READ MORE: The discerning eye of a nation’s curator: obituary by Grazia Gunn

I defended my assessment, and thought the conversation would finish there. But then he asked if I would be interested in helping him to mount an exhibition of “a post-impressionist artist”. This turned out to be Vincent van Gogh, and I ended up spending some months as a visiting curator at the NGV, in Mollison’s immediate entourage, learning a great deal about how a museum works, as well as about the man himself.

Among the stories Mollison told me was one about his start at the NGV, when he had called on the formidable Ursula Hoff, probably the most scholarly curator the gallery has ever had. Hoff took young James into the print room, opened some folios of old master engravings and etchings, and told him to come back to her office when he had finished.

Needless to say, fascinated by the treasure that had been opened to him and at the same time fearing Hoff’s scorn if he should declare himself to have “finished” with them, he remained at his desk until she rescued him at closing time.

Shadowing Mollison around the gallery when I was not researching van Gogh and designing a rationale for our exhibition, I encountered other young proteges who today occupy various eminent posts in the art world.

I once watched Mollison deal with a senior curator who had brought in some items as recommended purchases. He listened to the case the curator made for each of about eight items, then unhesitatingly — and with a Louis XIV-like assurance — nominated the three the gallery would buy.

Afterwards he explained to me that he always sought to surround himself with people who had deeper specialist knowledge of particular areas of the collection, but considered his own particular skill to be first in picking these people and then in making the decision about which acquisitions would best contribute to building the collection.

Building a collection was of course Mollison’s great achievement. For years before the opening of the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra, and with the assistance of a talented board that included learned artists such as James Gleeson, he had worked behind the scenes to build a new collection for the nation.

Given his success in this endeavour, I was disappointed that he was able to obtain so few of the loans I had recommended for our van Gogh exhibition. But it is one thing to travel around the world with an open chequebook, and another to ask galleries to part with their precious collections and allow them to travel to the Antipodes.

At the time I felt Mollison could have tried harder, but in hindsight he undoubtedly remains, with Edmund Capon, one of the two most significant Australian public gallery directors of recent decades.

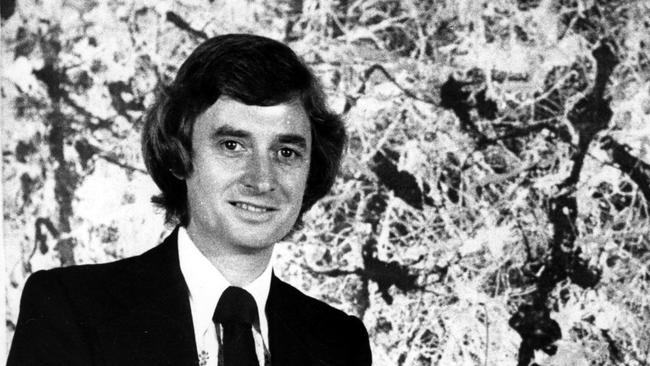

Many years ago, when James Mollison was director of the National Gallery of Victoria, he rang unexpectedly to tell me that he thought my review of the Rupert Bunny retrospective had been too harsh.