Why the art world is obsessed with Saint Francis of Assisi

The beloved holy man has inspired art and imagery from the day he died almost 800 years ago to the present.

Saint Francis of Assisi

National Gallery London, until July 30

Arthur Boyd, Saint Francis Tapestries David Roche Collection to September 2

We are accustomed to the idea that much of the art of the renaissance and baroque periods was commissioned by or for religious institutions, but it is a mistake to think of “the Church” as a monolithic structure. It is true that, as heir to the administrative culture of ancient Rome, the Christian Church is uniquely hierarchical and centralised among world religions; but in spite of the primacy of the papacy, it has always remained a collection of related and sometimes rival entities.

Apart from the secular clergy, serving their parishes and answerable to bishops, there are monks and nuns who live a life of spiritual retreat under the leadership of abbots; these communities, emerging from the original system of Saint Benedict and dominating the cultural life of Europe for centuries after the fall of Rome, multiplied and diverged during the course of the Middle Ages. Many other clerical groups arose in subsequent centuries, most recently the Jesuit order of priests, founded in the 16th century and bypassing the secular hierarchy to report directly to the pope – who currently, and for the first time in history, is himself a Jesuit.

Two important new orders arose in the 13th century: the Franciscans and Dominicans, who are friars, not monks, living in convents but active in civil society, rather than retreating to the enclosed and often remote environment of a monastery. These orders became enormously successful in the late Middle Ages and early renaissance, building enormous churches to preach to huge congregations, still among the biggest and most significant in most Italian cities, like the Franciscan Santa Croce and the Dominican Santa Maria Novella in Florence, or the Franciscan Frari and the Dominican San Zanipolo in Venice.

The Dominicans were founded by the Castilian Saint Dominic and the most distinguished member of the order, the Italian Saint Thomas Aquinas, was the pre-eminent philosopher of the medieval Scholastic tradition; his Christian Aristotelian synthesis is indeed still the basis of Christian philosophy and theology today. The Catholic Archbishop of Sydney, Anthony Fisher, O.P., is a member of the Dominican order, officially the Order of Preachers (Ordo Praedicatorum), hence the abbreviation that follows his name, like S.J. (Societas Jesu) for Jesuits.

The Dominicans were the most intellectual order in the Church until the rise of the Jesuits 400 years later, but the Franciscans emphasised heart over mind, reflecting the nature and inspiration of their founder, Saint Francis of Assisi, who has long been the most beloved of saints for the simplicity and sincerity of his life, for his devotion to the care of the poorest and most humble, and for his special affinity with animals and all living things. These were the qualities that inspired Pope Francis to adopt this reign name for the first time, and which led him to declare Francis patron saint of the natural environment and of the ecological movement.

Francis (c. 1181-1226), who died just under 800 years ago and was canonised less than two years later, was born the son of a wealthy merchant and initially enjoyed the life of a young man of his class. But when still quite young, he had a spiritual awakening – somewhat like that of Buddha when he discovered the reality of human suffering – and rejected his father and all material wealth. In a famous story, often represented in painting, he stripped off all his clothes in the middle of the street but the bishop covered his nakedness by enfolding him in his mantle.

Francis is usually seen wearing what became the Franciscan habit, a brown woollen robe tied at the waist with a simple rope, with three knots symbolising the vows of poverty, chastity and obedience, and sandals instead of shoes. He lived alone at first, then was joined by a few followers, and eventually received papal approbation for a new order in 1209, after Pope Innocent III had a dream in which he saw Francis holding up the collapsing edifice of the Church. Subsequently he visited Egypt to preach to the Sultan, and established enough of an understanding to allow the Franciscan order to manage the Christian sacred sites in the Holy Land from that time on.

All of these stories are frequently represented in art – many readers will have seen the beautiful Saint Francis cycle by Giotto in Santa Croce in Florence – as are examples of his unique relationship with the natural world: preaching to the birds, reaching an agreement with the wolf of Gubbio, or singing in praise of the rising sun. The most celebrated of all episodes in his life, however, is the mystical receiving of Christ’s stigmata, which is said to have occurred about 800 years ago and preceded his death by a couple of years.

The National Gallery in London currently has what appears to be a beautiful exhibition – judging from its catalogue – devoted to Saint Francis and the art he has inspired from almost immediately after his death to the present day. The exhibition presents a collection of outstanding altarpieces and paintings in oil on canvas, but the survey of a common subject over such a long period of time is also an opportunity to consider how spiritual experience, and the aesthetic response to pictures, have evolved over the same centuries.

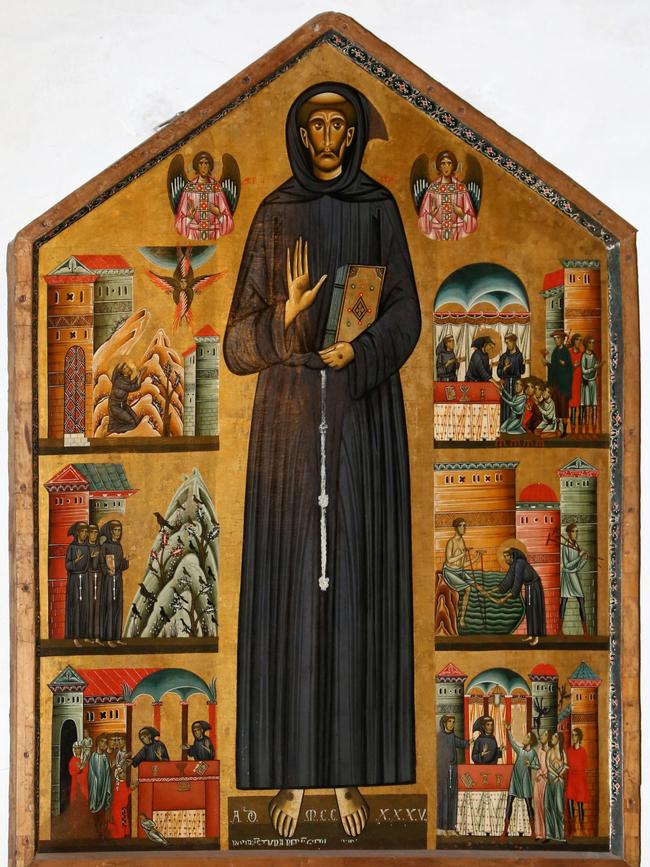

The early altarpieces from the 13th and 14th centuries tend to represent the full-length standing figure of the saint in the centre of the panel, surrounded on both sides by a series of vignettes recalling the famous episodes of his life, like those I have already mentioned.

Bonaventura Berlinghieri’s altarpiece, as early as 1235, is perhaps the best example, with an austere figure of the saint surrounded by six episodes from his legend, including preaching to the birds and receiving the stigmata. This work is illustrated in the catalogue but not included in the exhibition, although the type is represented by two other slightly later and lesser but nonetheless fine works.

The episodic approach is still found in the following century in Siena, where a unique and charming style evolved from the combination of certain aspects of the new renaissance manner of Florence with a deliberately old-fashioned International Gothic elegance and suavity. Two of the outstanding painters of this manner represented here are Giovanni di Paolo and Sassetta, whose beautiful San Sepolcro Altarpiece, made for the church of San Francesco in Borgo San Sepolcro was one of the most beautiful and elaborate of the Quattrocento; unfortunately the complex altarpiece, with some 60 painted panels, was dismantled during the 16th century and sold off after the suppression of the Franciscan convent in 1808-10. Today the National Gallery in London owns seven of the eight principal scenes of the legend of the saint, including his renunciation of worldly goods, his mystic marriage to Lady Poverty and his offer to walk through fire in front of the Sultan.

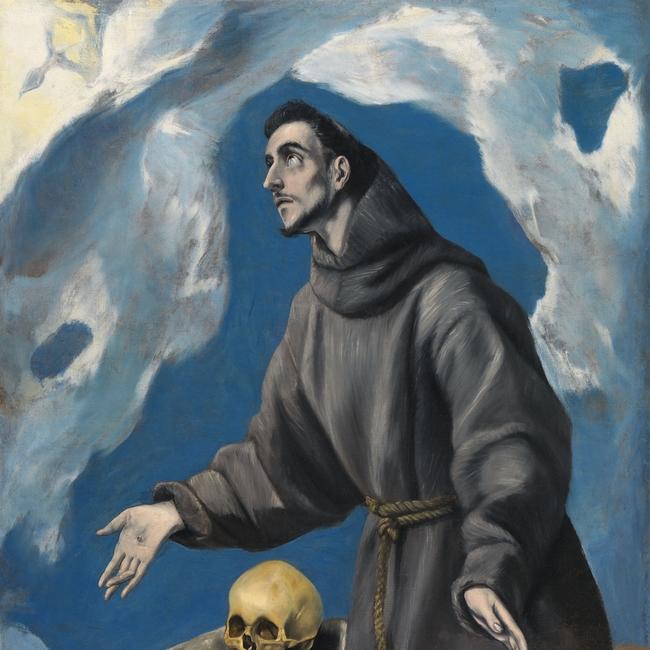

In contrast to this episodic approach, later renaissance and baroque painters, especially from the time of the Counter-Reformation, tend to select a single scene and draw the viewer in to its drama or pathos, as we see for instance in El Greco’s Saint Francis receiving the Stigmata.

In the earlier type of image, we may imagine the small vignettes being used, perhaps by a preacher, as mnemonics to help a congregation visualise and then recall a sacred story. The later focus on a single image and deliberation dramatisation reflect both a more individual, unmediated or solitary relationship between viewer and image, and also the need for a greater effort to evoke a reaction of piety, perhaps in a less spontaneously believing age.

We can ponder similar questions with regard to images of the saint in more recent times, none of which, perhaps, are more striking than the series that Arthur Boyd executed after a visit to Assisi in 1964. While there, he made preliminary sketches of some stories from the corpus of Franciscan legends, and on his return to England he worked these up into pastel sketches, intended as illustrations to a life of the saint by his friend T.S.R. Boase.

In the end, when colour reproduction turned out to be too expensive, he remade the images as black and white lithographs.

A selection of these lithographs is included in the London exhibition, and coincidentally a dozen of the 21, together with the original pastels and their slightly later reproduction as sumptuous large-scale tapestries woven in Portugal, are being shown at the David Roche House Museum in Adelaide – whose remarkable collection of neoclassical art and furniture is well worth a visit in its own right.

Boyd’s Saint Francis images were made some years after the Half-Caste Bride series and just before the Nebuchadnezzar paintings, although they are stylistically closer to the latter than the former, particularly in the dissolution of forms, which suits the mystical and visionary nature of the subject. Boyd, as an intensely emotional man rather than a thinker or intellectual, clearly felt a profound affinity with Francis, even if he did not share conventional religious beliefs.

We can see too that he found in Francis’s life echoes of the recurrent, if not obsessive themes of his earlier work – love, sex, a tormented relationship with his father, a feeling for animals – in the stories of the saint. His choice of episodes only partially overlaps with those that had become canonical in earlier iconography, although they are drawn from some original sources. Thus he has the saint tending to a leper, and a couple of unconventional scenes with the wolf of Gubbio, but also the saint being beaten by his father, lying on hot coals when tempted by a harlot, and preaching naked with Brother Leo.

Boyd faced something like the problem of the baroque artists, but in far more serious form, since both for himself and his viewers he had to make real and vivid the kind of stories and spiritual experience which had become remote from their daily lives and consciousness.

This is one reason why the images he chooses are so violent, corporeal and extreme, compared to the serenity and lucidity of Sassetta’s account of the legend. He has to make the stories brutal and urgent to break through the barriers of modern spiritual obtuseness.

But at the same time, he wants the figures to be spiritual and immaterial, almost like visions, and he achieves this by making the saint’s body a shimmering, boundless form of light.

The lithographic medium brings back a certain linearity and boundedness, but the pastel medium is ideally suited to evoking ineffable luminosity, and thanks to the skill of the weavers, that effect is largely conserved, if somewhat dramatised, in the translation into tapestry, from the opulent chromatic richness of youthful episodes to the transformation of the saint’s body into a mystical effulgence in the ecstatic scene of his naked predication.

Saint Francis of Assisi

National Gallery London, until July 30

Arthur Boyd, Saint Francis Tapestries David Roche Collection to September 2

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout