Seeing was believing in the early days of Australia's white settlement

SYDNEY, Melbourne and Australia's unique fauna are the focus of two exhibitions exploring the early days of white settlement.

THIS is, unusually, an exhibition in two parts, divided between two sites and with different opening and closing dates.

These eccentricities aside, it represents an outstanding collection of images of the early days of white settlement, including many recent acquisitions and bequests, and some works presented for the first time.

The first part of the exhibition, at NGV International, is devoted to early images of Australia, with a natural bias towards Sydney as the original colony, while the second section at Federation Square, somewhat smaller, focuses on Melbourne and a correspondingly later historical period.

The first part plunges us back into a strangeness of the new land at the ends of the earth with its unfamiliar landscape and bizarre fauna that must have provoked uneasy reflections on the biblical narrative of creation (did Adam name the kangaroo and the koala too?).

It was not a matter of a few new specimens to be added to the corpus of existing botany and zoology, but a whole new world of plants and creatures.

The sense of oddness is often compounded by the naive style of early amateur artists and even sometimes by unforeseen semantic shifts; thus an emu is labelled on an anonymous print of 1792, "A non descript Bird found at Botany Bay", where the author means to say that it has not been previously described, adding that the print is "from a drawing made on the spot", the first of many such assurances, designed to forestall the reader's incredulity.

The most famous case of a creature too strange to be believed was the platypus: a furry creature with a duck's bill was naturally suspected of being a hoax, particularly when one remembers there was a long history, since the 16th or 17th centuries, of hoax sea-monsters and fake mermaids, manufactured by idle sailors anticipating the telling of tall tales when they got home.

Even our less extravagant creatures, such as the kangaroo, were peculiar enough. Cook brought back a skin from his first voyage to Australia (1768-71), had it stuffed in London and then painted by the greatest animal painter of the time, George Stubbs (1773). The animal's body faces left in the original painting, while its head turns to the right; this attitude is reversed in the engraving that accompanied the 1773 publication of the voyage, although not in some later prints.

Another creature depicted from a stuffed specimen, but with less skill and imagination, was the possum illustrated in the account of Cook's third voyage, published in 1784.

An Opossum of Van Diemen's Land, based on drawings by John Webber, stands stiffly like a child's toy, with a vacant glass eye and a gaze as fixed as its jaw; this image and that of the kangaroo are copied as wood engravings in Thomas Bewick's General History of Quadrupeds (1790), which also includes the first illustration of a possum made from a living specimen "in the possession of the reverend Mr Egerton, prebendary of Durham".

By 1791, a living kangaroo, "the wonderful kangaroo from Botany Bay", was on display in the Haymarket area of London, and by 1792 a pair were living in the Royal Gardens at Richmond.

Soon afterwards, many Australian animals were to be seen in Paris, as the Nicolas Baudin expedition sent out by Napoleon in 1800 arrived home with no fewer than 73 living animals among a scientific haul of 200,000 or so specimens from Australia and other countries.

Prints from that voyage, based on drawings made by Nicolas-Martin Petit and Charles-Alexandre Lesueur in collaboration with Francois Peron, the zoologist who later published the account of the expedition after Baudin's early death in 1803, are among the new NGV acquisitions in the exhibition, and are outstanding evidence of the generous and enquiring spirit of the Enlightenment.

They include a circular frontispiece in which we see black swans and kangaroos in the Empress Josephine's gardens at Malmaison, as well as many beautifully illustrated plates devoted to a wide variety of creatures, from large animals to tiny marine life forms.

The new zoological universe of Australia extended far beyond the handful of picturesque marsupials that were becoming well known around the world.

Three plates, for example, are devoted to marine invertebrates, including jellyfish and sea-anemones; in one we find the first illustration of the bluebottle, bane of Sydney summers at the beach.

The same precise attention to detail and sensitivity to morphology is brought to the depiction of the tools and weapons of the Aborigines, including spears, harpoons, fish-hooks of seashell and casse-tetes de differentes formes - clubs (literally head-breakers) of various shapes.

Images of the Aborigines themselves were executed by Petit, invariably in a spirit of sympathy, and usually named rather than considered as generic types; in fact it is important to reflect that although these images are ethnographic in intent, they were also made at a time imbued with a strong sense of individualism, and that is reflected in the particular character of each sitter.

The curiosity of the French scientists extended to Aboriginal songs and there is a sheet of notated chants, including the cry "coo-ee".

A genuine interest in the Aborigines is characteristic of most early representations of them. The hand-coloured aquatints made after drawings by John Heaviside Clark, published under the rather quaint title Field sports of the Native inhabitants of NSW in 1813, are actually informed by close observation of their practices in hunting animals, although Clark may have been working from sketches made by an unknown artist.

Some of the hunting techniques and equipment are apparently very accurate, although the figures are somewhat idealised. The kangaroos speared in one scene are the work of an artist who has never seen a living one.

On the other hand the scene of spear-fishing from a bark canoe not only shows how it was done, but reveals how the Aborigines were able to carry fire in these craft, as had been noted in earlier images, in a hollow made in a pile of earth carried at one end.

Charles Rodius' portraits (1834) - lithographs with an inscription assuring us they were drawn from life directly on to the stone - are also sympathetic, and are named portraits, even though they were contemporary, as we are reminded, with the "most sustained conflict" between the natives and the settlers.

Over a generation later, in contrast, S.T. Gill's watercolour The Avengers (c1871) is a chilling image of three armed settlers creeping up on a group of Aborigines camped around a fire under the light of the full moon, evidently intent on revenge for some theft or killing that is left to our imagination.

Oddly enough, Gill, who is not generally unsympathetic to Aborigines, was also capable of painting, almost simultaneously, a Corroboree at night that seems to express nostalgia for a vanished way of life. These ceremonies were often performed with Europeans present, or even for a European audience, from the time of governor Macquarie onwards, but were banned by the Aboriginal Protection Board in the 1870s.

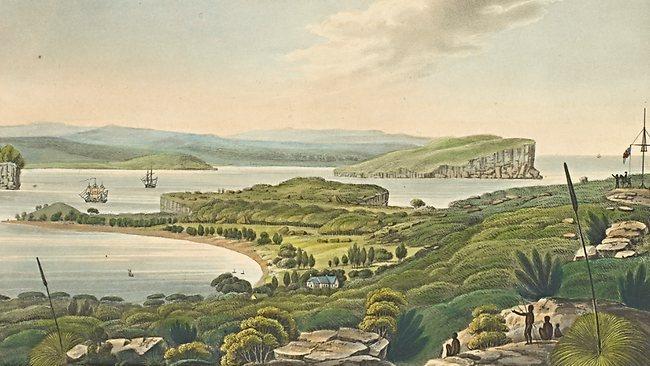

Many of the other images in the exhibition are views of the land either around the original colony or further afield. There are both well-known views of Sydney, like those published by Joseph Lycett, and less familiar images by Walter Preston, who etched the first plates printed in Australia.

The early images document the growth of the colony and demonstrate its flourishing state to readers both here and in England; by the time of Conrad Martens, the concern is more with the picturesque qualities of Sydney harbour and the Australian bush, but always composed around the reassuring presence of one of the grand Georgian or early Victorian houses that once occupied stately properties and are today, when not demolished, surrounded by the proliferation of the inner city.

If these earlier artists cling to the reassuring familiarity of the growing colony, Von Guerard and others of his generation venture into the wilderness in search of the sublime heart of the new land. But even when Von Guerard draws or paints the less wild subjects of large rural properties and views in their vicinity, the change of spatial sensibility is striking.

He doesn't need Martens' reassuring closure, but is happy to let his views open out into vast perspectives, confident that his fine, detailed rendering can deal with the endless detail and the emptiness, without succumbing to a visual agoraphobia.

Just as inescapable is the change of spatial sensibility with Louis Buvelot, who works closer to the motif, who likes looking into the tangle of a copse or wood, and who seems particularly attracted to paths that disappear into the trees.

Instead of Von Guerard's opening out, there is a sense of closing in, and the fundamentally different sensibility is equally apparent in their handling of drawing materials. Von Guerard articulates his world in a minute precision of fine pencil, ink and wash, which is time-consuming and painstaking, and yet ends up feeling timeless.

Buvelot, on the other hand, works fast and energetically with a broad pencil; he emphasises light and shade, the sense of moment and the mood of particular places.

The second part of the exhibition, which concentrates on Melbourne and some of the important families of the city's early days, includes beautiful portraits by Georgiana McCrae, whose well-to-do family unfortunately forbade her to practise as a professional portrait painter.

But we also naturally encounter Von Guerard and Buvelot again: there is an impressive series of landscape drawings commissioned from the former by a young colonist who had grown wealthy in Victoria and was about to return home (as well as another series of views of his property commissioned from Edward La Trobe Bateman), and there are two large and fine drawings by Buvelot.

The contrast between Von Guerard's scientifically objective vision and Buvelot's more intimate and subjective approach to his subjects must have been as apparent to their contemporaries as to us.

A label accompanying two small landscape paintings by Buvelot has a very telling quote from a contemporary critic as early as 1866: "It really is a comfort and a pleasure to come to [Buvelot's works], they are so sunny, so pleasant, in a word, so nice . . . No mountain, no gum forests, no wilderness, but snug little nooks . . ."

The change in colonial taste noted in my earlier review of the Von Guerard exhibition is here consciously articulated.

This Wondrous Land

NGV International until October 2

NGV Ian Potter until November 27