Who is Sally Zou? This court case may finally provide some answers

A spat over a deal gone awry might provide a glimpse into the world of the major political donor, with alleged ties to some of China’s most powerful business figures.

It started auspiciously – a deal sealed over a bottle of 1996 Hill of Grace which would make commodities trader Anthony Smyth and his new business partner Sally Zou “very rich”.

A decade later, Smyth finds himself in the Federal Court, chasing Zou for more than $10m in commissions, expenses and damages – millions of dollars she denies he has any claim to.

Zou had led Smyth to believe her company had $US18.6bn ($26.2bn) in the bank – and that she had another $US120m personally – he alleged. The documents backing up Zou’s claims were a “beautiful forge”, he was allegedly later told.

Zou has, since those early meetings in 2012, built a considerable public profile as a prolific Liberal Party donor and financial backer of the Port Adelaide Football Club.

Her colourful interactions with politicians on both sides of the aisle has raised her profile – and eyebrows – further. On one occasion in 2015, Zou published a full-page advertisement in The Australian thanking “Auntie Julie Bishop”, “Uncle Tony Abbott” and “Uncle Li Huaxin, Consul General of China”.

Despite the donations – some $1.7m to various Liberal Party branches across the country since 2015 under her own name or through her companies including the Aus Gold Mining Group – little is known about the source of Zou’s wealth or why she decided to settle in Australia in the first place.

In some ways, the spat over a deal gone awry may be the best chance to shed light on Zou – who divides her time between Sydney and Adelaide – her fortune and her business dealings.

Zou, the Federal Court heard this week, told Smyth she was directly related to a senior executive at Sinosteel, one of the world’s largest mining and steelmaking companies and a state-owned enterprise with direct links to the upper echelons of the Chinese Communist Party.

Court case

That assertion has yet to be tested in court, and Zou declined to respond to questions, as did Sinosteel.

But that claim, Smyth told the Federal Court, was what gave him the confidence to represent Zou in talks with some of the world’s largest commodities houses – including Glencore and BHP – setting up deals worth hundreds of millions of dollars, which should have netted them both a fortune.

Each of those deals fell flat, Smyth said, because Zou failed to make good on the payments for commodities including coal, iron ore and diesel – all purportedly sourced on behalf of her uncle and his vast interests in China.

“I secured the commodities for the trades, and on no occasions did … Ms Zou produce the money and she was the sole reason for the failure of each trade. I did all that I had to your honour,’’ he told the court on Monday.

Smyth met Zou in 2011. At the time, he had recently landed a plum role working for Ningbo Development and Investment Group to run their Australian procurement.

He was, he said, approached by an associate of Zou – John Li – who convinced him to meet with her to talk about possible opportunities. To hear him tell it, Smyth mightily resisted the initial overtures, having just been employed in a senior role he had been working towards for years.

Li told him, he says, that Zou’s family were “big end-users in China. They are very famous. Sally has a lot of money.’’

Zou was very insistent, he alleged, claiming there were deals worth millions of dollars to be had.

“Work with me, and together we will be very rich,’’ she told him, according to documents filed by Smyth with the court.

During an initial meeting at Kamfook restaurant in Sydney’s Chinatown, Smyth says Zou told him she wanted to buy mines and commodities. She talked up her connections in China.

“I did many trades in China,’’ Smyth recalls Zou saying.

Family ties

“My uncle is one of the biggest businessmen in China with Sinosteel and also in cement. He is involved with me and is helping me a lot here now. I want to put the trades through my company and sell back to China.’’

Smyth says he wasn’t interested to begin with, and warned Zou getting involved in bulk commodities trading in Australia was no small matter. “Sally you need to understand that trading in Australia is different,’’ Smyth’s affidavit, documenting the alleged conversation, says. “In Australia there are strict take-or-pay policies. If you do not take the shipment in the laycan period, then you are still charged often close to one million for port costs, let alone everything else.

“It’s okay. I have got money Anthony. I will not fail,’’ Zou is alleged to have responded.

“Sally that is good. But everyone in this industry has money. Big money. It is a global market. The sellers will want to be satisfied that you are a genuine buyer,” Smyth told her.

Smyth was eventually won over, and the deal was celebrated at the Zilver restaurant in Haymarket, where Zou asked him to pick his favourite wine for a toast. A $699 bottle of Hill of Grace was cracked, and Zou toasted to “a long and prosperous future together’’. “My uncle is the biggest,’’ Zou allegedly told him. “In China, we are number one. Work with me, and together we will be very rich.’’

Smyth says he went on to organise several deals, showing Zou around coal export operations in Newcastle, and lining up contracts with major global players including Glencore for the supply of significant amounts of commodities.

All of those deals, Smyth is arguing in the Federal Court, fell over due to Zou’s failure to pay, leaving him out of pocket for significant expenses incurred by himself and his team in setting up the deals, for millions in expected commissions, and leaving his reputation in tatters.

The affidavits in the matter include correspondence purportedly from senior executives at companies including Glencore and shipping company Sanko – all increasingly concerned about Zou’s failure to make good on the payments.

One email correspondence from a Sanko lawyer says the “continued silence” from one of Zou’s companies, Australia Gloria Energy, “particularly in the face of serious allegations that they do not intend/cannot perform, is both commercially extraordinary and unacceptable’’.

Sanko later took that matter to court and was awarded $US706,105 and costs for the company’s failure “to provide or load the cargo or any other cargo within the contractually agreed time frame or at all’’.

In a telephone call with Glencore’s then-head of coal, Avi Spyrides, Smyth says he was told it was a “serious situation’’. “You have no letter of credit for the cargo,’’ Spyrides is said to have told him.

Inner workings

Smyth’s affidavits document numerous assurances from Zou during this time.

“Do not worry darling,’’ one reads. “I think we can win in 2013 … you are very smart and handsome, I have a big market in China, so we are a very good team and partner,

“Hearted regards!, Sally.’’

Smyth, for his part, was getting increasingly worried.

On September 9, 2012, he wrote: “Sally, you have failed on five contracts you have signed and sealed and failed to perform on. (On) top of this you owe millions for a contract in Newcastle coal alone, you also owe me a considerable amount of hundreds of thousands of dollars is (sic) real costs, lost revenue and commissions.”

“I also lost several staff and my work property due to you,” the email reads. “Before anything, when are you going to pay this back firstly as you said?’’

Zou’s defence to Smyth’s claim broadly refutes all of his claims. She is seeking to have the matter dismissed.

When asked this week about her relationship to a senior Sinosteel executive, Zou said: “This matter is in dispute before the court and I will be vigorously defending myself against these false claims, but it would be inappropriate for me to comment further at this time.”

Her affidavits are more fulsome, painting a picture of Smyth as someone who pursued her to be his business partner – rather than the other way around. Zou claims he would borrow money off her for personal reasons.

“Once he told me he did not have dinner money, he wanted to borrow $100,’’ Zou’s affidavit, sworn via an interpreter, says. “Next thing I observed that he walked into a pub and bought drinks with two females.”

Humble start

Zou says in her affidavits that she first came to Australia in 2006 on a business visa looking for education projects.

In late 2010 she started looking for commodities ventures and made some $2m setting up deals for Chinese clients.

She agrees that she and Smyth worked together as partners to find deals for her Chinese clients, but says their businesses were separate, and that he was never her employee or co-shareholder. The deals fell over for various reasons – the drop in the price of coal in the Glencore case, she alleges.

“I did not and have not any political connection to China,” she says in her affidavit. “I had been invited in various venues and had photos with politicians. That was all I had.”

The imbroglio with Smyth is not Zou’s first difficulty.

In 2017, she found herself at the centre of a stoush over political donations and Chinese influence after then foreign minister Julie Bishop was forced to deny she had any involvement in the Julie Bishop Glorious Foundation, a company established by Zou. (It was later renamed the Glorious Foundation.)

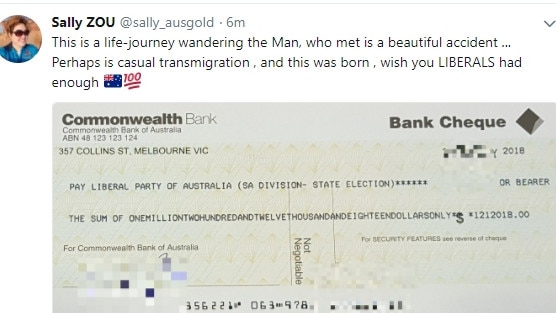

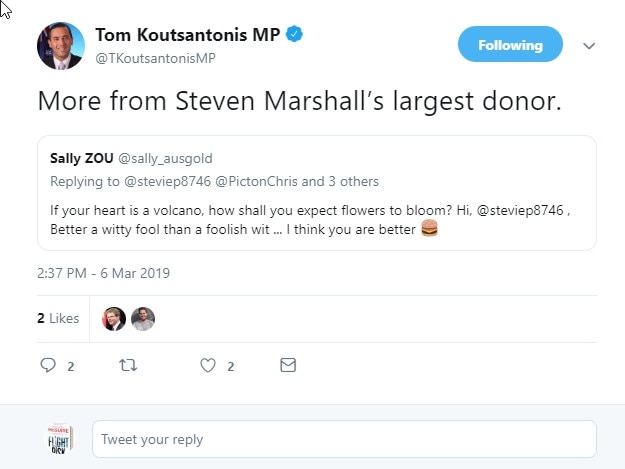

Some months later, Zou posted an image of a $1.2m cheque made out to the Liberal Party on Twitter, writing: “This is a life-journey wandering the Man, who met is a beautiful accident … Perhaps is casual transmigration , and this was born , wish you LIBERALS had enough”. It later emerged the value of the cheque –$1,212,018 – corresponded with then South Australian premier Steven Marshall’s fiftieth birthday.

Then there was AusGold’s sole Australian mining operation – the Good Friday gold mine near Tiboobura, in northwest NSW, which was ordered to shut by the state’s resources regulator after it identified an illegal dam and the death of more than 25 kangaroos at the site. AusGold later collapsed, with Zou claiming she was owed some $35m.

She purchased the mine in 2015, but wrote in the Federal Court filings that mining was not a focus in 2012 and 2013 – when she first went into business with Smyth.

She also denies the conversation between the two about her personal fortune ever happened. “I did not agree that conversation happened,’’ she says. “I would not tell Smyth how much money I had in the bank account at the first meeting.

“All I have left in memory was that Smyth was eager to join force with me and John, he would be responsible to find suppliers in Australia; I would be responsible for finding the Chinese buyers.’’

Ms Zou also says in her affidavit that she “bought a bank statement’’ for $HK100,000 ($17,930), after Li suggested that without one to represent her financial strength “no company will open the door to you’’.

Ms Zou denies she was ever asked to pay any money by Smyth, nor informed that there were costs to be met. Instead, she says in her affidavit, that Smyth would ask her to lend him money, which he would promise to return the next day.

The matter was set down for trial for four days. It sat for just one. It is scheduled to return to court on Monday.