60 Minutes in Beirut: in ratings war, ethics and risks are first casualties

What’s the promo? That’s the question that becomes routine when you’re working in commercial current affairs TV.

What’s the promo? That’s the question that becomes routine when you’re working in commercial current affairs television.

And it’s most likely a question that was asked before the 60 Minutes team embarked on their ill-fated trip to Beirut where four of their team face possible kidnapping charges.

While it’s clear large sections of the public cannot understand how 60 Minutes has found itself in this mess, the culture that exists in prime-time commercial television may explain it.

A similar culture exists at the Seven Network — and they certainly should not be taking any joy in the discomfort of their Nine colleagues as it could, quite easily, have been one of their teams caught in Beirut.

Firstly, in commercial current affairs television ratings rule.

Without good ratings you don’t get good advertising revenues and without good revenues you don’t have a show or a business.

I lived around this atmosphere for seven years when I worked at Nine in Sydney — first as a reporter on the Sunday program and then as its executive producer.

Every morning without fail, at 9.05, the ratings for the previous night drop into your email box. For the next five minutes, executive producers are engrossed in examining which parts of their programs worked and which did not.

And whose program at Nine did well and whose bombed, and how Seven, the main competitor, did.

The 9.05 email is a daily, public judgment of your work and a strong indicator of whether in the medium term you will have a job or not.

Had the Beirut operation gone smoothly, Nine probably would have had one of the highest-rating programs of the year.

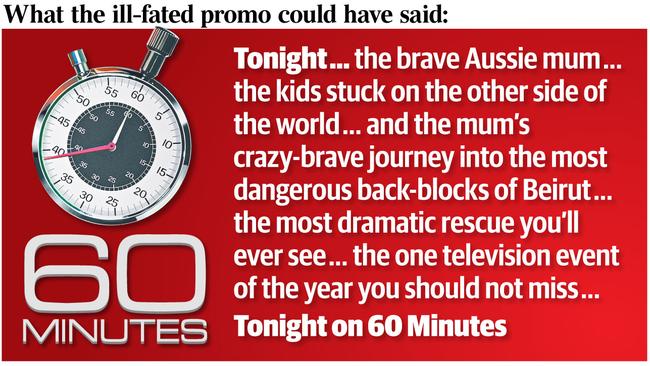

The promo would have been something like this: “Tonight (tick, tick, tick) … the brave Aussie mum … the kids stuck on the other side of the world … and the mum’s crazy-brave journey into the most dangerous back-blocks of Beirut … the most dramatic rescue you’ll ever see … (then, with a slower, deeper voice) … the one television event of the year you should not miss … Tonight on 60 Minutes (tick, tick, tick.)”

And over these words you would have heard ominous music and seen the dramatic pictures of the children being snatched.

The program probably would have added an extra 200,000 or so viewers to its average audience — reporter Tara Brown and producer Stephen Rice would have been heroes around the Nine compound, even if just for one day. Nine’s sales people would have been pumped up and, most importantly, Seven would have been devastated.

That’s how it was meant to go.

60 Minutes is a producer-driven show — its “stars”, such as Brown, are often doing interviews for three or four different stories at once, all co-ordinated by the producers.

Producers often even write some of the questions — while reporters rush from one story to another, producers tend to stay attached to the one story.

Often the producer has several meetings with the main interview subject and does a pre-interview with them even before the reporter meets the person.

It’s not unusual that the first time a reporter meets the main “talent” is when the lights are set up and they walk in to do the interview. The producer is the one whose job it is to get that person “over the line” — that is, convince them to do the interview.

Often in commercial current affairs the producer will know more about the story than the reporter does.

The producer takes charge: arranging travel, which pictures are needed, delivering talent to be interviewed, overseeing the editing and finding the “promo grab”.

A key factor in how well a story rates is “the promo” — the 20-second ad that tries to hook people into watching the program.

In the Channel Nine bar, where we would gather most Friday nights, then chief executive David Leckie would often make clear to executive producers what he thought of their promos from that week.

Putting diplomatic niceties to the side, Leckie could rate them anywhere from “f. king awful” or “shithouse” to “brilliant.”

For 60 Minutes, the most important promo is the one that runs in the Sunday night news — the highest-rating bulletin of the week and shortly before 60 Minutes goes to air.

While the Sunday program was not under the same pressure for ratings as it was not prime time, those of us at Sunday were aware of the pressures facing our colleagues in the cottages that make up Nine’s Sydney headquarters.

In terms of the Beirut debacle, Nine is now fighting on several fronts.

Its first priority is to get its four employees home — the move to quickly dispatch news director Darren Wick was a good one.

Wick is an experienced news man who has been speaking to a wide range of people in Australia and Lebanon.

He’s calm under pressure and it’s clear he has quickly grasped that, for the moment, he must be a diplomat — for the sake of his four staff he must publicly show respect for the Lebanese government, legal system and those who work within it.

My experience in Lebanon is that as welcoming as Lebanese officials will be to an Australian they will also be looking for any signs of arrogance — by all accounts Wick has struck the right tone with all those he is meeting.

Secondly, Nine is fighting a public relations battle in Australia. It’s clearly losing this — Nine’s brand is being damaged and 60 Minutes’ brand is being smashed — but in these unique circumstances it really has no choice.

To go on the front foot in Australia right now could jeopardise its four employees in Beirut. Getting the four staff home quickly and safely must be Nine’s single priority at the moment.

Third, Nine is trying to manage the families of the 60 Minutes team — this, too, is hugely difficult, as shown yesterday by the families saying they were “worried sick.”

Finally, Nine must seriously examine its current affairs culture.

A full and authentic investigation is best done when its staff are back home, but it should not simply be forgotten when the 60 Minutes team returns.

If those doing chequebook journalism — particularly Nine and Seven — do not undertake a serious self-assessment, there’s every possibility this sort of thing will happen again. The sort of culture that has led to this madness in Beirut has been building for years.

From now on, managers at Nine must ask more than just “What’s the promo?”

They must also ask: “What are the risks in doing this story?” and “What are the ethics?”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout