The queen of beauty

Botticelli, that resonant hero of the Renaissance, was not always revered, writes Christopher Allen

Botticelli. Botticelli Staedel Museum, Frankfurt, Germany. Until February 28.

FRANKFURT is often rather unfairly considered as little more than a transport hub for central Europe, when in fact the city has a long and distinguished history - it was unfortunately severely damaged during the war - and an important art collection, a selection of which, from the 19th and 20th-century holdings, will be travelling to Australia for an exhibition in the Melbourne Winter Masterpieces series in June.

At the moment, though, the Staedel Gallery has an important show of the work of Sandro Botticelli (c. 1445-1510), who ran one of the principal workshops in Florence in the third quarter of the 15th century. In contrast to his main rivals, Ghirlandaio (the master of Michelangelo) and Verrocchio (master of Leonardo da Vinci), Botticelli, as the crowds of visitors filling the exhibition space attest, is today one of the most resonant names of the Renaissance.

It was not always thus. As Vasari's biography records, the artist outlived his fame and passed the last years of his life in sad oblivion, a shadowy figure limping around Florence. The trouble was that his style was not deeply grounded in the mainstream of Renaissance concerns, and his later religiosity exacerbated its old-fashioned appearance in the eyes of contemporaries.

As the canon of modern masters was formed in the course of the 16th century, Botticelli was omitted from the list. For Vasari, he was part of the so-called second manner of Renaissance art, left behind by the consummation of the terza maniera in what we call the High Renaissance. For later centuries, he was counted among the Italian primitives, the artists of the 14th and 15th centuries who preceded Leonardo.

It was not until the 19th century, and especially in England, that the Italian primitives were rediscovered, their revaluation corresponding to a depreciation of much of what we now call mannerist and baroque art. Ruskin, the most influential critic of the century, wrote about Botticelli as well as other early Italian painters, but even more important, arguably, was Walter Pater, the Oxford academic and classicist.

Pater's collection of essays, The Renaissance (1873), is often underestimated by art historians, no doubt because it is a work of criticism rather than of history. But it has certainly had an incalculable importance in forming modern attitudes to the renaissance, and in that sense it has actually made history.

If the person in the street today has any idea at all about Giorgione, Botticelli or Leonardo, it is largely because of Pater's essays on these artists; the Mona Lisa, previously unknown to the general public, owes its status as the most famous painting in the world to Pater's eloquent, if at times slightly purple, prose ("older than the rocks among which she sits").

Botticelli's particular poetic quality was epitomised by a type of female beauty that became a frequent reference in modern literature; the idea of a Botticelli beauty appears memorably in Proust's Remembrance of Things Past, where Charles Swann, who is normally attracted to robust working-class girls, is caught off guard by the subtle and melancholy beauty of Odette, with whom he falls desperately in love.

This image of beauty is at the heart of the Staedel exhibition, and it illuminates the first half of the show in particular, by virtue of tracing the ideal back to something like its point of origin in the real world.

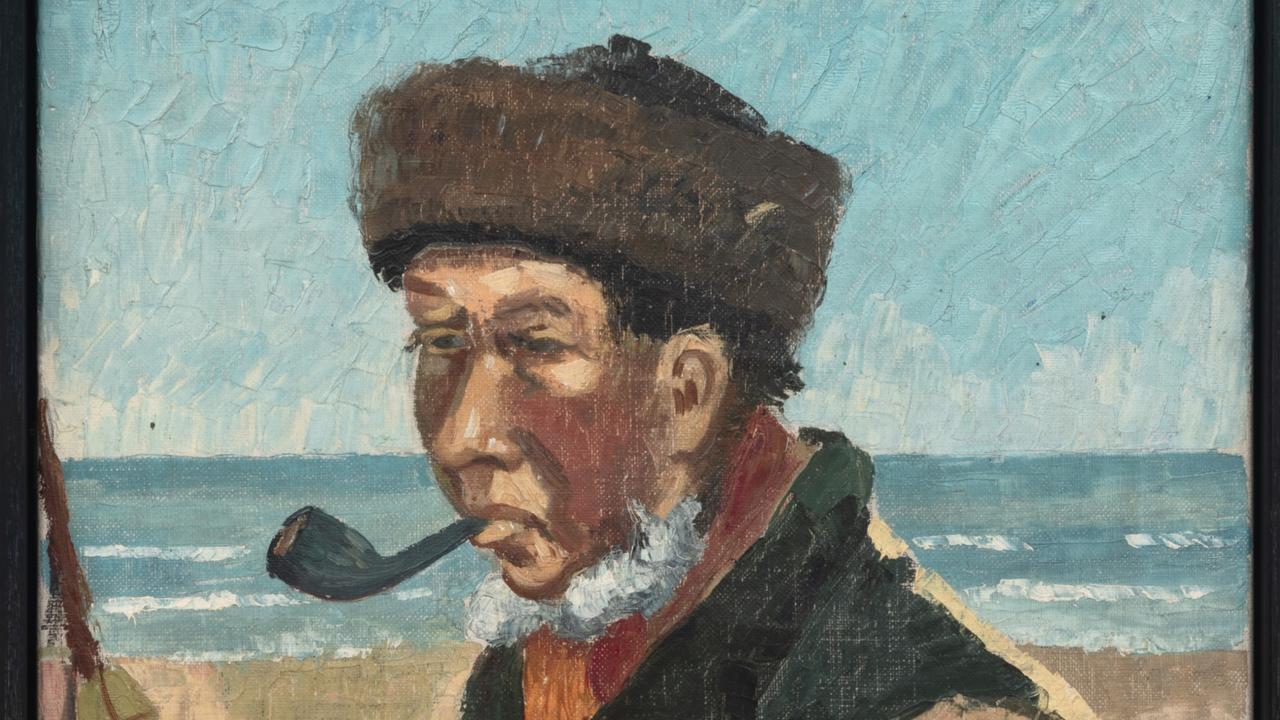

The exhibition begins with an unusually large and impressive profile portrait of a beautiful girl, set against a black ground, a masterpiece that belongs to the Staedel Museum. She has always been identified with Simonetta Vespucci (1453-76), a young woman considered the most beautiful in Florence, and the mistress of Lorenzo the Magnificent's younger brother Giuliano.

But if this picture is something like the epicentre of the whole exhibition, it is not simply because of the charm of la bella Simonetta. It also needs to be understood in relation both to the history and the philosophy of contemporary Florence.

The city was a proud republic, while others in Italy were principalities or tyrannies, or governed by the ecclesiastical monarchy of the pope. But unlike the much more formally structured republic of Venice, Florence had come under the sway of a rich and powerful family, the Medici. By the later quattrocento, Lorenzo the Magnificent conducted himself like a princely ruler.

He had a court, encouraging artists, writers and intellectuals who worked under his direct patronage. Like his grandfather Cosimo the Elder, he encouraged neoplatonism, a philosophy that among other things offered a way of reconciling Christian teaching with renaissance pleasure in this world; the themes of beauty and love were at the core of neoplatonic thinking.

Renaissance courts also played with the already archaic but still romantic pageantry of medieval chivalry, whose tradition of courtly love could be assimilated to the neoplatonic conception of ideal love. It was in a joust in 1475 that Giuliano chose Simonetta, in accordance with chivalric tradition, as his lady, calling her the queen of beauty. The following year, the young woman died, apparently of tuberculosis, and we might hardly have heard of her again but for the events of two years later.

In 1478, the Pazzi family was involved in a plot to murder Lorenzo and Giuliano, and overthrow Medici power. Giuliano was killed, but Lorenzo escaped, rounded up the conspirators and had them executed.

As the Pazzi conspiracy was instigated by the papacy in Rome, Lorenzo celebrated Giuliano as a martyr to Florentine independence. The exhibition includes the portrait of Giuliano from the National Gallery in Washington, showing the man with downcast eyes and an open doorway behind him.

The portrait may be posthumous, unless the dove refers to his mourning for Simonetta. The doorway is a symbol of death going back to antiquity, where Mercury, in his role as psychopompos, or guide of souls into the next world, is often seen standing half-concealed by an open door. Giuliano himself is identified with Mercury in Botticelli's Primavera, where the god is given what appears to be an idealised version of the features in this portrait.

This association is of special interest, because the neoplatonists in Florence attached great importance to a collection of late antique philosophical and occultist writings known as the Corpus hermeticum, which they wrongly thought to be of immense antiquity and ultimately deriving from Hermes or Mercury in the form of Hermes Trismegistus.

Simonetta, precisely because of the importance of love in neoplatonic philosophy, was taken as Giuliano's mystical consort and underwent a kind of apotheosis for which the paradigm was, of course, Dante's transformation of Beatrice Portinari in The Divine Comedy.

The Staedel portrait of Simonetta is also posthumous, as is proved by the cameo she wears around her neck, which reproduces a medal struck by Lorenzo to commemorate the defeat of the conspiracy. The medal and cameo represent Apollo victorious over the satyr Marsyas, a familiar theme in neoplatonic philosophy. Around the neck of a young woman, the myth could evoke the victory of reason over baser drives.

Both of these themes are brought together in the greatest mythological painting in the exhibition, the Minerva and the Centaur lent by the Uffizi. Minerva appears with the features of Simonetta, as she had on the jousting banner painted by Botticelli for Giuliano (some idea of the original is given by a later tapestry, also in the exhibition).

Centaurs are generally symbolic of ungovernable passions, and the composition ostensibly shows the goddess of reason effortlessly subduing the intemperate beast by taking a lock of his hair between her fingers. But the Medici emblem of three interlocking diamond rings, repeated over the goddess robe, means that she also evokes the wisdom of Medici statecraft overcoming lawless violence in the city.

Botticelli fully concurred with this apotheosis of Simonetta; he is said to have been in love with her himself, and was eventually buried, at his request, at the foot of her tomb. At any rate, her features, in idealised form, recur in the Graces (but not Venus) in the Primavera, and in the goddess herself in the Birth of Venus.

Neither of these great paintings can be lent, unfortunately, but the figure of Venus from the latter work is reproduced without its context in two studio copies that are included in the exhibition. Only in the rarefied philosophy of neoplatonism, incidentally, could the images of the virginal Minerva and the highly sexual Venus be brought into such close proximity.

It is because the figure of the Virgin Mary is also an embodiment of love and even a kind of ecclesiastical version of the ideal lady of courtly love that the second half of the exhibition, which deals with religious imagery, does not feel quite as disconnected from the first half as it might.

Mary is the focus of several beautiful works, perhaps most exquisitely in the Wemyss Madonna, where the light blue and pink of her robes harmonise, respectively, with the sky and with the mass of roses that fills the left side of the composition. Again we recognise a version of the features Botticelli seems to have derived from Simonetta.

The serenity of these works was banished, at the end of the 15th century, by the influence of Savonarola, a preacher who inveighed against pleasure and moral corruption. The extent of Botticelli's involvement with the Dominican has been questioned, but there is no doubt about the change in his style.

The great Munich Pieta, unfortunately not in the exhibition, still embodies a kind of equilibrium between humanism, in the grace of the youthful, beardless Christ, and the strangely leaning, angular saints who crowd anachronistically as in a sacra conversazione.

Among the works that epitomise the late style, the exhibition includes, for the first time, all four panels of the story of Saint Zenobius, one of the patrons of Florence. In their crabbed, anguished figures, crowded yet moving around in a space they cannot occupy, these compositions make one think of someone wearing an oversized overcoat.

There is none of the harmony between the volume of figures and the space in which they are set which we associate with the High Renaissance. But this simply reminds us that Botticelli had never been interested in the mainstream modern concern with mass, volume and space.

His figures have the calligraphic elegance of the international gothic style of almost a century earlier, while the flat space of the Primavera, filled with flowers and trees, recalls, as has so often been said, the richly patterned background of a tapestry.

What made Botticelli a great artist of the Renaissance was not a new sense of the material reality of the world, as for Masaccio, but the idea of beauty and the poetic and mythic images that he assimilated from the neoplatonic humanist environment in which he moved. When that delicate world of poetry and dreams was mowed down, he was left marooned in late medieval angst.