Cezanne the greatest influencer in the National Gallery of Australia’s new blockbuster

The National Gallery of Australia’s new blockbuster exhibition traces connected developments in Australian art with those in Europe, from Cezanne and Giacometti to Russell Drysdale and Grace Cossington Smith.

The Museum Berggruen collection, shaped and built by German art dealer Heinz Berggruen from the 1950s onwards, tells the story of the revolutionary changes in modern art in Europe. It is a story of artists who, through the exchange of ideas across generations, strove to displace tradition and see the world from new perspectives.

The National Gallery of Australia’s collection tells this story, too, but from a local context. By putting these two collections in dialogue, we can illuminate the astonishing speed with which ideas, techniques and people moved across national borders and geographic distances, connecting developments in Australian art with that of Europe through moments of contact and exchange.

While it is impossible to pinpoint a starting point for modern art, we begin with Paul Cezanne’s lifelong question of how to translate the act of looking into a picture.

This simple query became a source for countless and evolving questions that were shared among artists throughout the 20th century, forming a genealogy, or family tree, of influences that unifies the multiple and divergent concerns of modern art.

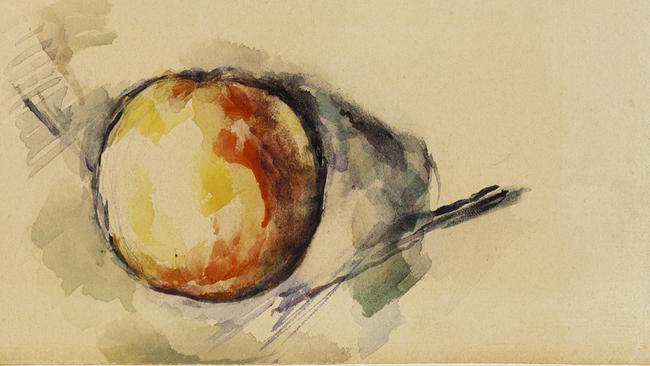

Cezanne was the artist who broke the grip of linear perspective in Europe and introduced a largely uncodified but subjectively truthful way of translating his observations into paint. Like most European artists, Cezanne was taught to paint and draw using single-point perspective and chiaroscuro modelling: Renaissance methods that create illusory depth and volume through plunging lines of perspective, and light and dark pigments to model contours.

But unlike most of these artists, he believed these conventional methods were a systematic exercise, techniques that amounted to “nothing more than a workman’s craft” and resulted in art that was “inartistic and common”. Cezanne chose a new departure for his art, a naive and sincere point of origin: to replicate only the sensations his eyes received and record these on canvas, glance by glance. This simple premise became a vital, lifelong and doubt-riddled pursuit that inspired transformations in perspective, colour and form in modern art.

By the mid-1870s, Cezanne’s work had developed in such a distinct direction, it appeared to discard all convention.

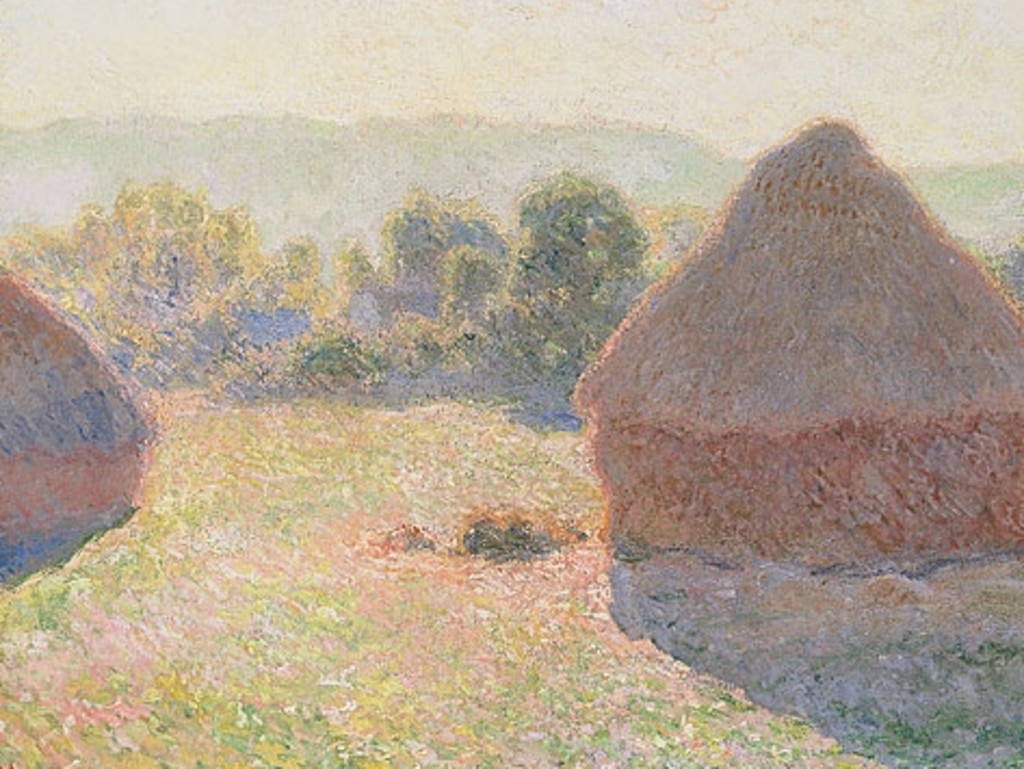

First, his compositions were not planned using single-point perspective but derived from his unique open-ended process: standing before his subject, whether a still life, landscape or portrait, he would take in the scene with widened eyes to understand its underlying structure. He spoke of grasping “a harmony between several interactions (aided by) a powerful organising mind”, and advised younger artists to “treat nature by means of the cylinder, the sphere (and) the cone” in building their compositions.

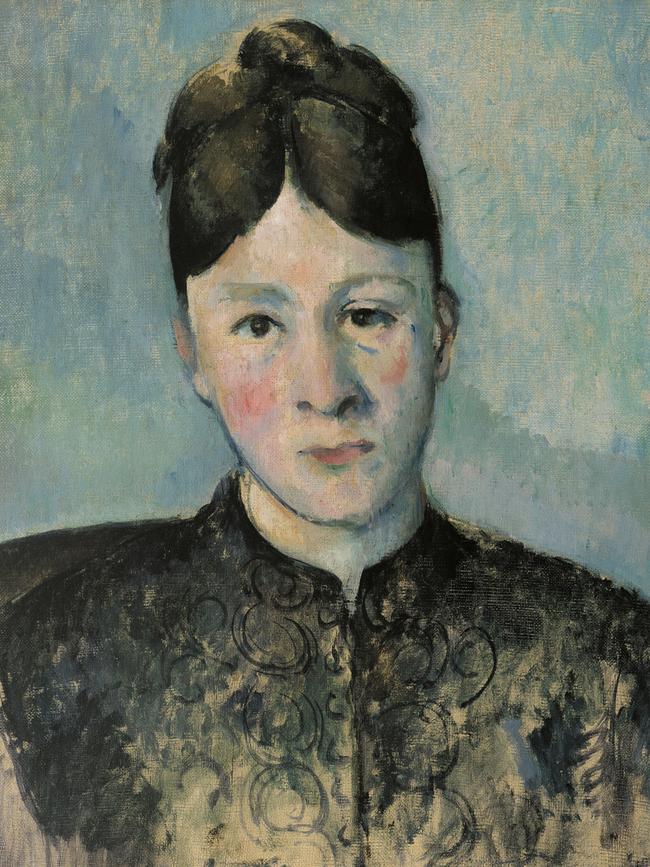

Whether depicting fruit or a head, he began to paint his first object from what he called its “culminating point”, usually at the centre or the point closest to the viewer’s eye, such as the bulging middle of an apple. Then he painted his way outwards towards its edges. A succession of glances translated the colour he perceived into hatched strokes of paint, consistently applied as “as if through a veil”. Having completed his first part of the composition, Cezanne seemed to arbitrarily choose where he would work next, as though it was an improvisation.

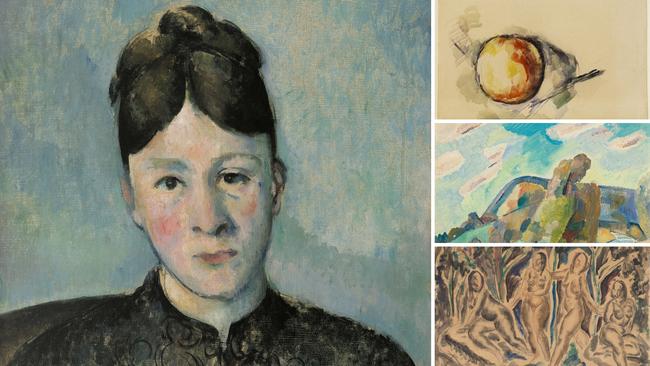

Critics RP Riviere and JF Schnerb observed this in 1905 and noted that it led to distortions of perspective, bare patches of canvas and unresolved edges of objects that caused parts of the foreground and background to dissolve into each other. Cezanne said he allowed these distortions to occur in the name of “sincerity”. His Portrait of Madame Cezanne c.1885 conveys many of these techniques.

Cezanne stated that he wanted to “make of Impressionism something solid and durable like the art of museums” but recognised that “all that we see dissipates, moves on. Nature is always the same, but nothing of her remains, nothing of what appears before us.” His method, uncodified and responsive to received sensations across a span of time, unravelled the orthodoxy of European art.

He found little recognition during his life, but his ideas proliferated among a new generation of artists in both Europe and Australia. The spread of his ideas came from direct encounters with his paintings and, as a sign of the rapidly developing technological times, encounters with his art through photographic reproductions.

The artists in the Museum Berggruen all looked to Cezanne for inspiration: Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque upturned linear perspective once more, Henri Matisse boldly reconsidered colour, Paul Klee sought out naive beginnings, and Alberto Giacometti applied Cezanne’s distortions to sculpture.

Artists from the NGA’s collection extend this family tree outwards: Roland Wakelin, Russell Drysdale, Ian Fairweather, Grace Cossington Smith, George Bell, Lina Bryans and John Passmore all grappled with Cezanne’s ideas in their work. Later, Dorrit Black, Grace Crowley, Anne Dangar, Roy de Maistre, Paul Haefliger and Eric Wilson took up the mantle of cubism, following in the footsteps of Picasso and Braque via the Salon cubists.

In Germany, Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack developed techniques alongside Klee, while Inge King fleetingly saw Klee’s work at the notorious and pejoratively titled Degenerate art exhibition before the outbreak of World War II. Both artists, among others, brought Bauhaus ideas to Australia, inspiring local artists such as Clement Meadmore to champion its principles.

Other Australian artists would encounter the work of European modernists while studying art in Europe. For example, Rosemary Madigan viewed Matisse’s work and it’s likely Bea Maddock saw Giacometti’s. They would hold on to the memories of what they saw and create work back in Australia that extended upon these European artists’ styles.

This genealogy of influence reaches far and wide, across space and time, and like a family tree it must also grapple with complexity.

For instance, while Dora Maar and Picasso’s relationship was relatively brief, the impact they had on each other’s work and lives endured. For artists, looking not only at the world around them but at other artists’ works for inspiration and guidance is fundamental. By extension, as we view their works, we may find that our way of seeing the world is changed too.

In his 1927 book Cezanne: A Study of His Development, artist, critic and Cezanne scholar Roger Fry noted how a generation of artists came indirectly to understand the French painter’s work. Fry stated that Cezanne’s radical techniques had quickly been absorbed, modified and disseminated by his contemporaries, so much so that in Cezanne’s works we “see not so much his expression as the distorted image of it, which has gradually taken its place in our own minds”. In early 20th-century Australia, this sense of distance was experienced through limited physical access to international avant-garde artworks and was an important factor in the local development of modern art. Until the late 1930s, Cezanne’s post-impressionist innovations were transmitted to the southern hemisphere primarily via reproductions of his works and mediated through contemporary critique. Through these indirect but nevertheless transformative means, Cezanne’s distinctive broken brushstrokes, skill in conjuring three-dimensional form through colour, and imaginative compositions filtered through Australian art schools and inspired new approaches to image-making.

Italian artist Antonio Dattilo-Rubbo’s atelier in Sydney was a locus of artistic talent where being receptive to new ideas, originality and an internationalist outlook were championed. Norah Simpson was a student of Dattilo-Rubbo, alongside the young painters Wakelin and Cossington Smith.

In 1913, Simpson, who had trained for a year in London at the Westminster School of Art and had seen examples of modern European art first-hand, returned to Sydney with books and colour reproductions of paintings by Cezanne, Matisse and Picasso in tow.

As Wakelin recalled in 1928: “Colour was the thing it seemed, vibrating colour – and there were new ideas in composition – unorthodox.” Together, colour and composition became generative tools in a new phase of art-making in Australia.

The arrival of these resources into Australia coincided with an increasing awareness of post-impressionism in artistic circles.

Through coverage in the mainstream media, artists were aware of the developments in painting exhibited in the landmark London exhibitions Manet and the Post-Impressionists (1910–11) and the Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition (1912) that were organised by Fry and were the first to position Cezanne as the instigator of new artistic paradigms.

Cezanne’s techniques and motivations clearly informed early efforts by artists now credited with creating the first modern paintings in Australia.

Wakelin extended Cezanne’s proto-abstract style even further and produced in this period a collection of paintings recognised for their early adoption of non-objective imagery and vivid experimentation with colour. In Wakelin’s Barn near Tuggerah 1919 for instance, the compositional potential of colour has been reimagined, as seen in the barn’s unexpected mint-green roof and flash of bright gold cutting through the field.

In later years, Cossington Smith’s love of the Australian landscape predisposed her to follow Cezanne’s strategy of meditating on the motif in situ: she stated that of all the painters she admired, “there aren’t any others that impress me like Cezanne”.

In Landscape c.1931, visible, multidirectional brushstrokes echo the construction of Cezanne’s works and bring the scene to life. Where Cezanne’s brushwork was often spare and quick – particularly in his depictions of Mont Sainte-Victoire near his home in Aix-en-Provence – Cossington Smith brought a more lyrical use of paint to her compositions. By laying bands of pure colour side-by-side across the canvas, she achieved an immediacy and vibrancy of vision that spoke directly to the environments she encountered.

The private art school established by Bell and Arnold Shore in 1932 provided a similar context in Melbourne for disseminating Cezanne’s technique. The Bell-Shore School echoed Cezanne’s concern for structure, solidity and order, placing a high value on form and design as means to reconcile “modernity with the timeless qualities of the classical tradition”, while promoting individual ways of constructing compositions that were fabricated rather than observed.

The Leonardo Art Shop was opened in 1928 by author Gino Nibbi in Collins Street, Melbourne, and became a catalyst for the practical application of modern ideals through the sale of international art books, magazines, prints and postcards of works by artists such as Cezanne, Matisse and Amedeo Modigliani. This was a combination Shore subsequently remembered as “a heady mixture, back in the late nineteen twenties”.

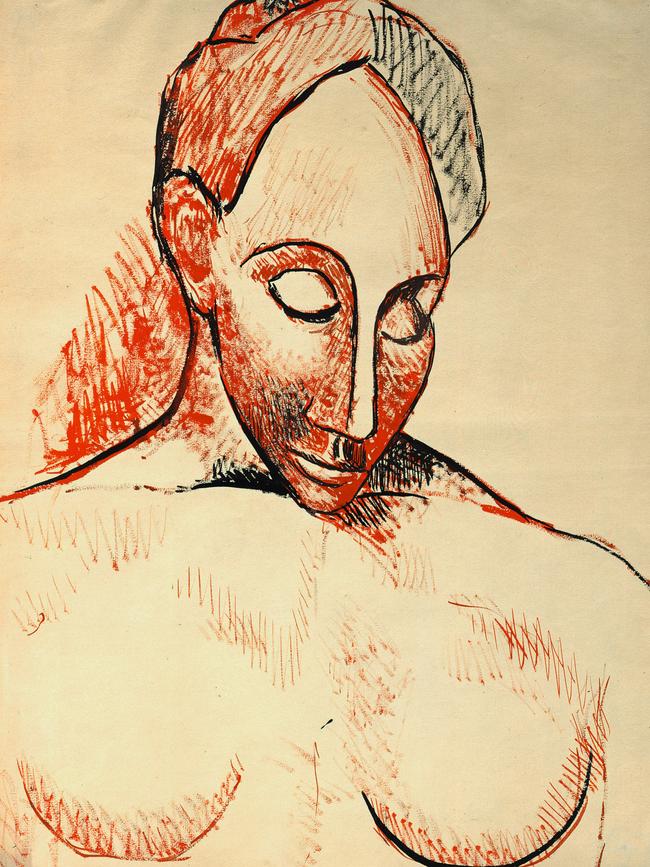

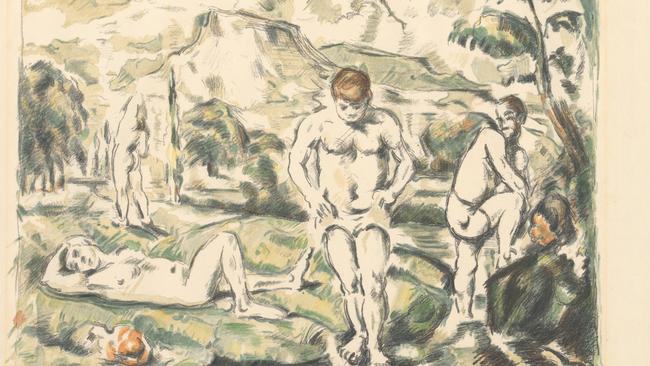

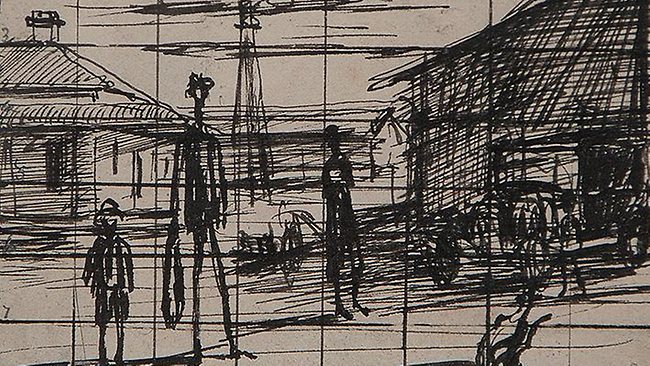

Among the legion of students who attended the school and frequented Nibbi’s bookshop (which included artists such as Fairweather, Eric Thake and Eveline Syme) was Drysdale, who said his “introduction to what we call modern art was Cezanne and the classical attitude”. This foundation is clearly laid out in Drysdale’s Composition 1937, with the sketchy application of pigment, dynamic arrangement and classically derived female forms inspired by Cezanne’s many multi-figured paintings of bathers in undefined arcadias.

Drysdale’s adventurous reworking of modern styles arose as much from formal instruction as it did from his admiration and emulation of the work of fellow students, and he became one of Bell’s most accomplished acolytes.

While Australian artists active between the world wars largely relied on imported reproductions to gain an appreciation of the new visual pathways forged by Cezanne, his paintings were made widely available in Australia for the first time in 1939 – the centenary of his birth – in the Exhibition of French and British contemporary art organised by the Herald newspaper.

Featuring more than 200 works by contemporary artists working across neo and post-impressionism, fauvism, expressionism, cubism and surrealism, the show toured the country and attracted more than 70,000 visitors in all state capitals. It electrified Australia’s cultural circles, ignited debates about the value of contemporary art, and promoted Cezanne as the “grandfather” of all 20th-century artists. The exhibition’s curator, Basil Burdett, declared: “Never before has an artist exerted such a profound influence.”

Indeed, Cezanne’s way of picturing the world through form and colour would be translated and reinterpreted by Australian artists for years to come.

Edited extract from a curatorial essay by Deirdre Cannon, David Greenhalgh and Natalie Zimmer on Cezanne to Giacometti: Highlights from Museum Berggruen/Neue Nationalgalerie, which runs at the National Gallery of Australia from May 31 to September 21. .

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout