Weaponising myths of the Vietnam War

Vietnam veterans were branded ‘baby killers’ by the Australian public. A new book takes a fresh look at the stories we tell ourselves about a difficult war.

Everybody knows that when troops returned home from the war in Vietnam they were greeted by demonstrations at the airport, where they were spat upon by women and branded “baby killers”.

Like many things that everybody knows, this isn’t true.

Everybody knows the freshly returned veterans were human timebombs, irreparably damaged by the terrible things they had seen and done in the jungles of Southeast Asia, unable to readjust to civilian life and apt to explode into homicidal rages at the pop of an exhaust.

Because it stands to reason, doesn’t it? Waging war wounds the warrior. A rifle (or a herbicide sprayer) has a victim at both ends. If we can all agree on that, then surely we will never again go to war.

Unless it’s, like, absolutely necessary.

In The Cult of the Victim-Veteran, author Jerry Lembcke argues that cultural constructs about aggressive protesters and rogue veterans have been used to justify, rather than condemn, America’s post-Vietnam wars.

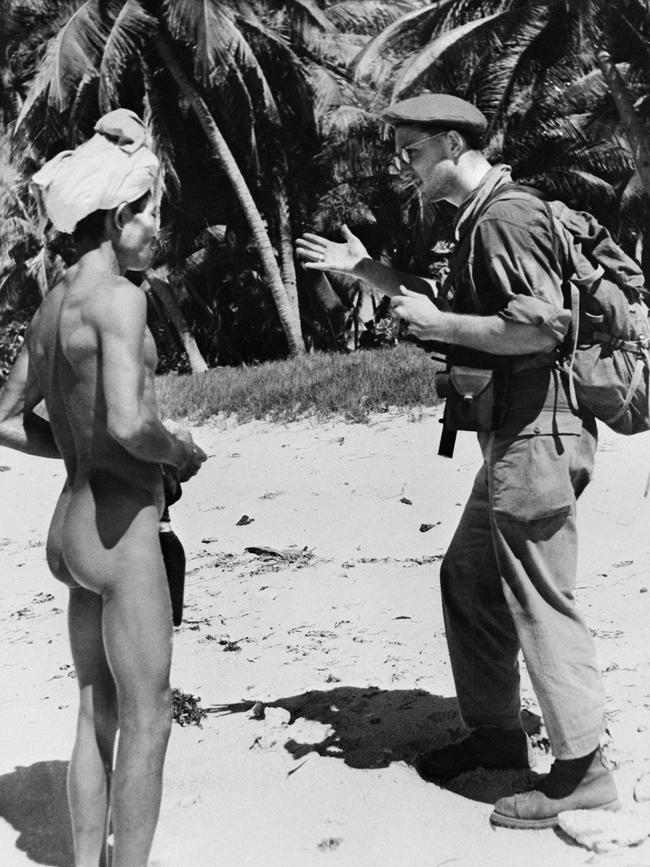

Lembcke is a sociologist who was drafted into the US Army in 1968 and served as a chaplain’s assistant – essentially the padre’s arms bearer, gofer and jeep driver – assigned to an artillery unit in Vietnam. On his return, he was active with Vietnam Veterans Against the War.

His previous works include The Spitting Image: Myth, Memory and the Legacy of Vietnam, in which he traces the myth of the spat-upon Vietnam veteran back to the slurring invective of the fictitious John Rambo in the 1982 Sylvester Stallone movie, First Blood, and the myth that there were airport demonstrations against returning soldiers back to a protest against the fictitious Captain Bob Hyde played by Bruce Dern in the 1978 Jane Fonda movie, Coming Home.

In his latest book, Lembcke argues that Hollywood movies “made Vietnam veterans into political props for slandering the anti-war movement”, and that the diagnosis of PTSD was formulated to pathologise dissident veterans (Look at those long-haired soldiers throwing away their medals! They must be mad!).

In Australia, there was no real movement of anti-war Vietnam veterans.

Almost all the protesters were civilians. Some Australian veterans have complained that they could not wear their uniforms in Australian streets for fear of being attacked by protesters, often women.

And it did happen, once, when 21-year-old Nadine Jensen, doused in red paint and kerosene, ran at the leaders of a welcome-home march in Sydney in 1966.

At the time, Jensen, a lone protester, was thought to be insignificant if not insane, but her actions later became seen as representative of the anti-war movement by some aggrieved veterans.

In the US – which had no Nadine Jensen – Lembcke compares a certain popular conception of the veterans’ experience to the ideas that justified the proto-fascist paramilitary Freikorps in Germany between the world wars. He writes: “To ground the idea that German soldiers had been betrayed on the home front, the German right promulgated three images … the idea of war veterans being abused when they returned home; the gendering of the betrayal narrative for an indictment of women and ‘the feminine’ in the culture; the use of Shellshock imagery as a metaphor for the German nation traumatised by the lost war and in need of rehabilitation through rearmament and the vindication that victory in another war would bring.”

Lembcke presents president George W. Bush’s declaration at the “end” of the Gulf War in 1991 that the US had finally “kicked the Vietnam syndrome” as evidence that “it was the loss of the last war that had revved the war machine for the new war”.

The defeat in Vietnam did not affect Australia in the same way as it did the US. When the last Australian infantry company withdrew in March 1972, it didn’t even look like a defeat: it was portrayed as a timely step in an orderly process of “Vietnamisation”.

But PTSD has been weaponised (to use the wrong word) in Australia in similar ways. When veterans’ psychological malaise is blamed on anti-war demonstrations as much as exposure to combat – as it is in Peter Yule’s 2020 work, The Long Shadow (“for many Vietnam veterans the rejection of their service has played as great a role as the trauma of war in their subsequent mental health struggles”) – protest against the war takes on the moral (and martial) equivalence of shooting at soldiers.

But that rejection of service can only have contributed to veterans’ PTSD if it actually happened.

If it did not happen, but the perception that it did nonetheless contributes to veterans’ PTSD, then the responsibility for that trauma must surely fall upon those who propagated the myths that veterans were spat upon and confronted by demonstrators at airports and so on.

When prime minister John Howard called upon protesters to “please vent your anger against me and towards the government” for the decision to invade Iraq in 2003, he was not actually calling for demonstrations against himself. He was suggesting there should be no protests at all – because look what protests did to the Vietnam veterans.

Lembcke has this to say about his own Vietnam experience: “Dehumanised by the war in Vietnam? Not me. I came home in February 1970 a better person for having been there … I had found my humanity in Vietnam and returned, like thousands of other veterans, with a commitment to help end the war.”

What does it mean when the subsequent actions of soldiers such as Lembcke (and perhaps 20,000 other members of VVAW) are held to have helped traumatise other veterans, and are used to delegitimise protests against more recent wars?

Who are the victim-veterans then?

Mark Dapin’s latest book is Carnage. He has written several military histories.

The Cult of the Victim-Veteran: MAGA Fantasies in Lost-war America

By Jerry Lembcke

Routledge, Nonfiction

130pp, $75.99

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout