Murderers should take ‘truth serum’ to reveal victims’ bodies, say leading barristers

Two of Australia’s leading criminal defence barristers back the use of sodium pentothal to force convicted murderers to provide details on where they stashed their victims’ bodies.

Two of Australia’s leading criminal defence barristers have backed the use of a chemical truth serum to force convicted murderers to provide details on where they stashed their victims’ bodies.

Former NSW crown prosecutor Margaret Cunneen SC and Victorian barrister Sharon Kermath say governments should at least trial the serum on criminals who have refused to give families peace.

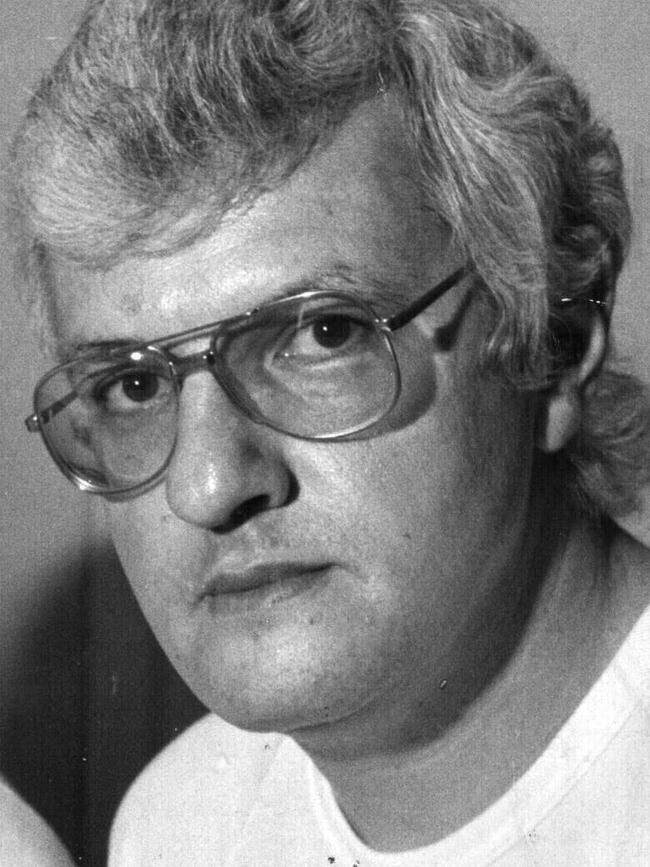

Ms Cunneen’s comments were spurred by the decades-long silence of murderer Bevan Spencer von Einem, who is in jail for life in Adelaide. He was convicted on just one of the so-called Family murders in 1983 but is understood to know much more than he has divulged.

Five boys and young men were killed in that murder spree from 1979, all dying of blood loss from identical injuries.

All the bodies were washed and redressed in the clothes they wore when they were kidnapped.

Von Einem has also been linked to the missing Beaumont children and two girls who went missing from Adelaide Oval in 1973.

But other established members of the legal profession have deemed using Sodium Pentothal as “torture”, saying it strips criminals of fundamental rights and freedoms and undermines the Australian justice system.

The drug, which is used by law enforcement in some Indian states but in no other democracies, slows neural connections, lowers inhibitions and reduce one’s capacity to lie.

Ms Cunneen, who now acts as a defence barrister, told The Australian use of the chemical to learn key details about convicted criminals’ offences was “a great idea”.

“I think it might find some favour now … for the good of the victims,” she said.

Ms Cunneen emphasised the importance of the chemicals to not be used for “self-incrimination” and said protections should be put in place to ensure it was only used following a conviction.

“There could be this protection which covers (the offender) which means it can’t be used to punish them, but it can be used to find information about others or about locations of bodies and so forth,” she said.

“If it was my daughter’s body missing forever I’d want it, too. I suppose the fundamental resistance to it comes from people being forced to give evidence against themselves. In a sense, that’s what it is. It goes against the right not to incriminate oneself.”

Ultimately she suggested government consider a chemical truth-seeking solution, saying: “I think there should be a campaign for it.”

Ms Cunneen’s comments come a year after NSW introduced “no body, no parole” laws following the long-running Chris Dawson trial, preventing murderers from being released on parole unless they reveal the location of their victim’s body.

As things stand, Mr Dawson, 75, will seemingly take to his grave the whereabouts of the body of his wife Lynette, whose murder was told in The Australian’s The Teacher’s Pet podcast. He was sentenced to 24 years’ imprisonment last June.

Ms Kermath, who has acted in criminal matters in Victoria for more than 20 years, said the chemical could provide great closure for victims’ families, but should only be used following extensive trials.

“If it is after a case has finished, and the person has been convicted of murder, and there is a body somewhere, it could be used to give the family closure,” Ms Kermath said.

Ms Kermath raised the issue of consent, saying: “In order to make this happen, the parliament would have to pass a law saying it could be used with consent, and then if consent is not given then reasonable force could be used.”

Veteran criminal defence lawyer Paul Blake disagreed with the notion, comparing use of the chemical to “torture” and saying it would undermine Australia’s judicial system.

“Physically forcing the truth from someone is what is known as torture, which was once also judicially administered,” he said.

“We don’t force anyone to espouse any particular information ever, and this would be breaking down a key pillar of our justice system.”

He continued: “Everyone laughs at the slippery slope argument but we shouldn’t here. Protections that exist will be taken away.”

University of South Australia law professor Rick Sarre said the suggestion the chemical could be used was “complete hocus pocus”.

“It’s a bit like torture,” he said. “We used to use torture to get confessions or get people to tell you things and it was totally unreliable. It sounds as reliable as a polygraph and torture eliciting truth.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout