Theatre in the ancient world: what you didn’t know about the Roman empire

This remarkable exhibition deals with an aspect of Roman culture that is relatively unfamiliar to most people.

This remarkable exhibition deals with an aspect of Roman culture that is relatively unfamiliar to most people yet – as the proliferation of vast and ambitious stone theatres throughout the empire attests – was evidently considered important and worthy of generous state patronage. The exhibition brings together a great deal of material that many visitors and even scholars will never have seen before and is accompanied by a substantial catalogue that will be a valuable reference work for anyone concerned with the history of theatre.

The story begins in Greece with the origin of theatre in the cult of Dionysus, the god of intoxication, imagination and altered states of consciousness but also of life, death and rebirth. Theatrical performance seems, according to ancient sources, to have developed from choral songs in honour of the god, as one of the singers emerged from the chorus to impersonate a human or divine character. By the time of Aeschylus, plays were performed by two actors – who could take a variety of roles by changing masks and costumes – and a chorus, whose leader, the coryphaeus, also might function as a semi-character in dialogue with the actors. Sophocles added a third actor, making possible triangular relations between characters, as in the recognition scene at the climax of Oedipus Rex.

The mysterious, even mystical associations of dramatic illusion, with resonances of the most primitive forms of ritual performance, never entirely disappeared even in the rationalist climate of the so-called fifth-century BC enlightenment of classical Athens. Dionysus was worshipped not only in the public cult and in his great festival at Athens but also as the divinity of a mystery cult – of which the Orphic mysteries seem to have been a variation – that prefigured Christianity in offering salvation after death to its initiates, regardless of class or distinction between free and servile status.

This was a radical departure from the old Greek idea of the afterlife as a grey and dreary world of largely undifferentiated gloom for all, with a handful of notable exceptions. The contrast is staged in Aristophanes’s extraordinary comedy The Frogs – extraordinary among other things because Dionysus himself is brought on stage as a ludicrous protagonist who embarks on a journey to the underworld and ends up, after making his way with his slave Xanthias through grim darkness and rivers of sewage, hiding behind a bush spying on a procession of the blessed, singing and dancing in the mystical radiance of illumination in his own mysteries.

One of the most striking things about Greek theatre is its clear generic distinction, from the beginning, between tragedy and comedy. In other traditions of performance humour and pathos, epic struggles and clowning, alternate unexpectedly; in Greek theatre they are kept distinct, and this determines not only the storyline and action but also sentiment, tone and register of language. Thus in tragedy there will never be a hint of obscenity or ribaldry; but in comedy obscenity, scatology and invective are not only permitted but clearly felt to be essential to the genre. At the beginning of The Frogs, again, Aristophanes brilliantly manages to deplore the baseness and predictability of scatological humour while still incorporating the vulgar slapstick his audience would have expected.

Yet there was an intermediate genre, of which very few playtexts survive, known as the satyr play. These were presented as a kind of light relief after a trilogy of tragedies; unlike comedy, they dealt with tragic subject matter but in a burlesque spirit, and their chorus was composed of satyrs.

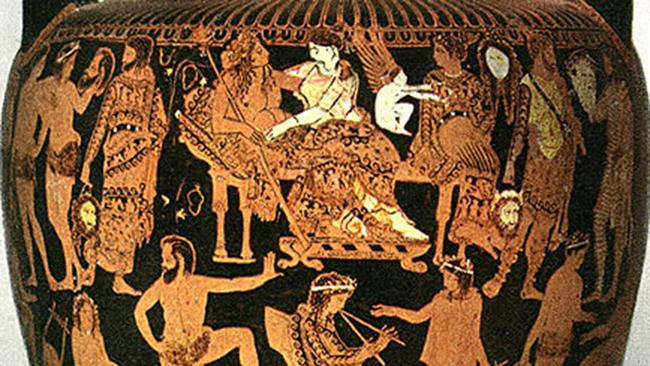

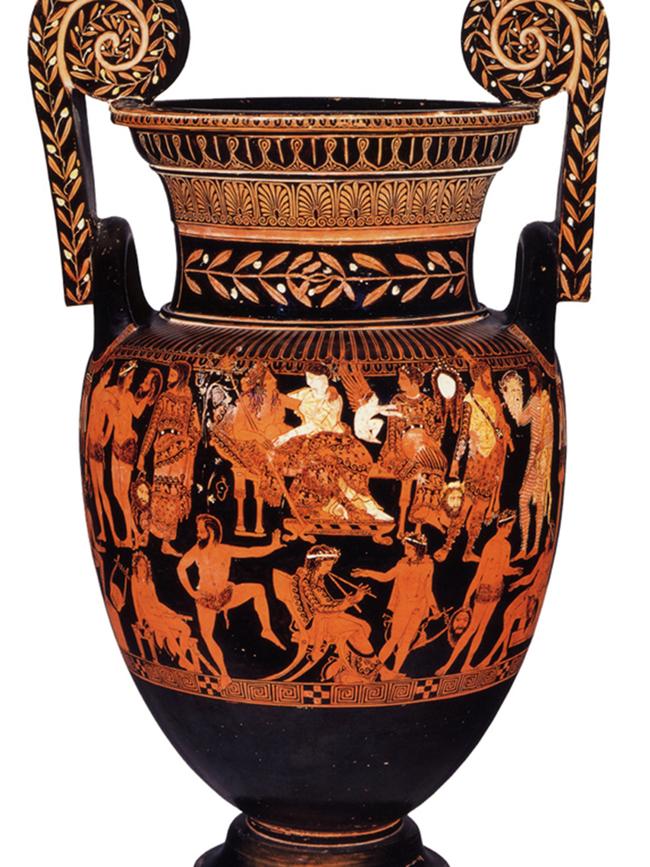

Many Greek vases, including some in the Nicholson Collection in Sydney, represent actors and performance, but the most remarkable of all, the Pronomos vase, usually in Naples but lent for this exhibition, preserves a wealth of images of the cast of a satyr play.

Pronomos was a celebrated aulos (flute) player in the fourth century BC. He is shown with the lyre player, in one section of the vase; in another we see the two main actors, men of around the middle age, in costume as Heracles and Papposilenos, leader of the satyrs, and holding their masks. Much of the body of the vase is decorated with images of the younger and still beardless youths who will perform the satyr chorus: they are wearing their satyr loincloths with phalluses, and are mostly holding the bearded masks they will wear for the performance; one has put on his mask and is practising his dance steps.

Another feature of Greek drama in its golden age in the fifth century BC is that new plays were written every year and submitted for production at the great theatre festivals, of which the most important was the festival of Dionysus, held in Athens early in spring. Only three tragic authors could be produced each year, so even to be shortlisted as one of the three was an honour; to take first prize in the contest was a great achievement both for the playwright and his producer. Plays could be performed in other festivals, and we know Aeschylus took some of his plays to Sicily, where he died at Gela. But repertory theatre in the modern sense did not arise until after the great age of original composition had come to an end, in the fourth century BC and the Hellenistic age.

This is the period when Rome became a significant power first in Italy, then the Mediterranean, and ultimately came to dominate Greece itself as well as the Hellenised Near East. Although the Romans were sometimes suspicious of Greek values, they could not fail to understand that the Greeks were vastly more sophisticated in all areas of culture, and the history of Latin literature is largely one of borrowing and adapting from Greek literary and philosophical sources. This process of assimilation was obviously helped by the fact the whole southern part of the peninsula was occupied by Greek cities that were as old as Rome itself and considerably more sophisticated; thus Virgil moved from Rome to Greek-speaking Naples to write the Georgics and the Aeneid, the national epic of Rome.

Educated Romans, especially no doubt of the senatorial class who held the highest administrative, legal and military offices, were bilingual from quite an early date, since Greek was the language spoken in much of Italy itself and especially after their city came to rule the Greek-speaking east. They must have seen theatre in the Greek south long before it was produced in Rome itself or even written in Latin. As we learn from the exhibition, it was largely bilingual authors with a Greek background who composed the first dramas in Latin.

But drama itself had changed with evolutions in social structures; Greek tragedy had arisen in the moral environment of the ancient polis with its strong sense of individual responsibility and agency, and moral situations simply did not have the same urgency when citizens had become, as today, largely passive members of enormous and impersonal states. At the same time the acerbic and polemical comedy of that period had given way to the more innocuous comedy of manners written by authors such as Menander.

Nonetheless tragedy seems to have enjoyed considerable success in third century BC Rome – the period of the Punic Wars that turned Rome into a great power – mainly in Latin adaptations written, as already mentioned, by authors of Greek extraction, such as Livius Andronicus and Naevius.

Comedy inspired by Menander seemed to have a more durable success in Rome, with authors such as Plautus and Terence. But perhaps above all the cultural environment of Rome was very different from that of Athens, in which all classes attended the festival of Dionysus, and in which the democratic government funded the poorer citizens to allow them to attend an occasion that was considered socially and culturally significant. Culture in Rome was far more divided between educated patricians and the uneducated masses than could be imagined in Greece.

So the Roman public was always more likely to enjoy grosser forms of comedy and slapstick. As it happens, there were several sub-literary theatrical traditions even in the Greek south for Latin authors or even showmen to draw on. One was a popular, perhaps pre-Greek tradition in Campania, known as Maccus, in which characters wore grotesque masks, several of which are represented in the exhibition.

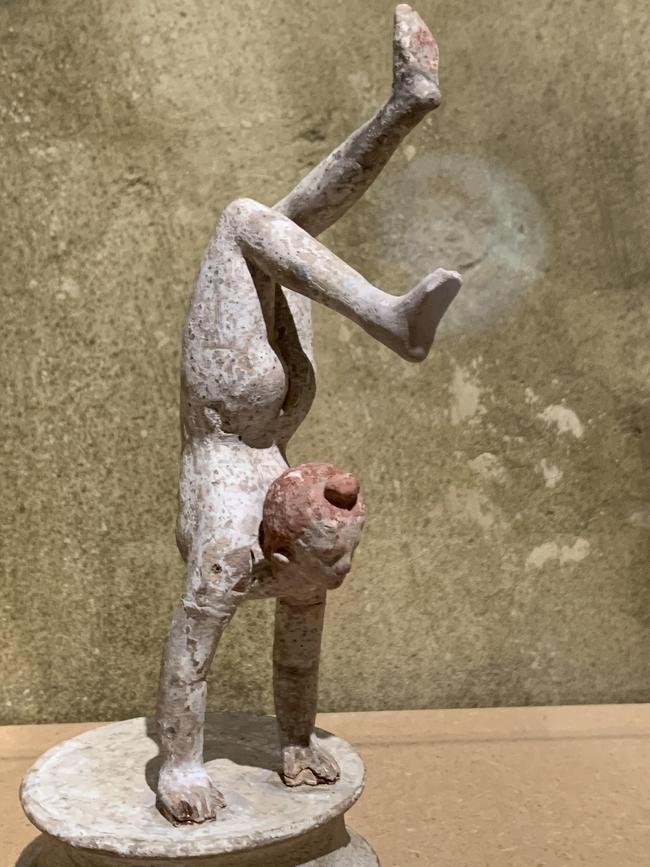

Other Greek popular forms of theatre included pantomimes, in which masked but silent actors presented mimed and danced versions of mythical subjects narrated by a chorus, and mimes, which were unmasked musical farces that included female performers. Such performances often included acrobatics and nudity, and the exhibition includes a couple of beautiful terracotta statuettes of naked girls doing handstands.

The Roman state invented mass entertainment as a form of social control, as is well-known from the example of the bloody games, with their slaughter of wild animals and gladiatorial combats, that were put on in the great arenas such as the Colosseum.

It is depressing to see how the Greek theatre of Taormina in Sicily was debased for Roman mass spectacles by removing the front rows of seats to keep the audience safe from the violence taking place below. But it seems from this exhibition that even more harmless forms of mime, slapstick and burlesque, enormously popular with audiences, were considered useful instruments of social management by the state; otherwise it would not, again, have invested very large amounts of money in building massive stone theatres with enormous capacities.

An interactive map in the exhibition allows us to see the proliferation of such theatres around the empire and to click on individual ones for more information. Architectural models, too, help us to understand the structure of these buildings, including their distinctively Roman permanent stage settings. They were not only erected in places where theatre had a long tradition but in new cities that the Romans seem to have built as a demonstration of the advantages and pleasures that the empire could offer – as in Timgad in Algeria, which had a theatre as well as baths and fountains, all of which would have been new to the native Berbers.

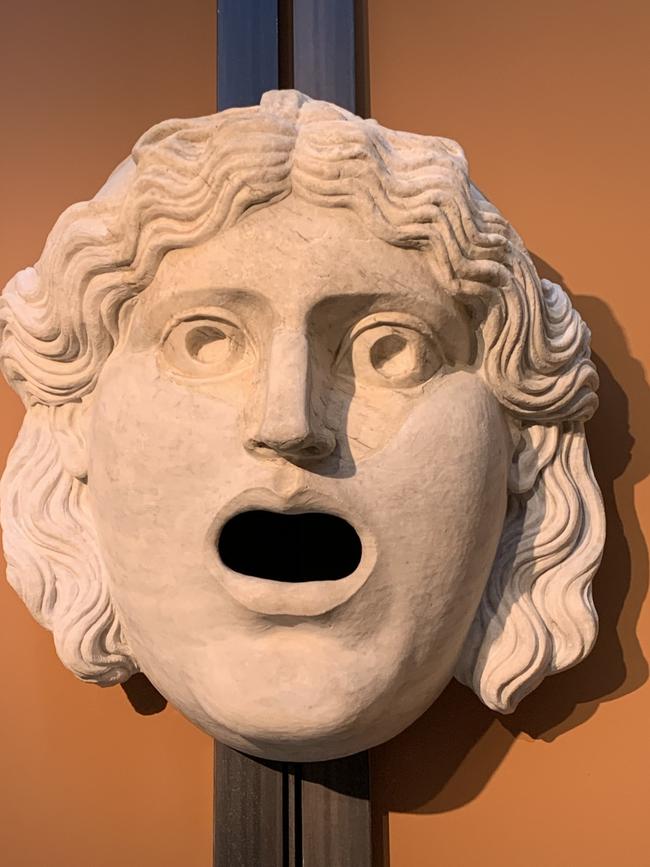

In Rome itself there were several important theatres, including the Theatre of Pompey, where Caesar was murdered, and that of Marcellus, built by Augustus. From this edifice, largely still intact, there is an impressive display of colossal marble reproductions of masks representing different character types from New Comedy such as the “reckless young man” and the “false virgin”.

We can see a direct connection between these types – as well as Plautus’s clever slave, the origin of a long tradition that leads to Figaro and Jeeves – and the modern comedy of Moliere in the 17th century, even as the great French comic author also draws on the more popular traditions such as commedia dell’arte that have their roots in ancient mimes and pantomimes.

Theatre in the Roman World

Ara Pacis Museum, Rome, to November 3

Theatre in the Roman World

Ara Pacis Museum, Rome, to November 3

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout