‘Extraordinary’ exhibition from Ancient Greece in Canberra

A National Museum of Australia exhibition of ancient Greece artefacts reveals the rich history of civilisation.

At the heart of the unique dynamism, curiosity and sense of freedom that the modern west inherited from antiquity was the Greek belief in the value of contest and competition. In his didactic poem Works and Days (c. 700 BC) Homer’s contemporary Hesiod speaks of the difference between good and bad Eris, or strife – the same goddess, or personification, who throws the golden apple of discord into the wedding of Peleus and Thetis, leading to the Judgement of Paris and the Trojan War.

Bad strife incites us to war, while good strife inspires our striving to be better and to excel others. Thus, as Hesiod memorably writes, “potter is angry with potter and carpenter with carpenter; beggar begrudges beggar, and poet envies poet”. A few years ago, in the formerly Greek city of Bari in Apulia, I walked through a street lined with old women making orechiette pasta on tables outside their houses. I stopped to talk to one who told me that her orechiette were the best, and that the other women hated her because the prince always sent his driver to buy pasta from her.

Everything in Greek culture, as this exhibition reminds us, had an agonistic aspect: there were poetry and music contests, and all dramatic festivals, like the Festival of Dionysus in Athens and others, were set up as competitions. Even political life had a fundamental dimension of contest in the arguments between rival speakers that go back to Homer and anticipate the character of later democracy.

The most famous of ancient contests today are the Panhellenic sporting festivals, especially the Olympic Games held in honour of Zeus on the west coast of the Peloponnese. These games, as well as the Nemean, Isthmian and Panathenaic ones, were so important that war – bad strife – was suspended and truces declared to ensure the safe passage of competitors and spectators.

Athletic training was an important part of Greek education, especially for the wealthier classes. Education was divided into three parts; the most elementary was learning to read and write and count, skills necessary for any shopkeeper, merchant or small businessman. The other two parts were “music” which in effect meant music and literature, and athletics. These were less commonly studied in families of modest means, who could not afford to let their sons take so much time off from their duties on the farm or in the workshop.

Physical training had a practical application in the Greek city-state, which was the basis of Greek culture, fostering even before the rise of democracy a culture of self-reliance, communal responsibility and independence. The free citizens of the polis were also its army; if war broke out or was decided upon, it was the citizens themselves who would fight. There was universal military training from about the age of 18 to 20, and in Athens, men were liable for call-up from 21 to 60.

It was thus every citizen’s civic duty to keep himself in good physical condition, and the gymnasium and palaestra were important parts of all Greek cities, even into the Hellenistic period. Greek medicine was also far more concerned than our own with keeping the body healthy in the first place, with a combination of diet and exercise. And it seems to have been generally effective; while early modern literature regularly characterises doctors as quacks and butchers, ancient Greek authors assume that doctors really can help you to be well.

But the culture of athletic competition extended far beyond practical benefits like training strong bodies for the defence of the state. It was the origin of the uniquely original Greek idea that the body could be beautiful; as I have observed before, this is something much more complex than the universal sexual response to other bodies, which operates on a scale from desire to repulsion, even if images of bodies will always retain the potential to evoke simpler erotic reactions. Beauty is nonetheless fundamentally different, inherently more disinterested: the Archaic Kouros statues of naked youths are not primarily about desire but evoke an image of poise and harmony, which is the physical image and manifestation of a deeper moral harmony. They are embodiments of the assumptions that we call humanism: confidence in our own ability to think and act for ourselves, not simply to believe the witch-doctor or obey the tyrant. This is the kind of confidence that produced both democracy and philosophy.

But although these statues are still and harmonious, they arise out of an experience of intense excitement, of struggle and triumph in the games. Greek has a unique word for beauty-in-victory, kallinikos, and a whole genre of poetry arose to celebrate the splendour of the triumphant athlete. We can still read many of the magnificent epinician poems of Pindar, whose verse, as Horace later says, has the awe-inspiring majesty of a mountain-torrent crashing over rocks.

But Pindar knew that the moment of victory is as brief as it is brilliant, and the sporting contests themselves are hardly more than glanced at in poems that combine mythology, praise for the victorious city and an evocation of its history, as well as moral advice. His poems too, while evoking the turbulence and excitement of the contest, end in stillness, as he describes the eagle of Zeus relaxing its wings, soothed by the golden lyre of Apollo, which he addresses in Pythian I:

and Zeus’ eagle sleeps upon his perch, releasing his swift wings by his sides,

– lord of birds – and you pour a dark cloud over his beaked head,

a sweet closing of the eyes; and as he sleeps

he lifts his smooth back, taken by your rhythms.

This extraordinary passage seems almost echoed in a Hellenistic coin from Elis, of which the sanctuary at Olympia was a dependency, with a head of Zeus on the obverse and a seated eagle on the reverse. The calm of the athlete after victory is evoked in a copy of the lost Diadoumenos by Praxiteles, as the young man binds the red fillet of victory around his head.

And as we see from a passage quoted in the catalogue (p. 63), the idea of beauty evoked by such statues came to shape and articulate the experience of real bodies in turn – life, as Oscar Wilde said, imitating art – when Socrates describes a young man entering a room as being beautiful as a statue (Plato, Charmides, 154).

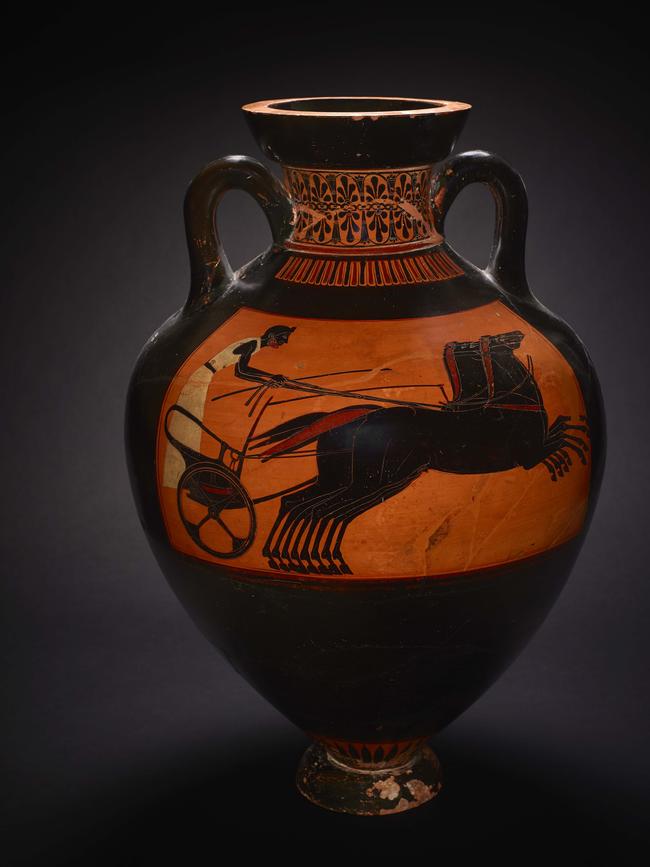

Although there are some fine examples of sculpture in this exhibition, these are inevitably mostly later ancient copies of lost originals, and there is no doubt that the most important pieces are the painted Attic ceramics, all of which are original and unique works. Among these are several fine Panathenaic prize vases, each illustrating the sport for which it was awarded and once filled with 45 litres of the finest olive oil from the sacred grove of the goddess Athena. The vases themselves were durable tokens of honour and were sometimes buried with their owners or dedicated in temples. Among the examples here are one of a charioteer (c. 520 BC) – the sport of kings and the very rich in ancient times because of the cost involved – standing in his light racing chariot and leaning forward in just the way we see again almost two centuries later in a vivid fragment from the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus (c. 350 BC). Charioteers were the only athletes to compete dressed in a long chiton, as we see also in the famous Charioteer of Delphi (not in this exhibition) or the more recently discovered Charioteer of Motya.

Other athletes were naked, as we see on another prize amphora decorated with two boys in a bareback horse race. The Greeks took pride in the fact that they competed naked, fully accepting the body that was surrounded by taboos in civilisations of the East. Indeed Thucydides speaks of the acceptance of nakedness as a relatively new but symbolically significant event in Greece itself. Certainly it is among the characteristic features of Greek civilisation that were fully developed by the date of this vase, which coincides with the first of two unsuccessful attempts by the Persian Empire to conquer Greece.

Other vases, although often subsequently found in burials, were originally made for use by the living, and played a prominent role in the most important form of private sociability in Ancient Greece, the dinner party or “symposium”. Ostentatious displays of wealth were considered vulgar in the classical period, so dining rooms were simply decorated, and the beautiful painted vases used as containers for water and wine, as well as bowls for mixing (the krater), jugs for serving and cups for drinking, must have been the main form of visual decoration. They were certainly valued as aesthetic objects and many were signed by their makers.

These ceramic pieces were often decorated with scenes of contest or conflict, often from the stories of the heroes or from the Homeric epics, but also, as we see here, with images of athletes at training, or of actors in costume or in one case a bard, like Pindar and of the same period, stepping up onto a dais to perform in a competition of rhapsodes.

The stories of Heracles were particularly popular, and all of his celebrated labours can be found illustrated on numerous vessels. The first of these was the slaying of the Nemean lion, whose skin afterwards served as a kind of mantle as well as his most consistent iconographic attribute. On one beautiful vase (c. 520-10 BC), the hero is shown on the shoulder suffocating the lion and again below in the main scene, reclining on a couch as though at symposium, with the skin hung on the wall behind.

Another amphora from around the same period illustrates the comical scene when Heracles returns to Eurystheus, who had ordered the labours, carrying the Erymanthean Boar alive, as had been stipulated. The cowardly king, terrified, leaps into one of the giant storage jar or pithoi which, as we can see, were set into the ground up to their shoulders. There are many other fine Attic ceramics, the best of them from the late 6th and 5th centuries, but the one that particularly stands out is an elegant amphora signed by Exekias (c. 540-30 BC). The design is strikingly open and uncrowded, with no distractions from the drama of the two central figures: Achilles fighting the Amazon queen Penthesilea, as recounted not by Homer but in the now lost and slightly later Aethiopis. According to legend, at the very moment that Achilles killed Penthesilea their eyes met and they fell in love. The helmet that Achilles wears, very similar to one displayed nearby, conceals all of his face except for the single bright eye that is the focus of the narrative and of the tragedy.

Story of the Moving Image

Australian Centre for the Moving Image

New permanent exhibition

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout