching Afghanistan’s first private radio station and TV station, airing news programs, game shows, soap operas, cop dramas and a cheesy talent show, Afghan Star, which had 12 million people tuning in every night.

The music and soap operas that were once the staple of the network have long gone.

“The Taliban are the enemies of fun,” Mohseni says. “But pretty much everything else is on. We’ve got game shows, we’ve got cooking shows, travel shows and news. And our women reporters may have to wear a surgical mask to comply with the Taliban edict of covering their faces, but they’re in front of the camera and behind the camera.”

With only a handful of foreign correspondents now reporting from Afghanistan, much of the news out of the country comes from Tolo journalists who continue to file reports – sometimes critical of the regime – from every province.

Mohseni’s challenge in Washington is to convince those who have the ear of a wildly unpredictable new president that it is in America’s interests to talk to moderate elements of the Taliban.

He points out that with the regime now in a brutal power struggle with former allies – reborn elements of terrorist groups al-Qaeda and Islamic State – the US and the Taliban have common enemies.

“There are risks in Afghanistan for the Trump administration and that’s why it’s important for them to understand that there is an opportunity to keep the hard-won gains of the past two decades,” Mohseni says.

“Of course, you can’t demand these things; you just ask that they not forget.”

Radio Free Afghanistan: A 20-year odyssey for an independent voice in Kabul, by Saad Mohseni with Jenna Krajeski, published by William Collins

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout