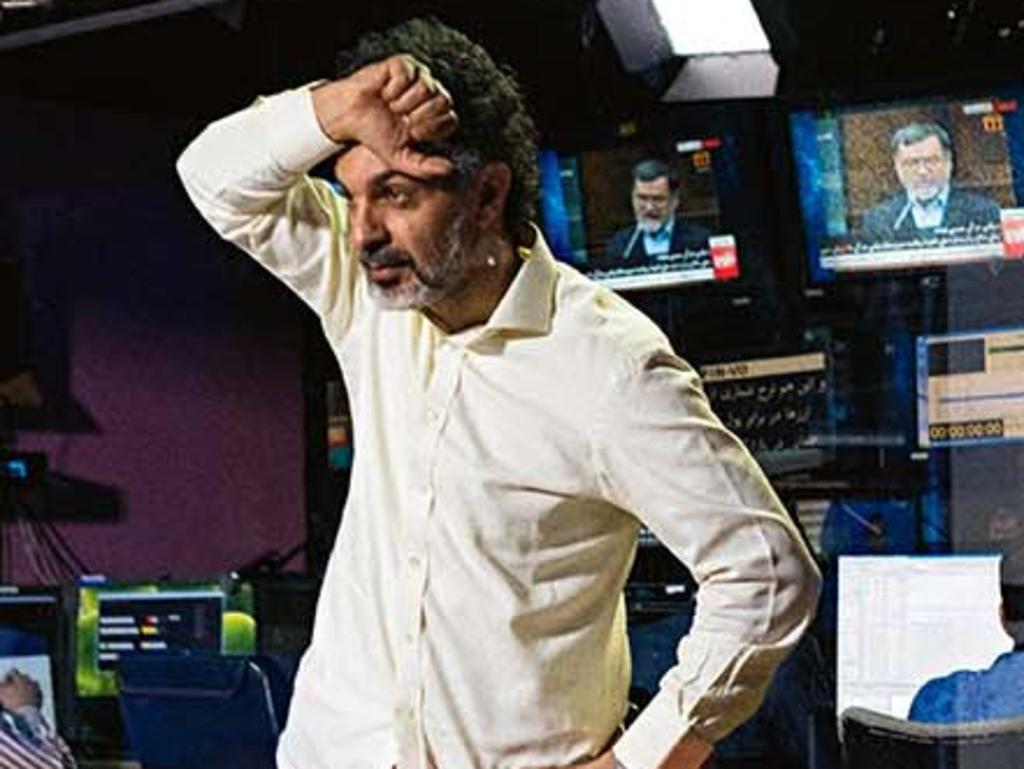

Australian media mogul Saad Mohseni takes on Taliban

The Australian entrepreneur who founded Afghanistan’s first television network has begun enacting contingency plans to keep broadcasting in the event Kabul falls to the Taliban.

The Australian entrepreneur who founded Afghanistan’s first television network has begun enacting contingency plans to keep broadcasting and to protect his 300 journalists in the event Kabul falls to the Taliban.

MOBY Group CEO Saad Mohseni told The Australian: “We will persist, we will hang in there for as long as we can, but the future is far from certain.”

The security environment in Kabul is rapidly deteriorating, with rocket attacks launched against the city on Tuesday, hours after ceasefire talks between the Taliban and the Afghan government broke down.

Mr Mohseni’s TOLO television network employs 400 people, many of them prominent journalists who have been designated by the Taliban as military targets “due to their disrespectful and hostile actions towards the Afghan Mujahid nation”.

The Melbourne-raised Mr Mohseni describes the prospect of a Taliban takeover as “an existential threat, not just to our organisation, but to our people”.

“We’re very mindful of our staff members, their lives, the security situation, their families, and we will do what we can to ensure they remain safe,” he said.

The Taliban has ramped up the targeted assassination of journalists in the past year, but TOLO TV has long been in the Taliban’s sights. Twelve of its reporters have been killed in the past five years.

“We know the pain of losing journalists,” Mr Mohseni said.

Many TOLO staff move between different houses to sleep each night, trying to avoid a predictable pattern.

“It keeps the terrorists on their toes,” Mr Mohseni said.

But in recent days the Taliban has swept through the north of the country, capturing towns without a fight. Mr Mohseni is bitterly disappointed by the way the US and its allies – Australia included – have fled.

“It just didn’t give our security forces enough time; it was pretty much cut and run,” he said.

“I mean there has to be some responsibility. Look at the Afghan women and girls who went to school, were promised something by the international community. They were told that ‘we would have your back’, these aspirational young people who’ve come with the promise that the world is going to stick by them.”

In Kabul, some of the few remaining diplomats report a foreboding last-days-of-Saigon feel; a final chapter that might yet result in helicopters lifting off from the roof of the US Embassy.

Already the Taliban is beheading government officials in captured towns and whipping women for going out without male chaperones.

“They’re doing exactly what they did in the 1990s, so this whole narrative that the Taliban have changed, it’s complete bullshit,” Mr Mohseni said. “They will never abandon their ideology because that’s what defines who they are.”

Mr Mohseni is not willing to bet on how long the government of President Ashraf Ghani might last.

“You know, they could survive,” he said. “My suspicion is, they’re going to struggle.”

The Taliban, he points out, have been taking all the major entry points into Afghanistan, most recently Spin Boldak, the crucial crossing between Kandahar in southern Afghanistan and Baluchistan in Pakistan.

“The intention is to choke off the central government in terms of revenue – customs is the primary source of income. I think their idea is to choke off the city and force the government into surrendering.”

The fundamentalist Taliban are unlikely to allow anything like Mr Mohseni’s independent television, radio and online media to survive.

“The Taliban are the sort of people who say – to quote Henry Ford – you can have any colour you want, as long as it’s black. There’s no way they’re going to accept a news network that’s telling the truth. As far as our entertainment programs are concerned, the Taliban have shown time and time again, they’re the enemies of fun. They don’t want music, they don’t want entertainment, they don’t want banter, they don’t want anything that brings a smile to people’s faces.”

Mr Mohseni grew up in Australia, the son of an Afghan diplomat who sought asylum in Australia when the Taliban came to power.

When the fundamentalists were forced out in 2001, Mr Mohseni saw an opportunity and moved back to his homeland, launching Afghanistan’s first private radio station. His MOBY Group is now the country’s largest media company, owning TOLO TV and dozens of other assets.

The security challenges in Kabul in the coming weeks won’t just be the Taliban, he says: anarchy is an even bigger threat.

“If the system collapses, what I fear more than anything is criminal organisations, looters, people trying to enter the office building. There will be more attacks on people, sexual abuse, car-jackings.”

Asked what the country will look like in a year, he offers a prediction he admits “may be more wishful thinking” – in which the Taliban take over by stealth rather than violence, putting on their best face to attract international aid and assistance. “It’s an Afghanistan that may not be as progressive at it is today, but where the Taliban are more tolerant of women’s rights, of girls’ education and a free press. That’s my wish.”

What does he think are the odds of that happening?

“Twenty per cent,” he says. “But I’m an optimist.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout