As the century progressed, our new understanding of these laws led to further advances in such vital areas as chemistry, and to the practical application of scientific knowledge in what came to be known as the Industrial Revolution. At the same time, however, artists, writers and musicians began to be drawn to the vast areas of human experience, including our experience of nature, that could not be explained by the new science.

Two romantic themes in particular were discussed here last week: one was the idea of natural forms as organic rather than mechanical, and the application of this paradigm to literature in the critical writings of Coleridge, to the design of gardens in theories of the picturesque, to architecture in the rediscovery of gothic, and even, with Herder, to the articulation of the modern anthropological concept of human culture.

Another important romantic theme was that of the sublime — of the grandeur of natural phenomena before which we feel dwarfed and terrified, and yet also uplifted and even exhilarated. This idea too had consequences for our understanding of authors from Homer to Shakespeare, our appreciation of gothic architecture and ancient ruins, and of course for dramatic and wild natural scenery.

Two of the greatest of romantic landscape painters, John Constable and JMW Turner, as suggested last week, can be considered as respectively epitomising those two themes; Constable with his vision of human life as inseparable from the living processes of nature, and Turner with his pursuit of a transcendent sublime that had once dwelt in the background of Claude’s classical compositions, as the ultimate horizon of human life.

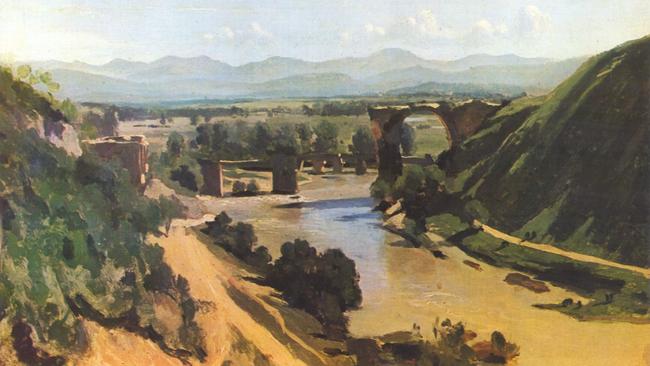

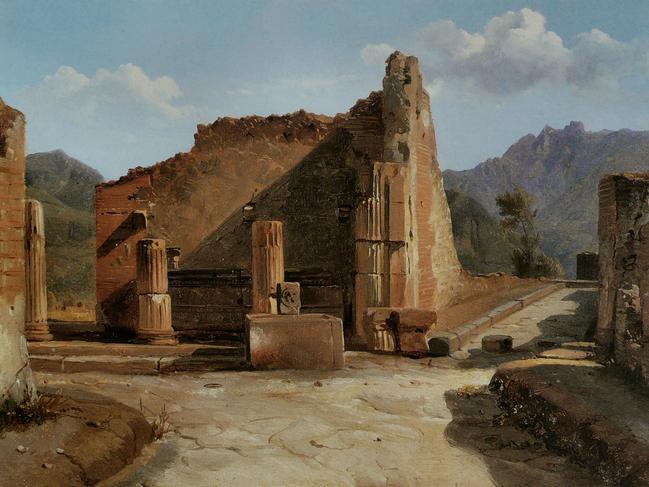

Not all the painters of this period were so overtly concerned with these romantic themes, however. As we saw, the founders of the modern plein-air tradition — that is, specifically the practice of painting oil studies directly from nature — were young neoclassical painters studying and working in Rome.

This did not mean that they were unaffected by romantic ideas, and in fact the distinction between neoclassical and romantic is sometimes artificial and certainly more complicated than is often suggested. At any rate, the young artists in Rome were constantly painting ruins — a favourite romantic subject — surrounded by picturesque vegetation and redolent of the sublimity of time and the frailty of human ambition.

But unlike Caspar David Friedrich, with his spectacles of inhuman natural grandeur, a painter like Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot, one of the most important figures of this period, was mindful both of the history of his subjects and of the painterly tradition within which he worked. And we can almost define the history of landscape in France in the 19th century as an arc that reaches from Corot to Cezanne, framing the period of impressionism, with its distinctive aesthetic concerns.

Corot showed early promise, and was briefly the pupil of a brilliant but short-lived neoclassical painter with a name that evokes both classical and romantic associations: Achille-Etna Michallon (1796-1822).

But it was in Rome (1825-28) that he really found himself, in the process of painting in and around the city. Peter Galassi’s Corot in Italy: open-air painting and the classical landscape tradition (1996) is an outstanding study of his oeuvre and an excellent introduction to the culture of early plein-air painting.

Corot is often lazily spoken of as a precursor of the impressionists, but this is both to misunderstand and to underestimate his achievement. Corot did indeed bring open-air painting back from Rome to France, but he was inevitably conscious of the architectonic structure of landscape, and the heritage of Nicolas Poussin, the single most important figure in the history of French painting.

But Corot was also influenced by a romantic sense of the life of nature, so that he has an acute feeling for the material substance of the things that he paints, whether a rocky bank, a dusty road, water or trees and foliage. He could never have conceived the purely optical ambitions of the impressionists, like Monet who once said that he wished he had been born blind and then regained his sight so that he could paint without knowing what objects corresponded to the patches of light he was seeing.

Even in Corot’s late works, like Ville d’Avray (c. 1867), which are suffused in a dreamy and melancholy moodiness, there is always a combination of classical structure and romantic sentiment, never the optical neutrality and disengagement of impressionist painting. These concerns — with compositional structure and with the meaning of natural motifs — would both return after the interlude of impressionism.

Impressionism is one of the easiest of artistic styles for the uninitiated viewer to enjoy, for it assumes no cultural knowledge, presents no complicated moral narratives to unravel, and confronts us with no difficult social or political questions. And yet the work was briefly controversial when it was first shown, because it seemed to flout contemporary artistic conventions. Today, when it is a cliche that modern art should be unconventional, museum publicists love to play up the allegedly radical nature of impressionist painting while knowing that it really presents no difficulties at all to their audiences.

In all this, what is really interesting about impressionism tends to get lost. It has nothing to do with being politically radical, nor is it just about producing blandly pleasurable pictures for a middle-class audience. What is most important about impressionists’ best work is the quest for a new kind of authenticity in the immediacy of visual experience, in the personal, unique and subjective sensation of a transient moment.

To achieve this, they extended the practice of plein-air painting that had originated with the young neoclassical painters in Rome a century or so earlier. These painters had made studies outdoors and in front of the motif, but had generally completed their exhibition pictures in the studio. The originality of the impressionists was in their attempt to paint finished pictures as much as possible from life and outdoors.

This is much harder than it might seem to the lay person. Even in painting a small oil study from life, the artist encounters many difficulties, not only with heat, cold, wind, rain, passersby, insects, etc, but because the scene before their eyes is constantly changing. Clouds come and go, the sun moves across the sky, the direction of light, its intensity and its temperature are in constant flux.

In Monet’s Le Bassin d’Argenteuil (c. 1872), for example, we have a view of the Seine early on a summer morning. We probably imagine the artist coming out with his painting kit at about six in the morning and being struck by the beautiful freshness of the scene, with its bright light and long shadows stretching across the riverside walkway. But by the time he has set up his easel, the rising sun will have shortened those long shadows; and as it comes up over the trees, the deep shadow on the right will disappear, destroying the whole composition.

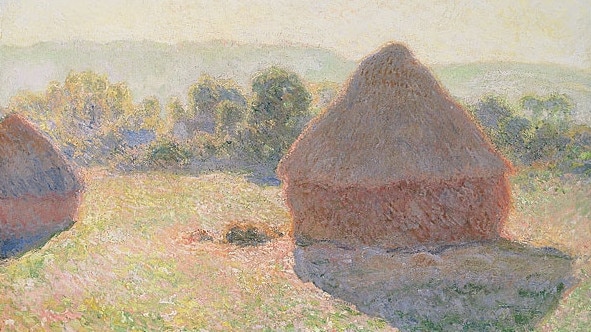

This means that the idea of capturing the spontaneous impression of a transient natural scene is fraught with paradoxes: the artist will in reality have to do much of the painting in conditions that are no longer like those that inspired him initially, and come back the following day if he wants to see those striking long dawn shadows again. This is why Monet ultimately came up with the idea of painting the same motif at distinct times of day, successively and day after day, as he did with the great Haystacks or more properly Grainstack series.

The deeper question is why the impressionists sought authenticity in the subjective, the ephemeral and the transient. All artists are searching for truth of some kind: but why did Claude Lorrain find truth in the perennial, while his later namesake, Claude Monet, pursued it in elusive and changing impressions?

Perhaps one reason lies in the challenge of photography, which was becoming more ambitious in scope by the 1860s and threatened painters with the prospect of mechanically produced images of the world. While the academic artists of the second half of the century sought to outgun photography with grand-scale objective naturalism, impressionism resorted to the subtlety of a subjective, optical naturalism.

But is that all there is to it — that is to say, an explanation founded in competing technologies of representation? Or is there also something more intangible? In the age of burgeoning mass society, whose great and lonely cities full of strangers were evoked by authors as different as Balzac and Baudelaire, authenticity was perhaps only to be found in the assertion of private and intimate experience.

This tendency to focus on the subjective world of individuals is also a fundamental theme in the modern novel, which reaches its apogee in the century or so from about 1830, the date of publication of Stendhal’s Le Rouge et le noir, to the 1930s.

The profoundest depths of the subjective were explored by Proust, who more or less brings this period to a close with Remembrance of things past, the last volume of which appeared posthumously in 1927.

And yet, in painting, the pursuit of optical subjectivity did not satisfy artists for more than a generation at most.

The origins of the impressionist movement were in the 1860s, its first programmatic exhibition was in 1874, after the Franco-Prussian war, and, by the time of its last one in 1886, a younger group of artists as different as Seurat and Gauguin were pulling in very different directions.

Perhaps the most important of these, however, was Cezanne, who had in fact been part of the impressionist group from the beginning, but whose early works were almost deliberately awkward and clumsy.

It was under Pissarro’s influence that he came to a deeper understanding of landscape, and Pissarro had been the pupil of Corot; and so it was that Cezanne came to be the ultimate heir to Poussin’s analytical and architectonic vision of landscape.

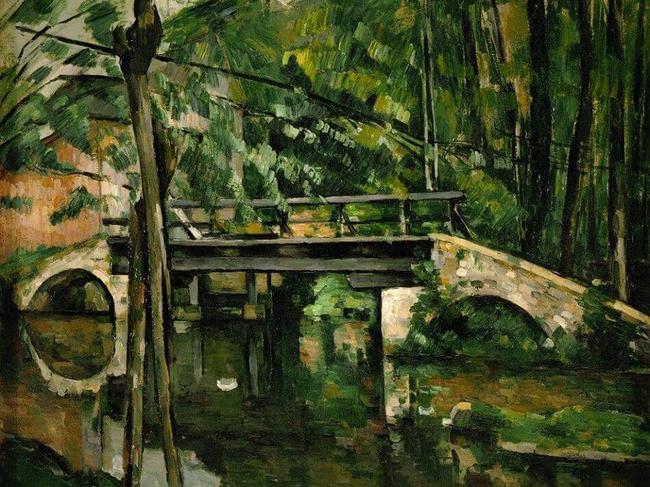

From his earliest compositions, Cezanne is similarly drawn to the virtual grid of horizontals and verticals that echo the artificial matrix of pictorial form. Architecture, bridges and the little cubic buildings that later inspired Braque and Picasso give his compositions structure and invite us to seek the natural lines in the landscape. In the tangible delight in constructive form of a painting like The Bridge at Maincy (1879) we can feel what Cezanne was getting at when he said that he wanted to “do Poussin again, but from nature”.

The romantic landscape, as we saw last week, was inspired by the new sensibility to nature that arose from the mid-18th century onwards. The Enlightenment had been naturally excited by the post-Newtonian sense that the laws of nature had been revealed to human reason: as Alexander Pope wrote, “Nature, and nature’s laws lay hid in night; / God said, let Newton be, and all was light.”