The tragic story behind the couple who took the birds of Australia to the world

Birds of Australia and Mammals of Australia remain among the most important books ever published on Australian wildlife, almost two centuries after they first appeared. But the remarkable Elizabeth Gould did not get to see them in their entirety.

Elizabeth Gould was born Elizabeth Coxen at Ramsgate, a blustery English seaside town, during the reign of King George III and Queen Charlotte. Hers was an old Kent family who, for generations, had provided officers for both the navy and the infantry.

By her early 20s, she had grown into an elegant young woman with a long, thin face, large, sad, dark eyes and chestnut hair.

Most of Elizabeth’s siblings had died young, but she had two energetic brothers: Stephen and Charles who, in time, would become prominent Australian graziers – Stephen in the Upper Hunter Valley of New South Wales and Charles further north on the Darling Downs of what is now Queensland.

Like many middle-class young women of the time, she found work as a governess, caring for a young relative of the eminent lawyer William Rothery at his palatial home near Buckingham Palace.

While working in London, she met John Gould, a prosperous, hard-driving young man who was running a business providing stuffed birds and animals, which were must-have accessories for the parlours and drawing rooms of the well-to-do, including the King of England.

While Gould made drawings of birds he collected, he soon discovered that Elizabeth was a much better artist than him. He thought they could not only build a family together, but a business publishing lavishly illustrated books.

The couple were married on a bitterly cold winter’s day in Piccadilly in 1829, and Gould soon had Elizabeth working overtime on their first bold publishing venture, making hundreds of illustrations in between multiple pregnancies (their first child died a few days after being born; she would lose another before they set sail for Australia).

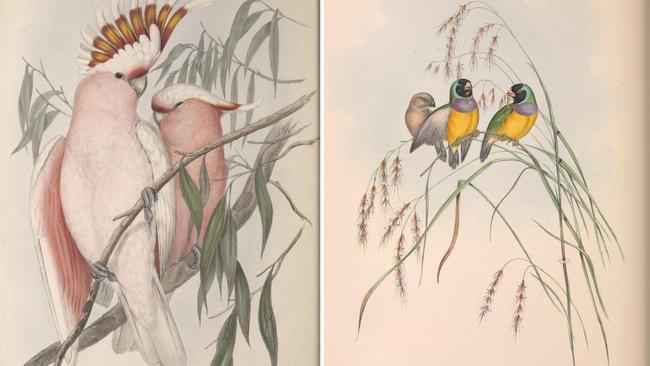

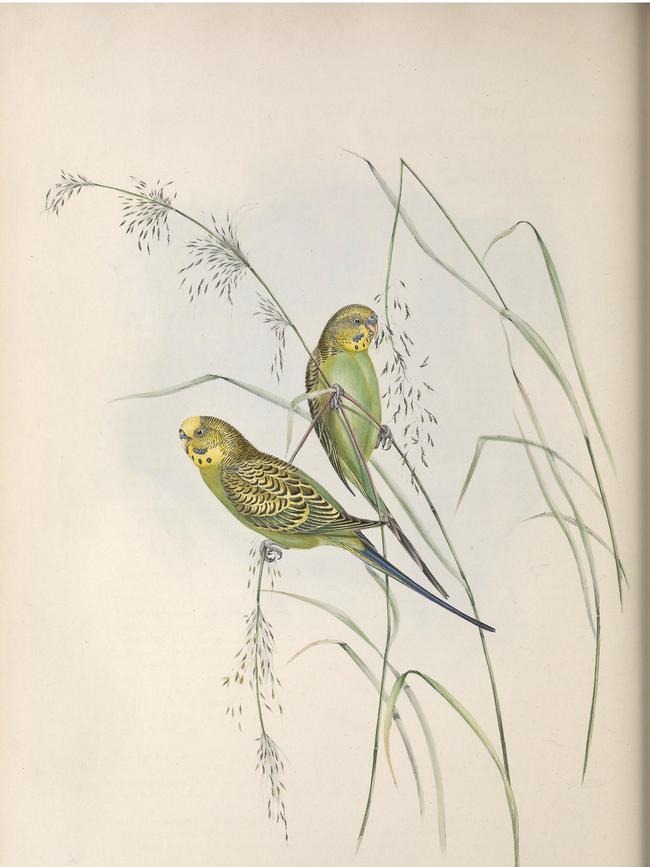

Elizabeth had soon earned a reputation as a brilliant illustrator, her subtle brush strokes capturing the vivid colours of budgerigars, cockatoos, lyrebirds, Himalayan pheasants, toucans and trogons with the gentle ruffle of their feathers, and the glint in their eyes.

In keeping with society’s views of the time, she had to share credit for her illustrations with her husband and it was his name which appeared on the front of their “luxury picture books” but Richard Bowdler Sharpe, who became the director of the bird displays at the British Museum, said Elizabeth was “due much of the ultimate success of her husband’s career, for she was as accomplished an artist as she was one of the best of wives”.

After a decade of marriage the Goulds had decided to produce the definitive series of books on Australian birdlife, introducing the world to species from the bottom of the world.

Elizabeth would have to leave her three youngest children in the care of her mother and cousin, and as the weeks ticked down to the couple’s departure by ship, she became highly stressed, with a “sudden & severe indisposition ... which inducing the utmost fears for her safety, rendered it very doubtful up to the last moment whether they would be able to go or not.”

She did, though, and became pregnant again on the voyage.

Anxious over the children left behind, she ached to return to London but from Hobart Town, she wrote to her mother asking her not to worry.

“John is so enthusiastic,” she said, “that one cannot be with him without catching some of his zeal in the cause.”

While John Gould journeyed into the wilds of Van Diemen’s Land and New South Wales looking for wildlife for his wife to draw, Elizabeth stayed at Government House in Hobart Town with Governor and Lady Franklin. Gould returned for a few days to be with his wife in May 1839, as she delivered the child conceived on the ship, the couple’s only Australian-born son, Franklin Tasman Gould, named for their hosts and surrounds.

Little Frank was four months old when his mother and father boarded a ship for Sydney, before travelling by a smaller vessel to Maitland, then swaying and rolling upon a bullock cart until they arrived at the Scone sheep and cattle property of Elizabeth’s brother Stephen.

Gould left his wife holding the baby and went off with two Indigenous guides to forage through the undergrowth of the Liverpool Range near modern day Muswellbrook looking for lyrebirds.

In the ramshackle bush homestead of her widowed brother, Elizabeth, lonely and constantly working, wrote to her mother to say that “Baby has been poorly but has recovered; he is seven months old today and has five teeth and is very fond of toddling about the room with a handkerchief round his waist … I do, my dear Mother, so very much long to see you. How are the dear children? Franklin is a bad feeder and lives more upon me than any child I have had before, but it does not hurt me as I am much healthier here than in England – the climate agrees with me well.”

After two years in the colonies, the Goulds returned to London to begin the enormous task of publishing seven volumes of the Birds of Australia.

With 37-year-old Elizabeth set to deliver their eighth child, they rented a holiday home beside the Thames at Egham in Surrey. On 10 August 1841, she delivered a little girl named Sarah, who would live a long and happy life of 85 years.

But the days after her birth were horrific for Elizabeth, who became feverish, shaking violently with savage chills. Despite the efforts of Gould and Elizabeth’s mother and doctor to cool her sweats, her temperature soared.

As little Sarah cried to be fed, her mother’s face became a mask of fear, confusion and anguish.

Elizabeth died in agony at the rented holiday cottage, just five days after she had given birth.

There were rumours that she – having borne eight children, while producing 500 lithographic plates and more than 1000 drawings for her husband – had succumbed to her work load.

But hard work had never troubled Elizabeth. She had succumbed, instead, to the curse of childbirth before the advent of antibacterial medications: an infection in the uterus.

A newspaper in London, reporting her death, said Elizabeth’s illustrations were “remarkable for beauty of execution and fidelity of design; and her premature death must be accounted a heavy loss to ornithological science”.

Gould never really got over Elizabeth’s passing. He was just 37 at the time, but he never remarried, never really sought another female companion, instead devoting himself to his birds and to keeping his children in the lifestyle to which they had become accustomed.

Though Elizabeth did not live to see them in their entirety, the books she and Gould envisioned, Birds of Australia and subsequent Mammals of Australia, were published in sections over the next two decades. They remain among the most important books ever published on Australian wildlife, almost two centuries after they first appeared.

The delightful Gouldian finch was named by John for Elizabeth, “who assisted me so zealously and with such talent in my ornithological pursuits … (and) who in addition to being a most affectionate wife, laboured so hard and so zealously.”

This is an edited extract from Mr & Mrs Gould by Grantlee Kieza (ABC Books), out now.