Chinese mining magnate Sally Zou fends off $10m legal claim

Enigmatic Chinese mining identity and Liberal party mega-donor Sally Zou has fended off a $10m legal claim, but has demonstrated an “inability to act truthfully and honestly’’.

Enigmatic mining magnate and generous Liberal Party donor Sally Zou has prevailed in a court case brought by a commodities trader who claimed she owed him at least $10m in commissions for hundreds of millions of dollars worth of trades he set up.

However Ms Zou has not escaped from the legal wrangle unscathed, with the Federal Court’s Justice John Halley saying in his judgment she had demonstrated a “marked inability to act truthfully and honestly’’, and some aspects of her evidence was “troubling’’ and “inexplicable’’.

The trades at the heart of the matter, in commodities such as coal and iron ore, never eventuated, however the trader, Anthony Smyth, claimed this was due to Ms Zou’s actions, and he was still owed the commissions.

The case, which was heard in the Federal Court in May and July last year, has now been dismissed, with Mr Smyth ordered to pay Ms Zou’s costs.

The documents filed in the case, which was heard over a number of days of at-times shambolic court hearings, due largely to Mr Smyth being self-represented, painted a picture of a relationship which started with the promise of mutual, vast enrichment, and ended with acrimony.

During the case Ms Zou called Mr Smyth a liar, and was also granted relief from Judge John Halley who presided over the case, allowing her to give evidence about a fraudulent HSBC bank document her affidavit evidence says she bought in Hong Kong that was to be used to establish her bona fides with coal buyers.

Ms Zou characterised Mr Smyth as someone who frequently sought to borrow money for her, and denied his claim to any payment, or to the assertion that he’d been instrumental in setting up relationships with companies such as BHP.

Sally Zou, the Liberals, and court

Ms Zou has been a mysterious figure since coming to the notice of the public some years ago because of her large donations to the Liberal Party at the state and federal level – more than $700,000 in 2021-22 alone – due to her occasional brushes with the legal system, and her former penchant for placing full page advertisements in national and local newspapers extolling the virtues of the Liberal Party – and in once case looking for a house to buy.

On one occasion in 2015, Zou published a full-page advertisement in The Australian thanking “Auntie Julie Bishop”, “Uncle Tony Abbott” and “Uncle Li Huaxin, Consul General of China”, and also once welcomed former Liberal prime minister Malcolm Turnbull to Adelaide with a full-page advertisement.

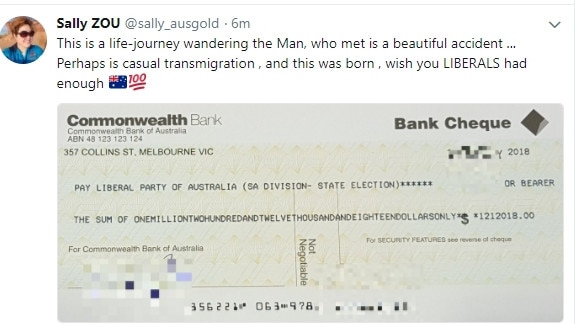

Another time she caused a headache for former SA state premier Steven Marshall by tweeting an image of a $1.2m cheque made out to the Liberal Party, captioned: “This is a life-journey wandering the Man, who met is a beautiful accident … Perhaps is casual transmigration, and this was born, wish you LIBERALS had enough”.

It later emerged the value of the cheque – $1,212,018 – corresponded with the date of Mr Marshall’s 50th birthday. The money in that case never appears to have actually been donated to the Liberal Party.

Ms Zou divides her time between Adelaide, where her daughters go to school, and Sydney.

The source of her wealth has never been revealed however, and while she has diverse business interests, including previously owning a gold operation in New South Wales – shuttered by the mining regulator after the identification of an illegal dam and the death of more than 25 kangaroos – she has also been the subject of numerous disputes for non-payment and contractual matters.

These include her allegedly backing out of a deal to buy a $5.6m mansion on one of Adelaide’s most prestigious streets, and a dispute over payment for 32 tonnes of cherries bought for export – a matter which was settled shortly before Ms Zou was due to take the stand in South Australia’s Supreme Court to explain why signatures on financial statements did not appear to match.

In the house matter, Ms Zou asked the Supreme Court in South Australia for a closed hearing due to her “public profile” – a request which was denied.

During court hearings over the cherry dispute, Ms Zou’s lawyer claimed the case was an “abuse of process” designed to “have her affairs exposed in the media’’.

Her lawyer, Simon Ower, accused the cherry company’s lawyer, Brendon Roberts KC, of “grandstanding” for the media and suggested to the court that materials were being provided to News Corp Australia.

Mr Roberts had been seeking in that matter to cross examine Ms Zou over the solvency of her company and the fact that signatures on two financial documents purported to have been signed by Ms Zou did not appear to match.

“My submission will be that one or other is a forgery,’’ he told the court.

Mr Roberts clarified that he wasn’t arguing Ms Zou had forged anything, but that one of the signatures might be a forgery.

That matter was settled out of court before Ms Zou was due to take the stand.

Partnership over $700 bottle of wine

In the most recent matter, Mr Smyth claimed in documents filed with the court, that he set up several commodities deals – cumulatively worth hundreds of millions, if not billions of dollars – but alleged Ms Zou’s actions led to those agreements falling through and his reputation in the industry being irrevocably damaged.

The relationship, Mr Smyth alleged, started auspiciously, with a deal sealed over a bottle of 1996 Hill of Grace that would make both of them, allegedly in Ms Zou’s words, “very rich”.

Smyth’s statement of claim alleged he met Ms Zou in 2011 – something later disputed in court.

At the time, he said, he had recently landed a plum role working for Ningbo Development and Investment to run its Australian procurement.

He was, he said, approached by an associate of Ms Zou – John Li – who convinced him to meet with her to talk about possible opportunities.

To hear him tell it, Mr Smyth mightily resisted the initial overtures, having just been employed in a senior role he had been working towards for years.

Mr Smyth said Mr Li told him that Ms Zou’s family were “big end-users in China. They’re very famous. Sally has a lot of money.’’

Ms Zou was insistent, he alleged, claiming there were deals worth millions of dollars to be had.

“Work with me, and together we will be very rich,’’ she told him, according to Mr Smyth’s claim.

During an initial meeting at Kamfook restaurant in Sydney’s Chinatown, Mr Smyth said Ms Zou told him she wanted to buy mines and commodities. She talked up her connections in China.

“I did many trades in China,’’ Smyth recalls Zou saying.

“My uncle is one of the biggest businessmen in China with Sinosteel and also in cement. He is involved with me and is helping me a lot here now. I want to put the trades through my company and sell back to China.’’

Smyth says he wasn’t interested to begin with, and warned Ms Zou getting involved in bulk commodities trading in Australia was no small matter.

“Sally you need to understand that trading in Australia is different,’’ Smyth’s affidavit, documenting the conversation, alleges.

“It’s OK. I have got money Anthony. I will not fail,’’ Ms Zou is alleged to have responded.

Mr Smyth was eventually won over, and the deal was celebrated at the Zilver restaurant in Haymarket, where Ms Zou asked him to pick his favourite wine for a toast. A $699 bottle of Hill of Grace was cracked, and Ms Zou toasted to “a long and prosperous future together’’.

“My uncle is the biggest,’’ Ms Zou allegedly told him.

“In China, we are number one.”

Zou’s funding for deals failed, court told

Mr Smyth says he went on to organise several deals, showing Ms Zou around coal export operations in Newcastle, and lining up contracts with major global players including Glencore for the supply of significant amounts of commodities.

All of those deals, Mr Smyth told the court, fell over due to Ms Zou’s failure to pay, leaving him out of pocket for significant expenses incurred by himself and his team in setting up the deals, for millions in expected commissions, and leaving his reputation in tatters.

“I secured the commodities for the trades, and on no occasions did … Ms Zou produce the money and she was the sole reason for the failure of each trade. I did all that I had to your honour,’’ Mr Smyth told the court last year.

He also told the court he believed Ms Zou had the financial capacity to make good on her claims because he was shown a document he understood to show her company had $US18.6bn ($26.6bn) in its accounts and that she personally had $US120m.

He also said he had been told by Ms Zou that her uncle was highly placed in companies including China Southern Cement and Sinosteel – a claim Ms Zou rejected while also noting that “uncle” was being used as a term of respect, as is common in Chinese culture.

Mr Smyth told the court that while he held up his end of the bargain, Ms Zou’s failure to pay for the commodities he sourced and fulfil contracts led to the collapse of deals worth hundreds of millions of dollars, leaving him personally several million out of pocket on commissions.

Ms Zou’s defence to Mr Smyth’s claim broadly rejected all of his claims.

Her affidavits painted a picture of Smyth as someone who pursued her to be his business partner – rather than the other way around. Ms Zou claimed he would borrow money off her for personal reasons.

“Once he told me he did not have dinner money, he wanted to borrow $100,’’ Ms Zou’s affidavit, sworn via an interpreter, says.

“Next thing I observed that he walked into a pub and bought drinks with two females.”

Ms Zou says in her affidavits that she first came to Australia in 2006 on a business visa looking for education projects.

In late 2010 she started looking for commodities ventures and made $2m setting up deals for Chinese clients.

She agreed that she and Smyth worked together as partners to find deals for her Chinese clients, but says their businesses were separate, and that he was never her employee or co-shareholder.

The deals fell over for various reasons – the drop in the price of coal in the case of a deal with Glencore, she alleged.

“I did not and have not any political connection to China,” she says in her affidavit. “I had been invited in various venues and had photos with politicians. That was all I had.”

Doubt whether agreement even existed

The case was complicated by the fact that Mr Smyth had, he said, had lost many of the relevant documents through IT misadventure, and at one point, when challenged to do so, he was unable to put an exact dollar figure on what he was claiming to be owed.

And while Mr Smyth in court characterised Ms Zou’s actions as “premeditated fraud”, her lawyers argued it was difficult to establish that an agreement existed between the two at all.

“I guess in short, the case can be summed as (a) premeditated, calculated series of fraud and misleading and deceptive conduct,’’ Mr Smyth told the court in July.

Ms Zou’s lawyer, Phillip Lonergan, said in his closing submissions said that a “working agreement’’, which Mr Smyth had based much of his case around, was vague and unspecific.

“Therein lies the problem because the contract or working agreement becomes very difficult to interpret in any way that gives any sensible meaning to what the parties objectively could have intended,’’ he said, adding that it was difficult to ascertain who was acting in what capacity, and in the case of one contract it was “not clear from the document itself who the parties to the contract are’’.

Justice Halley ruled that Ms Zou was not liable to pay the commissions and said in his judgment that “the alleged procurement contracts providing for the payment of specific commissions … by Ms Zou or her associated entities have not been established’’.

He also said he was unable to give “any significant weight” to Mr Smyth’s evidence, saying that there was a long time between the swearing of his affidavits and the conversations they purported to document.

“They are set forth in a level of detail and precision on critical aspects of the claims that he advanced that is implausible,’’ Justice Halley says.

“Mr Smyth found giving evidence in cross-examination a confronting experience. His answers were all too often, non-responsive, argumentative and long winded. This caused him to give evidence that was inconsistent with his affidavit evidence and earlier evidence given in cross-examination.

“Further, the weight that could be placed on Mr Smyth’s recollection of events was also put into question due to his frequent inclination to act as an advocate in his own cause in the course of his cross examination by counsel for Ms Zou.

“I do not doubt that Mr Smyth genuinely believed he was answering questions truthfully to the best of his recollection, but for the foregoing reasons, I consider that his recollections were unreliable.’’

Justice Halley said Mr Smyth’s cross examination of Ms Zou was also problematic.

“Mr Smyth experienced great difficulty in recognising the distinction between making submissions and asking questions and at times, the cross-examination descended into an exchange of insults,’’ Justice Halley says.

“Nevertheless, Ms Zou’s acknowledgment that she had procured the forged HSBC confirmations for herself and (the company) AGE, reflected poorly on her credit.

“She claimed in her affidavit evidence that Mr Smyth suggested to her that she purchased forged bank documents to demonstrate her access to funds.

“Even if that suggestion had been made by Mr Smyth, a suggestion I am not persuaded was in fact made, the purchase and provision of the forged HSBC confirmations to the supplier counterparties to the commodities contracts demonstrates a marked inability to act truthfully and honestly.’’

Justice Halley also said some of Ms Zou’s evidence was “troubling and “inexplicable”

Ms Zou said via a spokesman this week: “While these claims were distressing to Ms Zou and her family, she is glad they are now resolved’’.

Mr Smyth said he was assessing his legal options.