The Family murders still haunt Adelaide – and one man knows the truth

Bevan Spencer von Einem knows many of Adelaide’s ghastly secrets, possibly going back to the Beaumonts, but he’s not talking.

It was 1979 that broke Adelaide’s heart. That year, the city’s dark carnival of grotesque murders reached a heart-souring climax. Murders of its past were revealed while murders of its future began afresh.

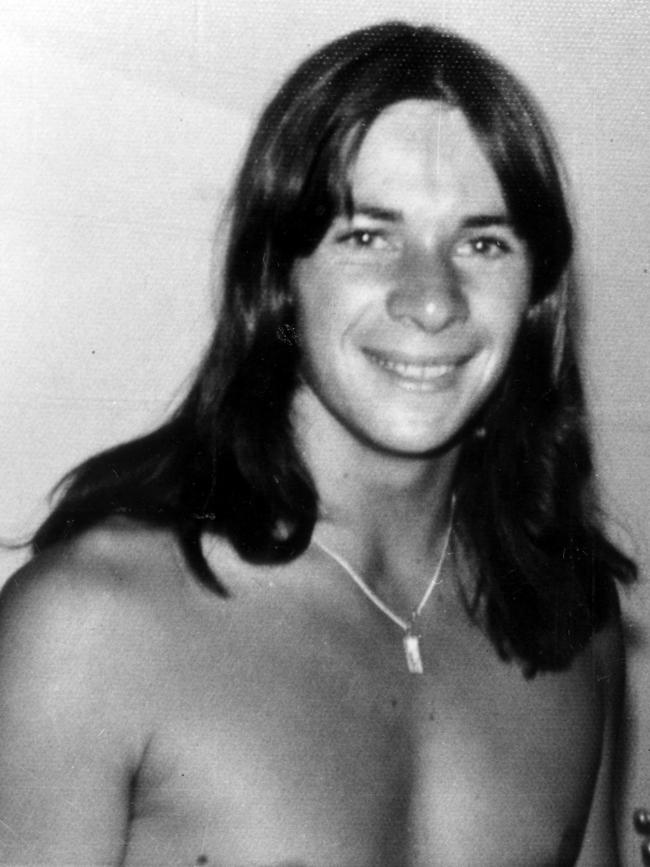

In the late 1970s, the depraved careers of Christopher Robin Worrell and Bevan Spencer von Einem peaked as they hunted the luckless in the shadows of a city otherwise known for its enlightened civility.

The city’s innocence had long been shot, but life was still sedate in a handsome, planned centre of gardens and churches that had avoided the scars of ’60s modernity. Then, as now, it was a cultural and culinary vibrant hub, with innovation bursting disproportionately from its modest population. And, in a socially adventurous turn, it had elected the flamboyant Don Dunstan as premier. No other state would have done that.

As Dunstan so wished, with his support of viticulture festivals and the arts, it had indeed become the Athens of the south.

But most of us knew not that much of Australia’s smallest mainland capital. Almost all South Australians live there, but for outsiders its shorthand was the Barossa Valley, to Adelaide’s north, the dandy Dunstan – and the missing Beaumont children.

I arrived there to work on its robust afternoon newspaper, The News, on Australia Day 1979 – precisely 13 years after the Beaumont children went missing. It was a move orchestrated by Dunstan as the first step on a path to joining the longstanding leader’s office (I never did).

That year would register two more reasons, and two more names, that help to distinguish, but never to fully understand, Adelaide: Truro and the Family Murders. And two more mysteries to ponder: one would soon be resolved, but the other lingers like an acrid, meteorological inversion permanently pushing down on the capital.

The year began with an odd, now-forgotten murder. A few weeks into the new job, I was editing the page one report of the murder of a Catholic “priest”, but the details were sketchy. For the second edition, we had his name: Thomas Butler. I knew him well. He was a Carmelite brother and had been art master of my school in Melbourne 10 years before.

Butler had picked up a hitchhiker near the Victorian-South Australian border on Tuesday, February 22, 1979, while driving from Melbourne to the order’s Adelaide headquarters. The young hitchhiker strangled Butler, put his body in the boot and drove 200km towards Adelaide, pulling off the Princes Highway at Meningie to dump the body by the side of the road, barely out of sight. He continued towards Mount Barker, where he was found asleep in the car by police, who quickly established he was not the owner. He freely admitted killing Butler and even went back with police to point out the body.

Within days, Adelaide would be in shock and searching its soul for answers as the deeds of a fierce serial killer unfolded. It was as if the devil had suddenly consumed this young man who, in the last weeks of his own life, unleashed an urgent orgy of death. Its first chapter had already been partly revealed but with a careless lack of enthusiasm police let it slip.

Truro to Adelaide’s north was named by Cornish miners after the cathedral town that acts as the capital of sorts for the county in England’s west that dips its toes into the Irish Sea; nothing could be further from the featureless, dry mallee bush of the Murray plains outside this dot beyond the Barossa. On Easter Sunday, April 15, 1979, bushwalkers found human remains there. That was a coincidence. A couple looking for mushrooms the previous Anzac Day had chanced upon a bone they thought might have been a cow’s leg. But it had a shoe on the end with a foot and painted toenails. They were Veronica Knight’s.

Police dismissively assumed Knight – who went missing on December 23, 1976, while Christmas shopping on Adelaide’s busy King William St – had run away and ended up outside Truro, perhaps dying of dehydration. Who would run away to Truro? Knight, 18, had tickets for a trip to Melbourne on Boxing Day. The hostel at which she was staying knew her to be so reliable and punctual they called police as her deadline to return passed. They were ignored.

Knight had been picked up at a bus stop by the volatile Worrell and his feeble, repugnant offsider, James Miller. Worrell raped and strangled Knight as Miller drove towards Truro. Worrell had been released from jail in October. He’d been caught because he boasted to a girl he would attempt to rape at knifepoint that he had been picked up speeding earlier in the day. In future, his victims would not live to tell.

Miller was gay, Worrell bisexual and they met in prison. They began by picking up gay men and beating and robbing them. Worrell decided to move on to girls and young women. In just 51 days, the handsome psychopath, in tandem with the limp, submissive Miller, would abduct, rape and murder seven girls, dumping most of the bodies outside Truro.

After the bushwalkers found 16-year-old Sylvia Pittmann’s body in 1979, police finally searched the area and found two more. They quickly drew up a list of seven girls and young women who had gone missing from Adelaide streets between late December and February 12, 1977. For several weeks, everyone in the city looked at fellow train passengers or people in the street wondering if the killer was among them. Adelaide was in shock and shame. How could we have missed this? The abrupt end to the murder spree came about when Worrell was killed in a car accident that February along with a girl the pair knew. Miller survived. In just the previous week, the two had abducted and murdered four women.

At Worrell’s funeral, Miller told a former girlfriend of Worrell’s it was probably a good thing that he had died because he had been raping and killing women. The woman contacted police two years later, when she read of the murders. On May 23, 1979, Miller was arrested and showed police to the other skeletal remains.

The enormity of the crimes and the fact seven victims in 51 days could be swept from the capital’s streets, yet no one other than their families noticed, unnerved Adelaide. But at least one of the killers was dead. Miller would be found guilty of murder and die in jail after many years.

But 25 days after Miller was arrested, the first of an unthinkably sinister series of abductions and murders took place – 1979 was not half over, yet another homicidal rampage was under way.

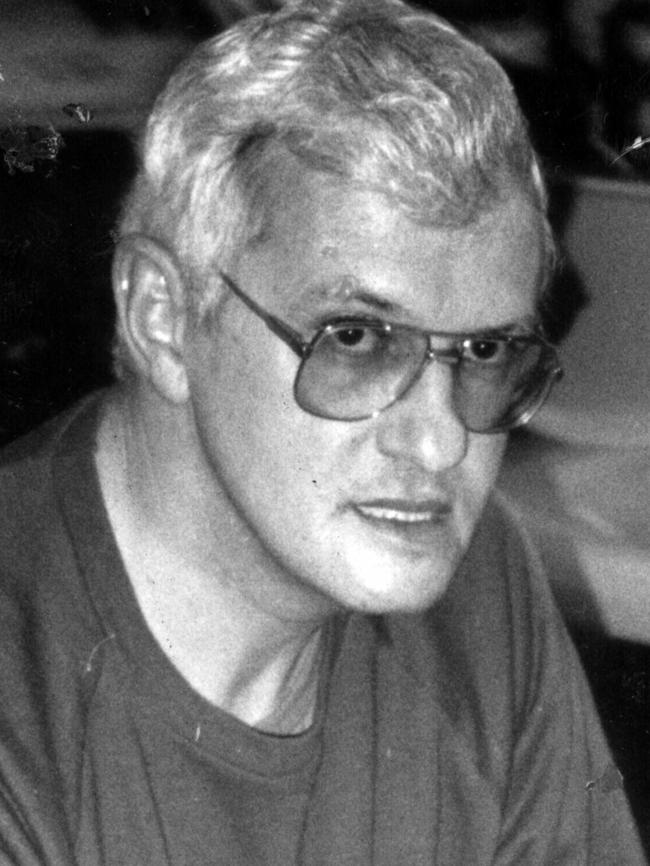

The victims would be boys and young men, but the brain-squirming evil driving it was a match. And at its centre was one man – von Einem. Unsuited to membership of humanity, the cruel von Einem violated even Adelaide’s conventions of random slaughter. Von Einem was a suburban accountant with pretensions to sophistication, and his balance sheet of wickedness presents a series of clues and “coincidences” that place him at or near the heart of other legendarily unsolved killings: the disappearance from Adelaide Oval 50 years ago on Friday of Joanne Ratcliffe and Kirste Gordon; at least five murders, possibly by a highly placed group of influential Adelaide citizens known as The Family; and even the abduction of the Beaumont children in 1966.

Worrell’s death robbed us of the chance to understand why that killer was seized by black moods during which he would scream abuse and lash out and kill. He was in one when he crashed his car and died. But while von Einem lives – he’s 77 – there is the outside chance that the key to so many of Adelaide’s secrets could be found. It would require adventurous legislation, but Australian states have traditionally allowed killers’ rights to trump those of victims and their families.

The twists of fate that unite von Einem with some of the nation’s most mysterious crimes are striking. And right now he is kept from us by the gates and wires of Yatala Labour Prison in Adelaide’s north, not far from the scenes of some of his crimes and which also houses John Justin Bunting, who is serving 11 life sentences for the Snowtown bodies-in-the-barrels murders.

The so-called Family Murders were abductions during which victims were drugged and sexually tortured, sometimes for days, at least one for weeks, by a group of pedophiles. The victims were picked up hitchhiking or snatched from the street in grabs almost certainly involving more than one offender. Most victims were taken at the weekend – The Family members probably worked Monday to Friday. The bodies were dropped over fences and, at one point, from a bridge. This might have also involved more than one offender – or a fit, well-built man. Like von Einem.

Alan Barnes, 16, was their first victim. He accepted a ride while hitchhiking on June 17, 1979, a Sunday, with perhaps four people already in the vehicle. His mutilated body was found seven days later showing traces of a sedative, Noctec, doctors use to calm patients before surgery.

Neil Muir, 25, was next two months later, turning up in a series of bags in the river at Port Adelaide. His body had been expertly dissected, his organs removed and his limbs inserted into his abdomen. Noctec was in his system. Von Einem knew Muir. So, too, did the well-connected doctor Peter Millhouse, who was charged and acquitted of murdering Muir.

Peter Stogneff was just 14 when he disappeared two years to the day after Muir. His body had also been dissected, but it was not found for more than a year, during which time a farmer had burned off the scrub where it had been dumped, and so it yielded few clues.

Months after Stogneff was found, Mark Langley, 18, was abducted – on a Sunday – and tortured, his body turning up nine days later. Someone had operated on his lower stomach, removing part of his bowel. The sedative Mandrax was in his system. Mandrax – made infamous by comedian Bill Cosby’s court cases – was no longer prescribed but von Einem had stocks.

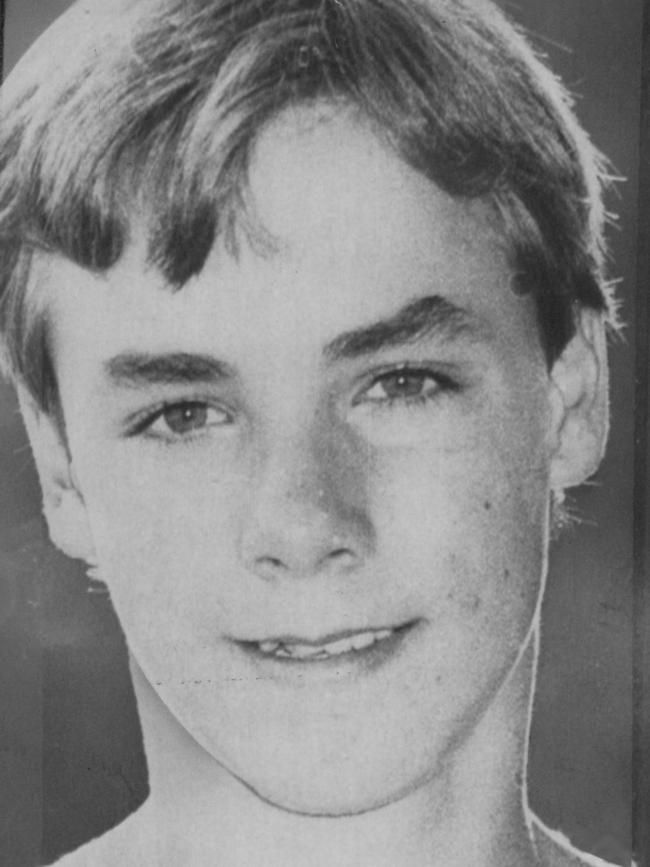

The last of the known victims was 15-year-old Richard Kelvin, the son of Adelaide’s Channel 9 news presenter Rob Kelvin. He was grabbed metres from the family home on a Sunday evening in June 1983, almost certainly by more than one abductor. It is known that von Einem held Richard Kelvin at his home for at least part of the five weeks before the boy’s body was found. It had traces of four drugs, including Noctec and Mandrax. All of the victims died of blood loss from anal injuries (but the cause of Stogneff’s death could not be ascertained) and each victim was washed after death and redressed in the clean clothes in which they had been abducted.

The database of those who had been prescribed by-then-rare Mandrax threw up a name: “B. von Einem”. He was tried and convicted of Kelvin’s murder. Later he faced charges of having murdered Barnes and Langley and in sensational evidence a “Mr B” claimed that he and others had been in the company of Barnes and von Einem before the murder. Both later cases hit hurdles and the prosecution withdrew the charges. It was Mr B who first drew attention to what he claimed were von Einem’s links to the Beaumonts and the girls at the Adelaide Oval.

In 2019, Lewis Turtur, a man whose name had been suppressed for decades and a former associate of von Einem, admitted that in the ’70s he had allowed von Einem to bring drugged boys to his apartment, where they had been abused by others. Turtur, whose brother is Olympic gold medal cyclist Mike Turtur, said his house guests, both now dead, would “take turns” with the victims. Turtur said the boys all left his place alive.

In 2014, the diaries of an associate of von Einem were found after the man had died. In them, Trevor Peters, who had died the year before, described encounters with the killer and his associates, one of whom was a neighbour.

At one point, a smirking von Einem was in an adjoining room speaking with his hairdresser. Peters could hear them giggling, “Oooh, how evil, oooh, it’s evil”. Intrigued, Peters parted the curtain and found von Einem with photographs of a drugged, naked boy in a car. “Just a hitchhiker,” he was told. He would later learn this was Barnes. It was reported that the hairdresser and von Einem jointly rented an apartment to which they took victims. Both men lived with their mothers.

The diaries included at least two names South Australian police had already linked to The Family and details of a woman Peters named telling him the Kelvin boy had been held there with several other visitors. The hairdresser had cut Kelvin’s hair, which correlates with a report from the time.

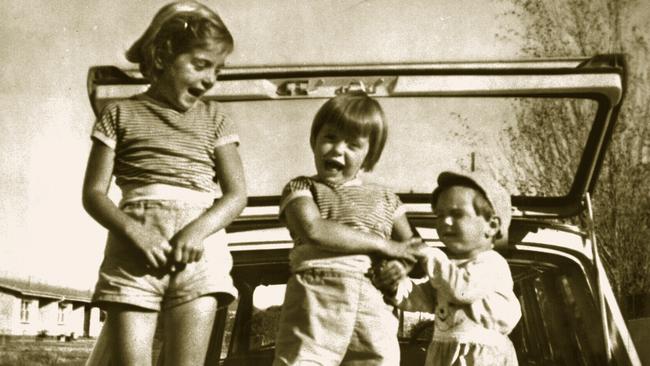

But von Einem’s links to infamous crimes go right back. Some people thought he was the tall, blond young man they had seen at Glenelg Beach on Australia Day 1966, the afternoon Jane, 9, Arnna, 7, and four-year-old Grant Beaumont went missing, although the photofit constructed by others was of an older man with a thin face.

In 2007, police reinterviewed von Einem about that infamous day after Channel 7 found footage of a crowd watching police divers checking drains at Glenelg. A man strikingly similar to von Einem is seen near a fellow whose appearance is close to that photofit.

On August 25, 1973, Joanne Ratcliffe, 11, and Kirste Gordon, 4, disappeared from the Adelaide Oval during a football match between Norwood and North Adelaide. They had been at the match with relatives who knew each other but the girls had not met until that afternoon. They left their seats for a toilet break at 3.45pm and over the next hour or so were sighted several times, once possibly distressed with a man carrying Gordon.

In January 2013, Adelaide’s The Advertiser revealed a hitherto unknown connection between this unsolved crime and von Einem. One of the adults with the girls that day was known only as Frank. Some years later, “Frank” would sell his suburban home to von Einem’s mother.

On May 10, 1972, another never-solved case rocked Adelaide. Law lecturer George Duncan and a friend, Roger James, were bashed on the banks of the Torrens River and thrown in, reportedly by off-duty vice squad members. The river bank was a regular haunt for gay men in the city where homosexuality was still unlawful. Duncan drowned, but James managed to crawl out with a broken bone in his leg. Once he made it to the road, a good Samaritan stopped, helped James into his car and drove him to the Royal Adelaide Hospital. It was von Einem.

Some time after Worrell’s burial, a headstone appeared stating “Untold love and joy he brought to all”. That’s what happens when justice fails us.

When, a couple of years ago, a man police long considered part of The Family died, it was written of him: “A beautiful man, very compassionate and caring.”

Parents and even siblings of The Family’s victims are dying. So, too, are members of The Family. They know who they are, and so does von Einem.

As the law stands, our hands are tied. Were von Einem, who is ill with diabetes, to be administered Sodium Pentothal, it is quite likely he would spill information on members of The Family. He might give clues to his possible role in the Beaumonts’ and the Adelaide Oval abductions – perhaps even the final resting places of those children (both Beaumont parents, Jim and Nancy, have died, Jim just this year).

But that would take a change to the law and a bold Attorney-General able to withstand the hackneyed claims of torture that would accompany a plan to forcibly use chemicals to get the truth from some of our worst criminals.

High-profile criminal defence barrister and former crown prosecutor Margaret Cunneen SC believes it is time for a change and for us to consider using chemicals to extract important information from people such as von Einem.

“What a great idea,” she says of the notion that a law could be introduced that would protect a prisoner’s right not to give evidence against themselves but also would allow for the use of a drug, such as Sodium Pentothal, to seek the vital secrets they keep.

She insists that we can never compromise the right not to incriminate oneself. And she likens it to the practices of the various ICAC-like bodies “where you have to answer but you have a protection … that evidence you give yourself can’t be used against you in criminal proceedings”.

“I think such an idea may find some favour now … I think there should be a campaign for it,” she says.

Von Einem has not yet applied for parole after the SA government introduced laws that give the Attorney-General power to deem a prisoner a dangerous offender, never to be released.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout