Artist Russell Drysdale helped Australians understand the land

THE drawings of one of our most important painters, Russell Drysdale, are the subject of a substantial exhibition in Sydney.

RUSSELL Drysdale, who was born 100 years ago last month and died in 1981, was undoubtedly one of our most important and influential painters of the post-war years, and particularly of the third quarter of the 20th century.

He was, together with Sidney Nolan and later Arthur Boyd, among the first Australian artists to be taken seriously internationally, which meant principally in England, where Australian art came to be seen as a particularly vital branch of the British tradition. At the same time he defined for Australians too a new way of imagining our experience of living in this land.

How to inhabit the new continent, how to feel at home in a distant and strange environment has been the primary concern of Australian art since settlement, and successive generations have brought different stylistic approaches to the problem, from the picturesque topographical language of John Glover and the rigorously analytical yet romantic vision of Eugene von Guerard to the plein-airism of the Heidelberg painters.

As important as style, however, has been the choice of locations that have been implicitly taken as epitomising the relation of Australians to their environment. The early colonial artists naturally painted the new settlements and land cleared for farming. The generation of von Guerard went farther afield in quest of the sublime subjects that spoke of the spirit of the land itself. The Heidelberg painters moved back from the grandiose to the familiar, and painted natural scenes tamed and made hospitable by human labour.

What had hardly ever been represented was the flat, almost uninhabitable stretches of marginal pasture land that compose so much of the Australian continent, and that verge on the still vaster areas of actual desert. Hans Heysen had painted the Flinders Ranges in the years before World War II but at least the wasteland he represented was given shape by mountains. It was only in the years immediately following the war that Nolan and Drysdale discovered the outback as a subject, a metaphor of Australia.

Nolan's 1946 painting of Ned Kelly riding away into vacant flatness is one of the most memorable images in modern Australian painting, but in fact Drysdale had been the first to evoke life in this harsh environment and was the more consistent in his development of the theme. He had begun with the striking, if still rather mannered, compositions of his early maturity, in which impossibly elongated stick-figures stride through flat country punctuated only by leafless stick-trees, as in Man Feeding His Dogs (1941).

Drysdale's understanding of the land he had already elected as the setting of his compositions was immeasurably deepened by his visit to the drought-stricken outback of western NSW as part of a commission from The Sydney Morning Herald in 1944.

His figures acquire a new volume, expressive of the stoical and almost stolid personality required for survival under these conditions; his sense of space, texture and colour all come to embody a powerful and coherent vision of existence in an environment far from the settled world of Heidelberg.

Throughout Drysdale's development, drawing was a constant resource and a medium for developing ideas and solving problems, and his drawings are the subject of a substantial exhibition at the S.H. Ervin Gallery in Sydney, mounted to mark his anniversary and accompanied by a fine catalogue - or rather a book, since it includes many more images than are in the show - by Lou Klepac, which gives an excellent idea of the range of his graphic work.

Unlike Donald Friend, who was one of Drysdale's close friends, Klepac points out that Drysdale was not an obsessive draughtsman. He did not carry a notebook around with him, driven by a constant need to transcribe experience in graphic terms. Most of his drawings are made to serve a purpose, initially as part of his training as an artist, then in a variety of roles connected with the conception of his pictures, from devising the attitudes of figures to determining spatial composition and its layout on the two-dimensional surface of the picture plane.

The least satisfactory pictures, in fact - though perhaps the most superficially attractive to many viewers - are those that stand on their own as finished portraits of outback characters. There is something rather too anecdotal, illustrative and even sentimental about these drawings, compared with the open-ended quality of the working sketches and compositional studies, which appear in a fascinating variety of media, from pencil or charcoal to ink and wash.

From very early on, however, we can observe a preference for pen and ink, media that are responsive to movement and organic life, and that are better suited to working from memory - a practice encouraged by Drysdale's teacher George Bell - than to precise definition of volume and space. Both the strengths and the limitations of Drysdale's process can be appreciated in the drought drawings, where we can feel him seeking the characteristic silhouettes and, as it were, gestures of the desiccated tree trunks in the desert.

On one sheet in particular (c1944) he has three rows of such forms, presumably invented on the basis of trees actually observed, and now distilled almost into ideograms. The forms are inventive and eloquent, but they are conceived as silhouettes rather than in three dimensions, and this weakness in the grasp of solid form is apparent in a small painted study (1945) in which the trunks lying on the ground are surprisingly flat and lacking in substance.

Drysdale compensates for this lack of volumetric drawing by resorting to surface texture, as we can see in several other studies of this period, both in black and white and in colour. The approach is particularly successful in other wartime subjects, such as the dramatically effective nocturne of Albury station and the striking images of the air base at Rose Bay, with its surreal assemblages of broken aircraft wings piled up like gigantic still-lifes outside hangars, the whole thing held together by a dramatic use of colour and the livid glare of artificial light.

Here and throughout his work - as in the little Kimberley Landscape (1961) - we can see the simultaneous instinct for capturing the vital forms and movements of plant and even mineral forms, and the transformation or translation of all this into a product of artifice, deliberately composed and executed in a conscious and decisive choice of colours that originate in nature itself but become, in Drysdale's hands and in his particular selections and juxtapositions, quintessentially expressive of the outback.

The linear and gestural emphasis of his pen-and-ink drawing is particularly apparent in his studies of human figures, from the more solid and documentary drawings of soldiers - in one case a fine sketch of several figures in an operating theatre - to the more summary linear notations for one of his most memorable mature paintings, The Rabbiters (1947). Whether rapid and gestural or more fully worked out, however, all these drawings emphasise the characteristic movements and attitudes that Drysdale seeks in all his paintings, whether motion is overt and actual, as in Man Feeding His Dogs or apparently frozen in Shopping Day (1953), which is included in the exhibition.

The impression of movement arrested and potential rather than absent is characteristic of the later work. With this comes a new concern for monumentality, and it is not surprising to discover that a study for The Drover's Wife (1945) is executed in pencil, for the concern in this case is precisely to endow the figure with volume and mass, rather than with outwardly visible animation.

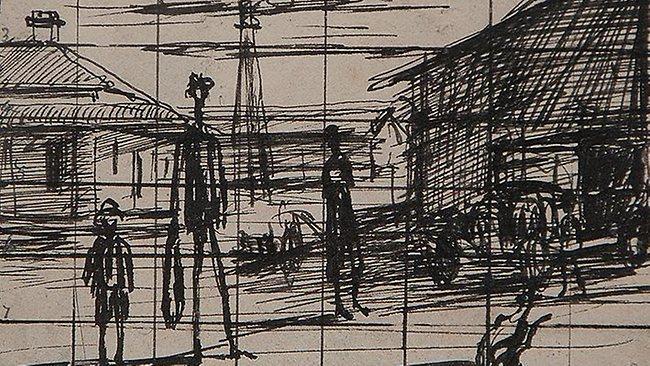

Among the most interesting drawings are the compositional studies that, not surprisingly, were often executed in pencil, because in this case the priority is not spontaneity but planning. These drawings are carefully thought out, constructed with the use of a grid, in many cases dividing the composition into eighths in both directions, ascribing numbers to the horizontal columns and letters to the vertical ones. Sometimes the diagonals are marked as well, and not only the diagonals of the whole rectangle but all the other parallel diagonals as well in both directions.

The division into eighths has a particular point, apart from the obvious fact it is the next subdivision of quarters: the division of any line at the 3/8 point gives an approximation to the golden section, which is strictly 1:1.618 but in practice near enough to 3:5 and 5:8 - the golden section being the unique point at which any line can be divided in such a way that the ratio of the short dimension to the long is the same as that of the long to the whole.

The results can be seen in many of the drawings, emphasising that these grids are indeed for compositional purposes and not simply as a tool for squaring up to a larger scale. In the tiny ink Study for Going to the Pictures (1941), for example, the top of the roofline on the left is at 3/8 from the top of the picture, while the edge of the barn on the right is at 3/8 from the right side. Such devices, very common in the work of Jeffrey Smart as well, help to anchor the composition in a necessary relation to the inherent geometry of the picture plane.

The later Study for Hill End (1948), drawn in pencil, is even more detailed, although the geometrical effects are somewhat less obvious. On the left the lower roofline almost corresponds with the 3/8 division from the top; if these lines do not match exactly, it is perhaps for the same reason that Cezanne, while emphasising verticals and horizontals in his compositions, avoids any that are too exactly straight, and thus creates a kind of tension between ideal geometry and the forms of the natural world.

On the right, the footpath follows the line of the diagonal of the second rectangle from the bottom. If the little human figure, meanwhile, appears isolated, it is because every rectangle is a square and a supplement; the square can be drawn from either end, but in this case it is most logically on the left, encompassing the whole building but leaving the man conspicuously outside.

Much more could be said about these drawings, especially in relation to the finished paintings, but there is no doubt that we repeatedly encounter here what the artist himself called "the germ of an idea", which may evolve or be discarded in the finished painting: in this case the rather awkward and tentative little man in the study has disappeared altogether in the finished painting in Geelong, giving way to empty space and evoking, instead of the human presence a house should suggest, the melancholy of a ghost town.

Russell Drysdale: The Drawings

S. H. Ervin Gallery, Sydney, to March 25