This was meant to be the ‘official history’ of the Australian Signals Directorate … what happened?

A book commissioned at a cost of $2.2m was curtailed, costing taxpayers. What was the real problem?

John Blaxland and Clare Birgin’s “unofficial history” of Australian signals intelligence, set to be published on Monday by UNSW Press, has an intriguing history. For one thing, it started life as an “official history” of the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD), and it was originally due to be published by ANU Press.

The signals directorate is the Federal agency that gathers intelligence through signals interception. Much of its work is done in secret. In 2019, Professor Blaxland was commissioned by the ASD’s then director-general, Mike Burgess, to produce a two-volume history that would chart the progress of the ASD through its predecessor organisations to the present day. While the writing team would exercise editorial control, the ASD would have veto over security issues (a similar arrangement to that which Blaxland worked under while writing The Official History of ASIO).

In 2020, the ASD’s new director-general, Rachel Noble, reduced the remit of the project by 25 years, so the narrative would conclude in the mid-1990s. Having excised the closing section, the ASD then claimed to be affronted by the opening chapters, which placed the department’s methods in their historical context via a survey of cryptography and communications interception from ancient times to Federation.

Blaxland offered to reduce or remove the offending material, but it was already somehow too late. The ASD asked for its money back. The ANU agreed to refund only the unused portion. Blaxland and Birgin’s official history, commissioned at a cost of $2.2 million, was curtailed, at a cost to the Australian taxpayer of about $500,000.

Precisely nobody in the world believed that the ASD sought greater oversight of the project in order to conceal some top-secret success or hitherto unpublicised organisational virtue. Approximately the same number of people believed that former Signals troop commander Blaxland could not be trusted with matters of security.

So, what was the real problem?

Nobody who knows seems willing to tell.

Blaxland and Birgin eventually resolved to produce a historical survey of Australian signals intelligence generally, rather than the directorate specifically, with reference only to publicly available sources. The ANU backed away from publishing, presumably to avoid antagonising the ASD, with which the university is a partner in the Canberra Cyber Hub.

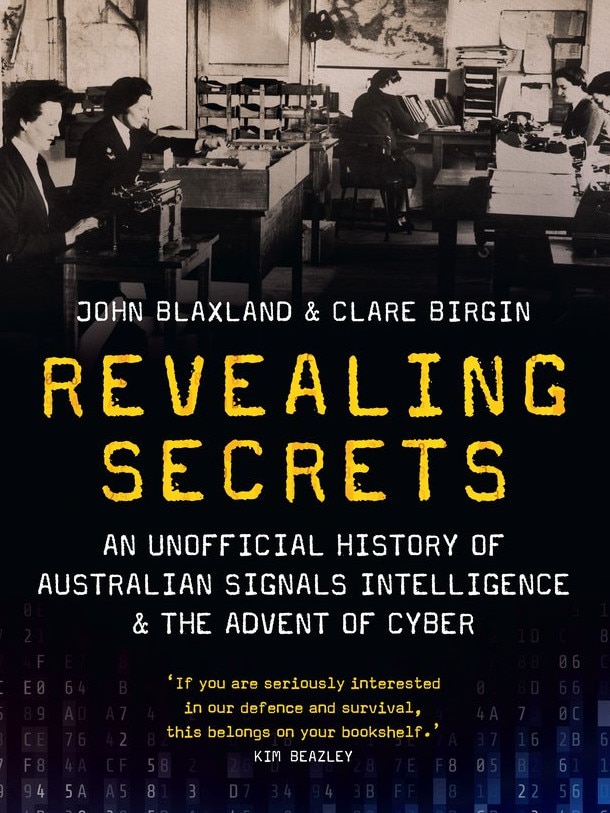

The full title of the book that has emerged from this intrigue is Revealing Secrets: An Unofficial History of Australian Signals Intelligence & the Advent of Cyber. It maintains the style, if not the imprimatur, of an official history, packed with facts and figures, charts and diagrams, and measured, unsensational judgements.

Blaxland’s work on ASIO was enlivened by the inclusion of interviews with former ASIO agents who had never had a public voice. Apparently, similar oral-history interviews were conducted with ASD operatives, but they had to be binned along with the rest of the data that had been gathered. So we do not discover if ASD officers of the recent past are worthy inheritors of the traditions of the field’s eccentric, sometimes brilliant local pioneers such as Florence McKenzie, a founder of the Australian Women’s Flying Corps at Sydney’s Feminist Club in 1938, who taught classes in Morse code for corpswomen and later established the Women’s Emergency Signalling Corps. We do not know if the directorate is staffed with classists such as Athanasius Pryor Treweek and Professor Arthur Dale Trendall, who served with an Army cipher-breaking unit formed at Victoria Barracks, Sydney, in January 1940. Trendall was an expert in 4th-century BC Greek vases, with an apparently intuitive approach to code-breaking. Treweek is described as “a polymath; highly gifted in mathematics and linguistics and with a photographic memory”, who in the 1930s “foresaw the value of learning Japanese.” A lecturer at Sydney University in ancient Greek, he was also a militia officer in the artillery, eventually rising to the rank of lieutenant colonel.

They don’t make them like that anymore. Or, if they do, we’re not allowed to know about them.

What we do know is that scandal intermittently disturbed public perceptions of the ASD in the 25-year period that was taken out of the scope of the official history. We know there were allegations that the department broke the law by passing on intercepted telecommunications between the captain of the MV Tampa and the Maritime Union of Australia in 2001.

We know that in 2002 a dossier of complaints by a group of six senior officers was leaked to The Daily Telegraph, alleging a culture of extramarital affairs (between spies who’d have thought it?), incompetence, nepotism, corruption and law-breaking. We know that in 2018 The Daily Telegraph reported a plan for the ASD to monitor emails, text messages and bank records of Australian citizens without a warrant.

Blaxland and Birgin, denied the use of official records, have no further light to shed on these matters of considerable public interest.

There’s some engrossing material in the book, but its novelty lies in the extent of its detail rather than any particular revelation – although I personally did not realise that many of the successes attributed to Coastwatchers were actually due to signals intelligence and miscredited to protect the integrity of their true source.

By far the most interesting period in the history of Australian signals intelligence is World War II, and the directorate was not founded until 1947, so Blaxland and Birgin’s best sections have little to do with the ASD.

Meanwhile, the first volume of the really-honestly-totally-official-this-time history of the ASD, John Fahey’s The Factory, was released in February, complete with the author’s insistence that he had been “left to write free of oversight or interference” except in questions of accuracy and national security.

Between them, the two studies offer a sturdy historical framework for any enterprising researcher – perhaps with the help of a whistleblower or two – to build a truly unofficial warts-and-all history of the directorate.

And I suspect that might be the lasting legacy of the ASD’s decision to sideline Blaxland’s original idea.

Mark Dapin is a journalist and military historian.